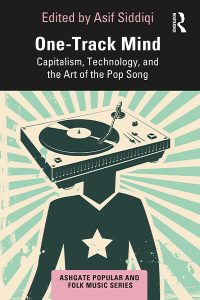

In One-Track Mind: Capitalism, Technology, and the Art of the Pop Song, Fordham history professor Asif Siddiqi, Ph.D., and 15 other writers attempt to answer those questions. They each delve into the history of a song from the past 60-plus years, and their essays, Siddiqi writes, “show the undiminished power of the pop song.” He sees them as “distillations of important flashpoints,” and he hears in them “ghostly echoes that persist undiminished but transform[ed] for succeeding generations.”

The idea for the book blossomed at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus in June 2019. That’s when the University’s O’Connell Initiative on the Global History of Capitalism provided funding for a workshop where Siddiqi and other contributors began to flesh out the cultural reflections they noticed in pop songs across the decades.

“We knew that there were a couple of running themes,” said Siddiqi, the book’s editor. “One was that technology was everywhere, not only in terms of recording studios [and instruments] but also media, like CDs and streaming, etc. And the other thing that was everywhere was, of course, capitalism, because of the business of making music.”

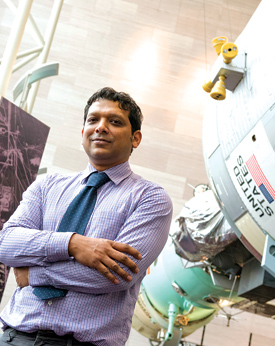

Siddiqi, a former Guggenheim Fellow, is best known for his books on the history of space exploration, including The Red Rockets’ Glare: Spaceflight and the Russian Imagination, 1857–1957. But he is also a guitar player and music lover with a keen interest in the technology of music production.

He said he was wary of gravitating too far toward the kind of classic rock often seen as the canon by fans and critics, so he encouraged contributors to highlight a diversity of artists and sounds. Their selections run the gamut from Afropop to hip-hop and span nearly five decades, from “Indépendance Cha Cha,” the 1960 Congolese anthem by Le Grand Kallé and African Jazz, to M.I.A.’s 2007 hit, “Paper Planes.”

Along with Siddiqi, four other Fordham professors or graduates wrote essays for the book, which was published last fall as part of Routledge’s Ashgate Popular and Folk Music Series.

“Immigrant Song” by Led Zeppelin

Esther Liberman Cuenca, Ph.D., GSAS ’19, a medieval historian, wrote about Led Zeppelin’s obsession with medievalism, evident in the J.R.R. Tolkien references and Viking allusions in their lyrics—the latter most prominent in 1970’s “Immigrant Song.” With its hard-charging riff and wordless, wailing chorus, the song “made an ideal conduit through which ideas about the medieval world of the Vikings were communicated in popular culture,” Liberman Cuenca writes.

Inspired by a triumphant stop the band made in Iceland on their way to the Bath Festival in England, the swaggering machismo of the track was in part simple braggadocio about their “conquest” of foreign music markets, but Liberman Cuenca notes that there may have been a bit of British tongue-in-cheek humor in the band’s nod to colonization.

“Led Zeppelin’s particular brand of medievalism,” she writes, “banked on a type of nostalgia for an idyllic, rural Britain reflecting the postwar, post-industrial anxieties that many British youth in the 1960s and 1970s experienced. … For the British, the failed [Viking] colony of Vinland represented their fears of how carefully calibrated imperial projects could fail.”

“Rebel Rebel” by David Bowie

The capitalist spirit of the music industry—and its focus on reaching foreign markets—is on full display in Fordham English professor Glenn Hendler’s essay on David Bowie’s “Rebel Rebel,” from 1974.

While the best-known version of the song, from the album Diamond Dogs, is a fairly straightforward rock song, Bowie decided he wanted to incorporate the sounds of Latin music for the U.S. single. In the mid-1970s, though, with album-oriented rock—and its mostly white purveyors—dominating FM radio playlists, the prominence of castanets and congas in the U.S. single meant that it was relegated to the AM dial, where listeners would find almost all non-rock (and non-white) sounds. And while that version still managed to crack the Billboard Hot 100 chart, it was replaced by the U.K. version after several months.

“The marketing did not match the product,” Hendler writes, “at least not in a context in which rock was being starkly differentiated from soul music, R&B, dance music, and Latin music. The U.S. single of ‘Rebel Rebel’ largely fell between the cracks of race, culture, format, and genre. The shape of those cracks would define the U.S. music market for years to come.”

“Mmmbop” by Hanson

In 1997, two decades after David Bowie released two versions of “Rebel, Rebel,” a different kind of marketing decision—opening direct lines of communication to fans via fast-growing online spaces—helped the brothers in Hanson turn their hit song “Mmmbop” into a springboard for building a devoted following, which is explored in an essay by Louie Dean Valencia, Ph.D., GSAS ’16.

Through the band’s official website and other online forums, Hanson’s fan engagement allowed the group to survive, Valencia writes. “The boy band singing about the ephemerality of relationships used digital technology to maintain their relationships with their fans—attempting to adapt to the digital era in real time.”

“Candle in the Wind 1997” by Elton John

Elton John released “Candle in the Wind 1997,” a tribute to the late Princess Diana, in September 1997, two weeks after her death. It’s an update to the 1974 version written in honor of Marilyn Monroe. In One-Track Mind,

Christine Caccipuoti, FCLC ’06, GSAS ’08, describes how the song—a massive hit and cultural phenomenon that John has protected from widespread commercial usage—tapped into the same shifting modes of consumption as Hanson’s hit “Mmmbop” did that year.

“As the still-nascent internet became a site for growing personal expression in the late 1990s,” Caccipuoti writes, “many chose to create memorial websites. … These mostly female-run sites included many of the same features: photographs of Diana, writing about the host’s personal grief, and the lyrics to ‘Candle in the Wind 1997.’”

“Paper Planes” by M.I.A.

In the book’s last chapter, Siddiqi tackles technology on the music-creation side—specifically the practice of digital sampling, which has shaped the sound of pop music in the past 30-plus years. He writes about M.I.A.’s “Paper Planes,” a 2007 song by a Sri Lankan–British artist that samples the Clash’s 1982 song “Straight to Hell”—itself a critique of British and American colonialism—to explore the hustles necessary to survive in the colonialized Global South.

As a cheap technology, sampling has both democratized music creation and, at times, led to more unlicensed co-opting of “global” music by established European and American artists, Siddiqi notes. But its predominant use in hip-hop points to a certain reclaiming of history.

“As with writers and historians who liberally quote from prior works, by analogy, hip-hop artists using the digital sampler invoke, echo, and cite earlier artists through mechanical reproduction,” he writes. “The digital sampler here is not simply a musical instrument, a technical artifact, it also becomes, as M.I.A. shows in ‘Paper Planes,’ a tool for writing and rewriting history for those for whom history has always been written by others.”

As a whole, One-Track Mind offers plenty of opportunities to see the way that pop songs contribute to the writing and rewriting of history.

“Every song has a life cycle from birth to out into the world,” Siddiqi said. “And to write that biography is actually to talk about a moment in time. So I think you can read these stories if you are just interested in social and cultural history. Even if you don’t know the song, it might tell you something.”

]]>

ASIF SIDDIQI

50 Years Ago, a Forgotten Mission Landed on Mars

Discover Magazine 12-1-21

“The Soviet space program was under a lot of pressure in the 1960s to achieve ‘firsts,’” says Asif Siddiqi, a Fordham University history professor who’s penned multiple books on the Soviet side of the space race.

CHERYL BADER

Rittenhouse Verdict Sparks Split Reactions, Fears of Vigilantism

Bloomberg.com 11-19-21

“I am afraid that as people are empowered by this verdict to weaponize the public spaces, we will see more fatalities,” said Cheryl Bader, a former assistant U.S. attorney and associate clinical professor at Fordham University School of Law.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT

‘I Want to Be a 21st-Century Trustbuster’: Zephyr Teachout on Her Run for A.G.

New York Magazine 11-24-21

Teachout is currently a professor at Fordham Law School, where she specializes in constitutional and antitrust law.

FORDHAM UNIVERSITY

Capital Campaign Watch: Dickinson, Fordham, Springfield, Tulane

Inside Higher Ed 11-22-21

Fordham University has announced a campaign to raise $350 million, probably by 2024. The university has raised $170 million so far.

Museum of American Finance to Present Virtual Panel on “SPACs: The New IPO?”

BusinessWire 11-30-21

“SPACs: The New IPO?” is sponsored by Citadel Securities and Vinson & Elkins. It is presented in partnership with the Fordham University Gabelli Center for Global Security Analysis.

Study Abroad Programs Reopen To Eager College Students

Gothamist.com 12-1-21

This fall, Fordham University only re-opened its London program. Joseph Rienti, director of the study abroad office, said the enrollment for that campus was higher than usual.

LAW SCHOOL FACULTY

CHERYL BADER

Rittenhouse Verdict Sparks Split Reactions, Fears of Vigilantism

Bloomberg.com 11-19-21

“I am afraid that as people are empowered by this verdict to weaponize the public spaces, we will see more fatalities,” said Cheryl Bader, a former assistant U.S. attorney and associate clinical professor at Fordham University School of Law.

JOHN PFAFF

In Depth Podcast: Why Kyle Rittenhouse was acquitted

Audacity.com 11-19-21

This week’s guests include Kim Belware, John Pfaff (sic), and Charles Coleman Jr.

… Pfaff (sic), an author and law professor at Fordham University, breaks down how self defense laws, open carry laws, and the burden of proof contributed to this case.

OLIVIER SYLVAIN

FTC Chair Khan Brings on AI Policy Advice From NYU Researchers

Bloomberg Law 11-19-21

They join Olivier Sylvain, a law professor from Fordham University, who is serving as Khan’s senior adviser on technology.

DORA GALACATOS

The future of geographic screens for NYC’s high schools is up in the air amid concerns over diversity, commutes

Chalkbeat.com 11-19-21

Dora Galacatos is the executive director of the Fordham Law School Feerick Center for Social Justice, which recently released a report calling for a number of reforms to make the admissions process more fair.

CHERYL BADER

Rittenhouse’s Winning Strategy Rested on Tear-Filled Testimony

Bloomberg Law 11-19-21

Cheryl Bader, a former federal prosecutor who now teaches at Fordham University School of Law, said there didn’t appear to be any obvious errors in the state’s case.

CHERYL BADER

Rittenhouse verdict raises stakes in Arbery trial

SFGATE 11-20-21

Cheryl Bader, a former assistant U.S. attorney and a professor at Fordham University School of Law, said that while people of any race can claim self-defense, implicit bias means that race will inevitably factor into who can successfully claim it.

RICHARD M. STEUER

The congressional debate over antitrust: It’s about time

The Hill 11-20-21

Richard M. Steuer is an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School

ERIC YOUNG

Who Was Watching Over The CEO Of Activision Blizzard?

Forbes 11-22-21

Eric Young, a former chief compliance officer at a number of large global investment banks, and currently an adjunct professor for compliance at Fordham Law School, said about this matter, “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.”

OLIVIER SYLVAIN

Hochul tops new poll

Politico 11-22-21

Olivier Sylvain will be senior adviser on technology to [FTC Chair Lina] Khan. He is a law professor at Fordham University and is considered a Section 230 expert.

CHERYL BADER

Table Topics: Oil Prices, Rittenhouse, and Ethical Debates

Player.fm 11-23-21

Cheryl Bader, clinical associate professor of law, Fordham

OLIVIER SYLVAIN

FTC Chair Lina M. Khan Announces New Appointments in Agency Leadership Positions

MyChesco.com 11-24-21

Olivier Sylvain will serve as Senior Advisor on Technology to the Chair. Sylvain joins the FTC from Fordham University where he has served as Professor of Law.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT

‘I Want to Be a 21st-Century Trustbuster’: Zephyr Teachout on Her Run for A.G.

NY Mag 11-24-21

Teachout is currently a professor at Fordham Law School, where she specializes in constitutional and antitrust law.

BRUCE GREEN

Jan. 6 panel faces double-edged sword with Alex Jones, Roger Stone

The Hill 11-26-21

“Even people that have a tendency to lie in a lot of different contexts have strong motivation not to lie under oath because it puts them at risk,” said Bruce Green, a law professor at Fordham University and a former federal prosecutor.

BRUCE GREEN

Ahmaud Arbery trial shines a light on prosecutorial misconduct

DNYUZ 11-30-21

Bruce A. Green is the Louis Stein Chair at Fordham Law School, where he directs the Louis Stein Center for Law and Ethics.

BRUCE GREEN

10 Things in Politics: Kamala Harris’ Big Tech problem

Business Insider (subscription) 12-1-21

Bruce Green, who leads the Louis Stein Center for Law and Ethics at Fordham Law School, said it would be “misleading or irresponsible” to make such a commitment.

JOEL COHEN

When a President Comments on a Pending Criminal Case

Law & Crime 12-1-21

He is the author of “Broken Scales: Reflections On Injustice” (ABA Publishing, 2017) and an adjunct professor at both Fordham and Cardozo Law Schools.

TANYA HERNANDEZ

A college law professor who teaches critical race theory worries that educators are living through another ‘Red Scare’

Business Insider 12-1-21

Tanya Katerí Hernández feels fortunate to be a tenured professor at Fordham University School of Law, a private Catholic institution in New York City that she said supports her teaching on critical race theory.

FORMER LAW SCHOOL FACULTY

ALISON NATHAN

Who Is Alison Nathan? Ghislaine Maxwell Trial Judge

Newsweek 11-29-21

From 2008 to 2009, she was a Fritz Alexander Fellow at New York University School of Law and before that, from 2006 to 2008, a visiting assistant professor of law at Fordham University Law School

ANNEMARIE MCAVOY

From Serious to Scurrilous, Some Jimmy Hoffa Theories

NewsNation USA 11-24-21

Former federal prosecutor and adjunct law professor at Fordham University Annemarie McAvoy discusses history and fascination of the Hoffa case.

GABELLI SCHOOL OF BUSINESS FACULTY

FRANK ZAMBERELLI

How does the Impact Index support sustainable fashion?

Sustainability.com 11-19-21

Frank Zambrelli, Executive Director of the Responsible Business Coalition at Fordham University’s Gabelli School of Business, says, ‘it is not a green light or a red light. It’s merely a platform. Nobody’s saying this is a better skirt than this one; we’re just saying, “This skirt was produced this way, with these certifications”’.

BARBARA PORCO

Companies Are Falling Short Measuring Environmental Performance Against Goals: Report

Forbes 12-2-21

As I wrote last month, “All elements of ESG reporting are really based on proper risk management,” according to Barbara Porco, director for the Center of Professional Accounting Practices at Fordham Business School.

LERZAN AKSOY

Aflac Lands Top-15 Spot on the 2021 American Innovation Index

PR Newswire 12-1-21

“The pandemic continues to challenge companies to adapt their business models at a faster rate than in normal times,” said Lerzan Aksoy, Ph.D., professor of marketing at Fordham University’s Gabelli School of Business.

GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SERVICES FACULTY

Aging Behind Prison Walls

WFUV-FM 11-30-21

Tina Maschi, PhD, LCSW, ACSW Professor, Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service

ARTS & SCIENCES FACULTY

BRYAN MASSINGALE

Christians must develop an anti-racist spirituality, Mennonite authors argue

National Catholic Reporter 11-24-21

Among that year’s honorees was Fr. Bryan Massingale, who was then on the faculty of Marquette University in Milwaukee and now teaches at Fordham University in New York.

JACK WAGNER

In Their 80s, and Living It Up (or Not)

New York Times 11-26-21

Dr. Katharine Esty has the right idea. I am 85 and my wife is 80. I work out six times a week at my local gym, and I teach mathematics at Fordham University. We are fully vaccinated, including boosters.

KATHRYN REKLIS

Telling Native stories on TV

The Christian Century 11-19-21

Kathryn Reklis teaches theology at Fordham University and is codirector of the Institute for Art, Religion and Social Justice.

SHELLAE VERSEY

Forever Young: Seniors Dance in the Bronx

The Villiage Voice 11-24-21

“Even before COVID, we were already noticing the squeeze of gentrification on the social lives of older adults who were living in these communities,” Shellae Versey, an assistant professor of psychology at Fordham University, tells the Voice in a phone interview, referring to members of racial minority groups being priced out of their neighborhoods.

CHARLES CAMOSY

Takeaways from the USCCB’s General Assembly

National Catholic Register 11-20-21

To help shed some light on the broader scope of what happened in Baltimore, and the general assembly’s true significance, the Register spoke with Charles Camosy, a moral theologian at Fordham University;

CHRISTINA GREER

Eric Adams, off on the right foot

Marietta Daily Journal 11-20-21

The rubber’s yet to hit the road and I’ve written plenty already about my doubts and concerns about Adams and what Fordham University political science professor and my FAQ.NYC co-host Christina Greer calls his “nervous cop energy.”

CHRISTINA GREER

Thanksgiving is upon us

Amsterdam News 11-25-21

Christina Greer, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Fordham University, the author of “Black Ethnics: Race, Immigration, and the Pursuit of the American Dream,” and the co-host of the podcast FAQ-NYC.

BRYAN MASSINGALE

Bryan Massingale wins social justice award from Paulist Center

The Christian Century 11-29-21

He currently teaches ethics at Fordham University, where he also serves as the senior ethics fellow for the school’s Center for Ethics Education.

ARISTOLTLE PAPANIKOLAOU

Jan. 6 panel faces double-edged sword with Alex Jones, Roger Stone

National Catholic Reporter 11-30-21

Looking ahead to the pope’s time in Cyprus and Greece, Aristotle Papanikolaou, co-director of the Orthodox Christian Studies Center at Fordham University, told NCR that “the symbolism is key.”

CHRIS RHOMBERG

Fattest Profits Since 1950 Debunk Wage-Inflation Story of CEOs

Daily Magazine 11-30-21

“Workers may be tired of seeing the fruits of their labor go to corporations making record-breaking earnings,” Chris Rhomberg, a professor of sociology at Fordham University, said at that point. “The Deere workers evidently felt that the company could afford more.”

SARIT KATTAN GRIBETZ

Yeshiva University Museum Receives NEH Planning Grant

Yeshiva University 11-20-21

Additional consultants on the project are Sarit Kattan Gribetz, Associate Professor of Classical Judaism at Fordham University, who has particular expertise on the Jewish calendar and its development during the rabbinic period and on aspects of the calendar as they relate to the historical experience of Jewish women;

ASIF SIDDIQI

50 Years Ago, a Forgotten Mission Landed on Mars

Discover Magazine 12-1-21

“The Soviet space program was under a lot of pressure in the 1960s to achieve ‘firsts,’” says Asif Siddiqi, a Fordham University history professor who’s penned multiple books on the Soviet side of the space race.

DAISY DECAMPO

The Ethics of Egg Freezing and Egg Sharing

The Cut (subscription) 12-1-21

Daisy Deomampo, a medical anthropologist and associate professor at Fordham University who has researched donor egg markets.

NICHOLAS JOHNSON

School Board Finds Anti-2A Bias In Elementary School Textbook

Bearing Arms 12-1-21

As Fordham professor Nicholas Johnson brilliantly pointed out in his book Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms, the Second Amendment has long played a role in advancing the cause of freedom in the United States.

CHRISTINA GREER

December is upon us

New York Amsterdam News 12-2-21

Christina Greer, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Fordham University, the author of “Black Ethnics: Race, Immigration, and the Pursuit of the American Dream,” and the co-host of the podcast FAQ-NYC.

FORMER ARTS & SCIENCES FACULTY

ROGER PANETTA

Houston highway project sparks debate over racial equity

MyNorthwest.com 11-23-21

Roger Panetta, a retired history professor at Fordham University in New York, said those opposing the I-45 project will have an uphill battle, as issues of racism and inequity have been so persistent in highway expansions that it “gets very difficult to dislodge.”

ATHLETICS

KYLE NEPTUNE

Early returns on the Kyle Neptune era at Fordham University positive

News12 New Jersey 11-19-21

The early returns on the Kyle Neptune era at Fordham University have been pretty positive.

Red Bulls Pick Up New Players In Super Draft

FirstTouchOnline.com 11-28-21

Janos Loebe, a German-born Fordham University product, will start to move from forward to attacking wingback, a key position on the field for New York.

ALUMNI

40 Under 40: Kyle Ciminelli, Ciminelli Real Estate Corp.

The Business Journals (subscription only) 11-19-21

[Kyle Ciminelli] Bachelor’s, finance, Fordham University; master’s, real estate and finance, New York University.

Devin Driscoll to Host Christmas Gathering

The Knoxville Focus 11-21-21

Devin Driscoll graduated from Catholic High School and went on to earn a degree from Fordham University.

Columnist Judith Bachman Captures The Spirit Of Sister Mary Eileen O’Brien, President Of Dominican College

Rockland County Business Journal 11-23-21

Sister O’Brien has dedicated herself to education for over 50 years. Sr. Mary Eileen earned a doctorate degree in Educational Administration and Supervision from Fordham University and holds a master’s degree in Adult and Higher Education from Teachers College of Columbia University and a master’s in Mathematics from Manhattan College.

Lacerta Therapeutics Appoints Min Wang, PhD, JD and Marc Wolff to its Board of Directors

BusinessWire 11-24-21

Dr. [Min] Wang received her PhD in Organic Chemistry from Brown University and a JD from Fordham University School of Law.

Teva Attorneys Leave Goodwin Procter For Greenberg Traurig

Law360.com (subscription) 11-24-21

He earned his law degree from Fordham University School of Law.

She went through foster care. Now she leads one of the oldest U.S. child welfare organizations.

MSNBC 11-29-21

[Kym Hardy] Watson, who holds degrees from Fordham University and Baruch College, CUNY, began her career in the 1980s after a summer job working with youth at St. Christopher’s Home.

FreedomCon 2021 – Native Lives Matter

Underground Railroad Education Center 11-27-21

[Loriv Quigly] earned her bachelor of arts in Journalism and Mass Communication from St. Bonaventure University, and a master of arts in Public Communication and Ph.D. in Language, Learning and Literacy from Fordham University.

The Hall case in the Poconos and malice in the US | Moving Mountains

Pocono Record 11-27-21

Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo holds a doctorate in Catholic Theology from Fordham University and authored a column on religion for the Washington Post from 2008-2012.

The Success Of Emmy Clarke, Both In And Out Of The Camera

The Washington Independent 11-29-21

[Emmy Clark] decided to attend Fordham University. She finished her studies in 2014 and received a bachelor’s degree in Communication and Media Studies.

Paraco’s CEO puts business lessons, family experiences in print

Westfair Communications Online (subscription) 11-19-21

…was born in Mount Vernon, the oldest of four sons He attended Fordham University, graduating in 1976 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in…

Greenberg Traurig Further Strengthens Pharmaceutical, Medical Device & Health Care Practice

PR Newswire 11-19-21

In addition, [Glenn] Kerner has experience in complex commercial litigation, antitrust, real estate litigation, and other civil litigation. He has a J.D. from Fordham University School of Law and a B.A. from Cornell University.

Three Universities Have Announced the Hiring of African Americans to Diversity Positions

The Journal of Blacks in Higher Ed 11-19-21

[Tiffany Smith] holds a master’s degree in education, specializing in counseling services, from Fordham University in New York.

President Biden nominates second out woman to federal appellate court

LGBTQ Nation 11-21-21

[Alison Nathan] has clerked in the Supreme Court and taught at Fordham Law School and NYU Law.

GOTS ramps up oversight on product claims in North America

HomeTextilesToday.com 11-22-21

[Travis Wells] earned his Juris Doctorate (J.D.) in Corporate Law from George Washington University Law School and his Master of Business Administration (MBA) in Global Sustainability and Finance from the Gabelli School of Business at Fordham University.

Malcolm X’s 5 surviving daughters: Inside lives marred by tragedy and turmoil

New York Post 11-23-21

[IIyasah Shabazz] graduated from the elite Hackley School, obtained a bachelor’s degree from SUNY New Paltz and a master’s degree in human resources from Fordham University.

Michael R. Scoma is recognized by Continental Who’s Who

PR Newswire 11-24-21

From a young age, Dr. [Michael] Scoma knew he wanted to pursue a career helping others. He started off earning his Bachelor of Science from Fordham University.

STODDARD BOWL: 2021 game will honor the former greats, Maloney’s Annino and Platt’s Shorter

MyRecordJournal.com 11-24-21

After Platt, [Michael] Shorter did a post-grad year at Choate, where he was an All-New England running back, then went on to play four years at Fordham University, where he earned a degree in Economics.

Local performer returns to state with ‘Fiddler’

HometownSource.com 11-24-21

From there [Scott Willits] went to The Ailey School and Fordham University and received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in dance in New York.

The Singer Who Calls Himself Sick Walt

Long Island City Journal 11-24-21

After graduating from Fordham University with a degree in communications and a minor in German and singing in a cover band, Sick Walt set out on a traditional (he means boring!) career path, taking what he calls a corporate “suit job” in a financial institution.

Aleksander Mici files to run for U.S. Senate

Bronx Times 11-24-21

[Aleksander] Mici, 46, is a practicing attorney with a law degree from Fordham Law School.

Robert Hughes

Citizens Journal 11-20-21

Bob [Robert Hughes] has a MA in economics from Fordham University and a BS in business from Lehigh University.

Grassroots solutions and farm fresh eggs

The Bronx Free Press 11-27-21

[Jack] Marth first connected with POTS when he was a Fordham University student in 1988, as he volunteered to help in the soup kitchen.

Suozzi enters governor’s race

The Daily Star 11-29-21

A graduate of Boston College and Fordham Law School,, [Thomas] Suozzi lives with his wife, Helen, in Nassau County.

Latino students succeed in graduate school with the support of the Hispanic Theological Initiative

FaithandLeadership.com 11-30-21

The Rev. Dr. Loida I. Martell recalls a critical, do-or-die moment she faced while pursuing a Ph.D. in theology from Fordham University.

Governor Hochul Announces 2021-2023 Fellows

Governor.ny.gov 11-30-21

[Shaquann Hunt] received a B.A. in Philosophy and Psychology from Colby College and a J.D. from Fordham University School of Law.

With Graduate Degree She Worked At McDonald’s, She Now Owns Three

Patch.com 11-30-21

Just after Sara Natalino Amato received a graduate degree at Fordham University, she went to work at an Orange McDonald’s.

Lamont nominates Nancy Navarretta as Mental Health and Addiction Services Commissioner

Fox61.com 12-1-21

[Nancy Navaretta] earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology from Boston College, and a Master of Arts degree in clinical psychology from Fordham University.

United Way Board of Directors Appoints Four New Members

Patch.com 12-1-21

[Marjorie] De La Cruz was awarded the Fordham School of Law 25th Annual Corporate Counsel Award; Latino Justice 2019 Lucero Award and was featured in Hispanic Executive in March 2019.

Jasmine Trangucci, LCSW-R is Meritoriously Named a ‘Top Patient Preferred Psychotherapist’ Representing the State of New York for 2022!

DigitalJournal.com 12-2-21

[Jasmine Trangucci] then went on to complete her Master of Social Work degree at Fordham University in 2005.

Hamilton Re-Signs Anderson as General Manager

OurSportCentral.com 12-2-21

A 2006 graduate of Fordham University, [Jermaine] Anderson earned his Master of Business Administration from the Ted Rogers School of Management at Ryerson University in September of 2019.

Hers Is a Filmmakers Festival

The East Hampton Star 12-2-21

Ms. [Jacqui] Lofaro grew up in Greenwich Village and graduated from Fordham University.

Connell Foley elects new managing partner

ROI-NJ 12-2-21

[Timothy] Corriston earned his J.D. from Fordham University School of Law and his B.A. from Hobart College. He also holds an LL.M. in environmental law from Pace University School of Law.

OBITUARY

Walter Miner Lowe, Jr.

Auburn Citizen (subscription) 11-24-21

Born in NYC, he was the son of late Walter Sr. and Florence Lowe. Walter was a 1958 graduate of Fordham University and an Army veteran serving his …

Denis Collins

Legacy.com 11-24-21

He graduated from Gonzaga High School in 1967, and attended Fordham University, with various mis-adventurous detours to Trinity College in Ireland, Talladega College in Alabama, and Stony Brook University in Long Island.

Sr. Marie Vincent Chiaravalle

Legacy.com 11-29-21

She attended St. Elizabeth Teacher College, Allegany, Fordham University in New York City and graduated from St. Bonaventure University, Allegany, with a bachelor of science degree in education.

Frank J. Messmann III

The Enterprise 11-26-21

He received a doctorate from Fordham University.

Roderick Dowling

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution 11-28-21

He received his law degree from Fordham Law School as the President of his class in 1965, paying for his tuition through multiple jobs as a waiter, lifeguard, and a Fordham scholarship.

Mary Waddell

The Atlanta-Journal 12-1-21

Mary was born in Manhattan, New York to James and Anna McHugh McGuinness on August 18, 1927. She attended St. Barnabas High School in the Bronx and graduated from Fordham University with a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemistry before joining the global headquarters of the New York City-based public relations firm Carl Byoir & Associates.

]]>

“It was not meant to be,” said Simpson, a 1970 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill.

Since then, however, he’s found his way to another role in the space race, an earthbound occupation with responsibilities that show just how complex—and potentially fraught—the exploration of the final frontier has become since his youth.

As executive director of the Colorado-based Secure World Foundation for the past seven years, he has worked with all the governments and private companies that have joined the space age since the days when the U.S. and the Soviet Union were the only two players. The foundation works for peaceful, sustainable use of outer space, taking on a whole universe of concerns as well as opportunities.

After retiring from the foundation on Oct. 1, he plans to stay engaged with the space-related initiatives it has helped advance around the world. “People are beginning to realize that there’s some real down-to-earth impact, for better and for worse, from space technology, and that’s the future,” he said.

A Career Launches

Simpson was interested in science from an early age, and edited a science newspaper as a student at Edgemont High School in Westchester County, New York. As an honors student at Fordham, he took to political science, an interest that was fueled when political science chairman James C. Finlay, S.J.—later president of Fordham—got him an internship at the New York state constitutional convention in 1967.

“How he pulled that off, I don’t know,” Simpson said. “It was mostly graduate students and seniors, and there I am, a rising sophomore, trying to figure things out.”

He later earned several advanced degrees, including a doctorate from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, and embarked on an academic career, serving as president of Utica College, the American University of Paris, and the International Space University in France before joining the Secure World Foundation in 2011.

The foundation has offices in Broomfield, Colorado, and Washington, D.C. It was established in 2002 with philanthropic funding from husband-and-wife entrepreneurs Marcel Arsenault and Cynda Collins Arsenault to bring governments, industry, and various organizations together on potentially fractious space-related issues.

One of these issues is space junk. As unbelievable as it may seem, the vastness just beyond Earth is growing crowded. “We’re at the point where we can’t any longer just sit back and say, ‘Hey, space is big, go do what you want to, you’ll be OK,’” Simpson said.

There are probably 2,000 defunct spacecraft in orbit, along with about 20,000 pieces of detectable debris—the size of a softball or bigger—because of accidents like the collision between a derelict Soviet-era satellite and a privately launched American communications satellite in 2009, Simpson said. “There may be a million pieces that are smaller than a golf ball,” he said. “Maybe pretty soon, we’re going to need a system for traffic management in space” because debris is both dangerous and hard to manage, he said.

“On Earth, we can clean up a mess because it stays in one place. In orbit, it doesn’t stay in one place. It moves, and it’s moving at 17,500 miles per hour,” he said.

Setting up a system for governments to track and mitigate the problem of debris is part of the foundation’s work with the U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. “There’s still a fair amount of trust-building that has to go on to get people to agree that this is not world government trying to take away their chance to be involved in an exciting industry,” Simpson said.

The foundation offers nonaligned expertise that can help nations work through space security issues, said Asif Siddiqi, Ph.D., a Fordham space historian who has worked with the foundation. “I think what they’re providing is a kind of nongovernmental, noncorporate perspective on space security, which is really important, and they have really good people working there who are experts in their particular fields,” he said.

The foundation’s work intersects with military issues at times, as shown by a 2017 initiative to promote greater public study of the weapons that nations are developing to disrupt or destroy satellites and other space technologies.

“Space is not the sole domain of militaries and intelligence services,” the foundation said in a statement. “Our global society and economy is increasingly dependent on space capabilities, and a future conflict in space could have massive, long-term negative repercussions that are felt here on Earth.”

Responding to Incoming Threats

Other security issues relate to incoming asteroids, and not just because of the damage they could cause, Simpson said. He noted that an asteroid burst over the Mediterranean in 2002 with the force of a nuclear bomb; if it had arrived a few hours earlier, it could have burst over the border between India and Pakistan during a military standoff between the two nuclear-armed rivals, he said. “I’m not sure that people would have been rational enough to say, ‘This wasn’t a nuclear weapon,’” Simpson said.

Since then, the foundation helped establish the International Asteroid Warning Network to help prevent such mistakes, and also has its eye on other potentially dangerous scenarios—such as, for instance, one nation intimidating and alarming other nations to the point of crisis by firing a nuclear weapon at an incoming rock.

The foundation works through the U.N. to try to set guidelines for nations’ responses and has brought experts together to talk about how to alert the public to a threat without sparking panic, Simpson said. The foundation’s Broomfield Hazard Scale provides a uniform guide for the threat posed by an asteroid.

“Governance, in effect, is the key thread that I think ties together a lot of our work,” Simpson said. For instance, he said, “if there were no plan for dealing with car accidents, there would probably be a lot more fights around [them]. Most folks, at least, don’t reach in the glove box for a firearm, we reach in for a document. We have a process, know what we’re supposed to do, don’t have to invent it after a challenge occurs. That’s what we’re trying to do with space.”

The foundation works on a wide portfolio of issues, including—recently—an effort to come up with basic rules covering the mining of asteroids and near-Earth objects, Simpson said. In early 2018, he went to the Vatican Observatory for meetings about how to link the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals to Space 2030, the emerging global agenda for space activity.

Boundless Opportunities

Space activity remains Simpson’s passion not so much for the science but for its impact on people, an outlook rooted in his political science studies at Fordham—“politics has rules, but people are at the core,” as he put it.

He noted that space has fostered medical advances; the weightlessness of space has shed light on the role of weight-bearing exercise in staving off osteoporosis, he said. Developing nations have used GPS satellites to synchronize their cell towers, expanding cell service without having to set up their own synchronization systems. And crop disease can be detected from satellites, thanks to spectrographic technology that can spot color changes associated with blight.

In other words, all the security worries surrounding space technology are mixed with new possibilities for improving life on Earth.

“It’s mind-boggling. You’d think that the time would come when you cease being amazed by what people are doing,” he said. “[I] really enjoy not only having entered the space sector but the opportunity to continue to work with it, because it just keeps solving problems for people.”

After stepping down as executive director of the foundation, he’ll keep working with various groups devoted to space-related issues. His first stop will be the 69th International Astronautical Congress in Bremen, Germany, where he’ll present a paper on the role of NGOs in the development of international space policy. “Life shows no signs of slowing down,” he said.

]]>

“There’s been a bunch of declassifications on Sputnik. These have been going on for maybe the last 10 years or so, [and]in terms of the origins of Sputnik, a lot has come to light since the 50th anniversary.

“One of the things that I want to focus on is the idea of the space race itself, which we mark as beginning on October 4, 1957.

“Looking at these documents, the first thing that I think strikes us is that the space race really began even before Sputnik, in perhaps around 1955 or so.

Speculative News

“A key player in all this is Sergei Korolev, who is sort of the architect of the Soviet space program, a very leading designer in the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s [and]a space enthusiast as a young man. But in the early 50s, he was in charge of the ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile) program, and really wanted to put something in orbit, [he]was fascinated by space, and there were like-minded people around him. But there was no really firm way to do so. But he had something that now we’re beginning to realize— a lobby of people around him, also space enthusiasts who were engineers.

“In 1954 . . . because they knew a lot of Soviet journalists, they flooded the Soviet media with speculative articles on space flight.

“A bunch of articles just started coming out in early ‘54, and into ’55. The interesting thing is, a lot of really powerful people began to take notice, especially of one article that came out, I believe, in April of 1955. This article [got]cited a lot in the Washington Post and New York Times, this Soviet, Russian-language article. It eventually makes its way into the CIA, and if you look at some the rationales behind the first U.S. satellite, it’s a complicated story involving freedom of space. But one of the things inserted into the very high-level documents like the 1950s National Security Council documents, is this article, which Korolev and his colleagues had orchestrated.

“There was nothing going on in the Soviet Union on space at this time, but this article [got]repeated and circulated a lot, and, as probably all of you know, in the end of July 1955, the Eisenhower administration announces they’re going to launch a satellite in a couple of years, it’s going to be a scientific satellite.

“There are all sorts of reasons that happens, but one of those I think is this Russian media thing.

A Circular Argument

“As soon as the announcement happens, Korolev writes a letter to the Politburo on August 5, and he says ‘look, these guys are going to launch a satellite,’ and he attaches stuff from the New York Times and the Washington Post talking about the Russians launching a satellite. So it’s a circular argument.

“Three days later, on August 8, the Politburo meets, and they sign off on this, and Korolev gets his approval.

“There’s a kind of back and forth about what the Americans are doing, and the [Soviets] start a program to launch a much smaller satellite, which is the Sputnik that we know—the size of a basketball with antennas and a battery and a radio transmitter.

“So the space race, I think, had already begun in the minds of the Russian engineers in 1954, 1955, and they’re already moving the pieces in anticipation of what the Americans are doing, and the Americans are already moving the pieces in anticipation of what the Soviets might do.

“Besides just being captivated by space, these guys needed something else. And that was competition: something to compete with and compete against, to advocate your position to the top-level leadership.

“Finally, they were opportunists in the sense that they were scientists and engineers using a moment to wedge into the policy process and get something done. The existence of a lobby, the ability to be opportunistic at a given moment, and the ability to leverage some sort of competitive aspect, I think, were in the mix already in the 1950s on the Soviet side. That’s why these declassifications of all these documents are so interesting, because they provide a view into things that we now see in contemporary space all the time.”

]]>

(Photo by Bill Denison)

This year’s diverse group of fellows was chosen from among 3,100 applicants within the United States and Canada, the foundation announced on April 9. Fellows are selected for their “impressive achievement in the past and exceptional promise for future accomplishment” and are given a wide berth in which to engage in research in any field of knowledge or in any of the arts.

A scholar of the history of space exploration, Siddiqi is the author of The Rockets’ Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957 (Cambridge, 2010) and Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974. He is a member of the National Research Council’s Committee on Human Spaceflight, tasked by Congress to review the long-term goals of the U.S. human spaceflight program.

He said he plans to use the fellowship to produce a global history of the human footprint left behind from the development of spaceflight, mapping places across continents where communities and cultures were transformed by such activities.

“There are literally dozens of places …, most of them abandoned now, that have the detritus of human activity from rockets and satellites,” said Siddiqi, whose interest includes how scientific elites interacted with the local populations.

Ultimately he hopes to produce an account, and possibly a museum exhibit, that is part history, part ethnography, and part oral history of what he calls the “departure gates” of spaceflight from Earth.

Guggenheim fellowships are awarded for a minimum of six months and a maximum of 12 months, with the size of the grant varies. The fellowships were established in 1925 by former U.S. Senator Simon Guggenheim and his wife, in memory of their 17-year-old son, John Simon Guggenheim, who died in 1922 of a bacterial infection before he was to leave for college.

— Janet Sassi

]]>

Photo by Bill Denison

1. Humans have built five objects

that have left or are about to leave the solar system.

Once they leave, they will wander in various directions away from our sun into the interstellar medium. Even if our planet were to be destroyed today, these five spacecraft would still be traveling out towards the cosmos as remnants of humanity. The farthest of the five, indeed the farthest human-made object, is Voyager 1, which is about 12 billion miles away from the Earth and still transmitting data back.

2. The most exciting activity in space exploration in recent years has been in robotic exploration.

In 2005, a European space probe successfully landed on Saturn’s moon Titan. Currently, a NASA probe known as New Horizons is speeding its way to the dwarf planet Pluto (which it should reach in the summer of 2015). In 2006, a spacecraft called Stardust parachuted down in a remote range in Utah, having flown into a comet at a speed of 3.7 miles per second, captured its dust, and brought it back to Earth. Another NASA spacecraft, NEAR, successfully landed on the asteroid Eros in 2001.

3. Most of the money the world spends on civilian space activities is not for exploration or fundamental science but rather for what practitioners call “applications” goals.

Space activities now provide daily services to both scientists and citizens that we take for granted. These include satellites that:

• assess and analyze the natural resources of the Earth using remote sensing;

• help industries such as agriculture and fisheries to thrive;

• study climate change;

• help save people and resources from natural disasters such as cyclones, earthquakes, floods, and droughts;

• enable international agencies to provide humanitarian assistance during crises;

• help us locate ourselves through the Global Positioning System (GPS);

• tell us detailed weather predictions;

• and support telecommunications over mobile phones, TV broadcasting, and the Internet.

4. The annual NASA budget is much much (much) smaller than the following things:

The amount we spend annually on pizza. Or tobacco. Or illegal drugs. Or gambling. The annual budget of NASA is about 0.5 percent of our gross national product, or about $17.6 billion. By comparison, federal spending on other programs includes $1 trillion (defense, veteran’s services, and homeland security), $78.3 billion (health and human services), and $71.2 billion (education).

5. For the past 13 years and counting, there has always been someone in space.

Since October 31, 2000, when three astronauts lifted off to live aboard the International Space Station that orbits the Earth, crews have constantly rotated aboard that facility, maintaining a continuous human presence in space. So whenever you look up into the sky, no matter the time of day or night, you can be confident that there are astronauts living and working in space. But are long stretches in space healthy? Medical experts concede that very long-term stays, such as the 437 days-in-space record held by Russian astronaut Valery Polyakov, can have serious negative consequences to human health, including loss of bone mass, decrease in eyesight, loss of appetite, and problems in blood flow. Missions beyond Earth orbit can make these problems much worse due to the dangers of cosmic radiation.

6. The United States has a parallel secret space program that is not run by NASA but rather by the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO).

The NRO has the largest budget of any U.S. intelligence agency, comparable in size to that of NASA. (Its actual budget is classified). Most of the NRO’s activities are conducted in secret, and the agency does not describe its activities (which includes spying) in any detail. Many of their (very) expensive satellites are launched from a site in Southern California (instead of Cape Canaveral in Florida). Imagery collected by the NRO is analyzed by another little-known organization, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

7. The foundation of the modern rocket is the German V-2 built by German scientists and engineers during World War II.

Many of the Germans who worked on the V-2 later came to the United States and worked on the development of the Saturn rocket that lifted American astronauts to the Moon. Many of these men had been active Nazis, but their unsavory pasts were whitewashed out of history in service of the Cold War. For example, Arthur Rudolph, who was NASA’s project director for Saturn was involved in atrocities at the infamous Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp in Germany. In the early 1980s, when the truth about his activities came out, Rudolph renounced his American citizenship and fled the United States rather than face war crimes trials.

Photo courtesy NASA/James B. Irwin

8. Polls suggest that about 6 percent of the American population still believes that the Moon landings were faked.

In other countries, this number is much higher, as high as 28 percent in a recent Russian poll. Belief in the “faked Moon landings” taps into a deep-rooted belief in conspiracies in American culture, such as those about the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the death of Elvis, UFOS, 9/11, and such. The persistence of such beliefs also perhaps highlights a powerful current of hostility toward science in American culture (such as that manifest in creationism).

-By Asif Siddiqi

]]>The Bronx River Rats, of course.

Fordham’s unofficial faculty band will be back at it for their Fifth Anniversary of Dr. N’s Rhythm Review on Saturday, April 2 at 7:30 p.m. in the McGinley Center Ballroom. The event is a fundraiser for the University’s Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP).

Who can resist coming out for an event that promises rock, rhythm & blues, and old soul favorites by actual Tenured Professors? This year there is even a dance contest.

You won’t want to miss this:

Or this:

So far, those faculty performing include Mark “Notorious Ph.D.” Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African-American studies, Paul “Dr. Blues” Cimbala, Ph.D., professor of history, Christophe “Daddy” Chalamet, Ph.D., associate professor of theology and Asif “Punk” Siddiqi, Ph.D., associate professor of history, but there are likely to be some other add-ons (perhaps even a dean, who knows?)

Fordham’s student acappella group, the Satin Dolls, will open the set. For an idea of what you are in for, read a review here. Tickets are $10, $5 with student i.d., and all proceeds go to the BAAHP.

–Janet Sassi

]]>In The Red Rockets’ Glare: Spaceflight and The Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957 (Cambridge, 2010), the assistant

(Photo by Bill Denison)

professor of history deconstructs the Soviet Union’s obsession with the fantasy of space exploration and the technology that catapulted the Communist country into the space race of the 20th century.

“Why is it that the Russians sent Sputnik into space in 1957, when the government wasn’t terribly interested?” Siddiqi asked.

The answer, he said, starts in the early 20th century with Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, an eccentric Russian schoolteacher who lived reclusively in a small village. A fan of Jules Verne and other science fiction writers, Tsiolkovsky was also a mathematician. In 1903, he developed an equation in theoretical astronautics for a viable rocket.

“Tsiolkovsky had a particular passion for space travel—how to get there, what to do when we arrived, and why we should go,” said Siddiqi, a specialist in Russian history. “He was a bit of an eccentric who believed that people went into space once they died, but he was an inspirational character for a generation of space enthusiasts in the 1920s.”

In the 1920s, there was a huge global interest in space and the cosmos, indicated by the rise in mass-market science fiction literature and popular cinema. In early Communist Russia, amateur clubs and organizations—inspired by Tsiolkovsky’s writings and dreams of space travel—began building homemade rockets.

“In Russia, there was an emergence in the late-19th century of a mystical notion of the cosmos that was often occultish,” Siddiqi said. “But by the 20th century, an explosion of sci-fi helped redirect that mystical interest into scientific and technical directions.”

Through archival research, Siddiqi found that many of those amateur clubs approached the government for funding to build. Turned down initially, they returned with a different strategy: If the government would fund their rocket construction, the rockets could be used to launch military weapons.

As rocket enthusiasts grew more sophisticated, so did the types of weapons being invented. With the escalation of the Cold War, the Soviet government became more interested in how to launch missiles against targets across the globe.

“By the 1950s, these young rocket enthusiasts were managers of the Soviet missile mission, hired to develop a way to deliver an atomic bomb on the United States,” Siddiqi said.

One such scientist was Sergei Korolyov. In the 1930s, Korolyov had been part of a state-sponsored center for rocket development. But when Stalin came to power, Korolyov was fingered as a dissenter and sent to a gulag in Siberia, and then to an internment camp for scientists.

Korolyov worked his way back into favor inside the Cold War bureaucracy in the late 1940s and, by the 1950s, became head of the nation’s intercontinental missile program under Nikita Khrushchev.

It was the height of the Cold War and the Soviet government was not at all preoccupied with going into space.

“But Korolyov had not abandoned that dream,” Siddiqi said.

Aware of the deep rivalry between the Soviets and the United States, Korolyov began collecting articles from American newspapers on U.S. plans to launch a satellite into space. “The only way to convince the Soviet government to launch a space satellite was to say, ‘The Americans are thinking of doing this. We need to do it, too,’” Siddiqi said.

Siddiqi obtained declassified correspondence in which the Korolyov used the clippings to persuade Khrushchev to give him “a couple of rockets” for space instead of for weapons. Within two years, Sputnik was ready: On Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviets sent the first satellite into space, beating America to the punch.

Even then, Siddiqi said, Khrushchev was nonplussed. Interviews with Khrushchev immediately after successful orbit, said Siddiqi, showed the Soviet leader’s reaction to Sputnik to be “lukewarm” at best.

But when the Western press splashed the news on front pages with the bold, banner headline, “SPUTNIK LAUNCHED,” the Soviets suddenly paid attention. “The Soviets reacted to the reaction,” Siddiqi said. “Once the Russians saw that Korolyov’s side project had caused a global furor, they appropriated and exploited it.”

Today, Tsiolkovsky and Korolyov are national heroes in Russia, with their likenesses found on public monuments across the nation. In fact, the town of Kaliningrad was changed to Korolyov in 1996, and the 1987 ruble bore an image of Tsiolkovsky, who has a namesake crater on the moon.

“Under a very strong, repressive government, you’d expect that popular enthusiasm wouldn’t play a role,” Siddiqi said. “But with regard to the space race, I found that popular support played a huge part.”

In fact, he said, the Russian venture into space couldn’t have happened without it.

“You need both the science and the utopianism, the amateur groupsand the government,” he concluded, “and perhaps even a little irrational justification.”

Working on The Red Rockets’ Glare has inspired some side projects. These include an analysis of the bourgeoning Indian space program and a further historical account of Soviet scientists who did their research in internment camps under Stalin.

“To write the histories of those repressed societies, it is not enough to write just about the leaders,” Siddiqi said. “It is as—if not more—important to take the challenge of recording the lived experiences of the ordinary people.”

– Janet Sassi

]]> On the night of October 4, 1957, a Soviet rocket lifted off from a location deep in Central Asia, and tracing a majestic arc over the barren desert, began accelerating toward the heavens. Within five minutes, as its engines fired an inferno of flames into the thinning atmosphere, the rocket was flying faster than anything ever flown. Seconds later, the small metal ball at the tip of this conflagration entered a free fall orbit around the Earth.

On the night of October 4, 1957, a Soviet rocket lifted off from a location deep in Central Asia, and tracing a majestic arc over the barren desert, began accelerating toward the heavens. Within five minutes, as its engines fired an inferno of flames into the thinning atmosphere, the rocket was flying faster than anything ever flown. Seconds later, the small metal ball at the tip of this conflagration entered a free fall orbit around the Earth.

For the first time since life appeared on our planet, an object made by humans had escaped the bonds of gravity. Known as Sputnik—Russian for “fellow traveler”—this first artificial satellite fell from orbit within a few weeks. Despite its early demise, Sputnik has remained in our collective imagination not only as a potent symbol of the political, social, and cultural possibilities of the late 20th century, but also as a metaphor for human aspirations for an exhilarating future.

Inherent in Sputnik’s languid passage over American skies were three embedded narratives. One communicated wonder. Sputnik opened up a (metaphorical and literal) universe. The physical limits of our dreaming burst open, revealing the endless possibilities of the cosmos, not as a source for the fictions of our childhood but as a font for the hopes of many futures. Another message was about threat. Any nation that could lob a piece of metal into orbit could certainly replace that metal with an atomic bomb. Fear was a palpable response in the American context. The third narrative was one of priority. Economic and military success had made Americans self-satisfied and uninterested in the outside world. How could a foreign nation, best associated with Godless culture and backward agriculture, beat the Americans? Sputnik put the Soviet Union on the map—as enemy, as adversary, as equal.

In the United States, Sputnik shocked a seemingly complacent society, secure in its middle class mores, new suburbs, color televisions and the highest peacetime budget in history. The satellite, launched on the same night that Leave it to Beaver premiered, awoke a nation. Historian Walter McDougall noted that “[n]o [single]event since Pearl Harbor set off such repercussions in public life.” A crisis of confidence washed over most of American society.

In government, the Eisenhower Administration produced legislation to create several new agencies, including NASA. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy set the goal of landing an American on the Moon before the end of the decade. Galvanized by a brief period of Congressional consensus and support, NASA marshaled $25 billion and the efforts of hundreds and thousands of Americans. Within eight years of Kennedy’s commitment, Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon.

NASA was not the only beneficiary of Sputnik. Government-funded projects to improve the scientific and engineering expertise vastly expanded. Believing that better education in Russia contributed to Sputnik, huge amounts of money poured into the American higher education system, making it a key component in the battles of the Cold War. Long-standing policy that education was better left to the states was abandoned. Noting that “an educational emergency exists and requires action by the federal government,” Congress passed the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) in 1958. The act more than doubled federal expenditures for education; money was allotted for student loans, graduate fellowships in the sciences and engineering, aid for teacher education, capital construction, as well as curriculum development in the sciences, mathematics and foreign languages. Simultaneously, billions of dollars poured into government agencies, private industry and universities to fund basic and applied research. In an undeniable way, Sputnik made American higher education and R&D a key component in the Cold War. The unprecedented response to Sputnik fundamentally tied the university, the defense establishment and private industry in a partnership that remains unbroken to this day.

In the lead up to the recent 50th anniversary of Sputnik, many commentators expressed a nostalgia for America’s post-Sputnik response. They argued that the collective mobilization after Sputnik represented the best America had to offer. In many ways, such exercises in wistfulness are misplaced for they simplify the complexities of the 1960s, occluding from view immense social and cultural conflicts of that decade. These nostalgic laments for Sputnik are less about history than about the perceived ennui in American society today.

Some have argued that it would take a major shock to the nation to galvanize it again, perhaps China sending an astronaut to the Moon or to Mars. I doubt whether such an achievement would have the same effect as Sputnik. Space no longer holds the imagination as it once did, and few young Americans are drawn to the possibilities of the cosmos. And perhaps rightly so. We as human beings have created an almost unimaginable array of problems on our earthly abode.

Yet, it is because of the messiness of our postmodern condition that I am also nostalgic for Sputnik. Nostalgic not for what transpired in the years after Sputnik, not for the 1960s, and not for the iconography of the Apollo Moon missions. My nostalgia is one for the future that Sputnik represented at a singular moment in time. The wonderfully elegant design of the satellite—the brainchild of engineer and Gulag survivor Sergei Pavlovich Korolev—suggests a motif that is about hope. The metal ball with its four antenna, angled as if in concordance with some graceful arc through the heavens, suggests movement, a hope for an essentially transcendental transformation that is possible only at singular moments. October 4, 1957, was such a moment when the whole future of the human race was broken wide open for us to dream. In remembering Sputnik, it is this narrative, the one about wonder, not about fear or insularity, that I find most enduring. The good thing about the future is that it is always unlived. We can still hope for the best.

The “Sapientia et Doctrina” section of Inside Fordham features first-person columns written by members of the Fordham Jesuit community and University faculty. Our Jesuit correspondents offer essays on teaching and learning from a Jesuit perspective, or focus on some aspect of scholarship as seen through the lens of Jesuit tradition. Faculty correspondents write on an academic topic: their own academic specialty or current research; or an aspect of scholarship, written for the lay person. The two types of columns alternate by issue.

For more information, please contact the editor, Victor Inzunza, at (212) 636-7576, [email protected].

]]> Asif Siddiqi, Ph.D.

Asif Siddiqi, Ph.D.Assistant Professor of History On the night of October 4, 1957, a Soviet rocket lifted off from a location deep in Central Asia, and tracing a majestic arc over the barren desert, began accelerating toward the heavens. Within five minutes, as its engines fired an inferno of flames into the thinning atmosphere, the rocket was flying faster than anything ever flown. Seconds later, the small metal ball at the tip of this conflagration entered a freefall orbit around the Earth.

For the first time since life appeared on our planet, an object made by humans had escaped the bonds of gravity. Known as Sputnik—Russian for “fellow traveler”—this first artificial satellite fell from orbit within a few weeks. Despite its early demise, Sputnik has remained in our collective imagination not only as a potent symbol of the political, social, and cultural possibilities of the late 20th century, but also as a metaphor for human aspirations for an exhilarating future.

Inherent in Sputnik’s languid passage over American skies were three embedded narratives. One communicated wonder. Sputnik opened up a (metaphorical and literal) universe. The physical limits of our dreaming burst open, revealing the endless possibilities of the cosmos, not as a source for the fictions of our childhood but as a font for the hopes of many futures. Another message was about threat. Any nation that could lob a piece of metal into orbit could certainly replace that metal with an atomic bomb. Fear was a palpable response in the American context. The third narrative was one of priority. Economic and military success had made Americans self-satisfied and uninterested in the outside world. How could a foreign nation, best associated with Godless culture and backward agriculture, beat the Americans? Sputnik put the Soviet Union on the map—as enemy, as adversary, as equal.

In the United States, Sputnik shocked a seemingly complacent society, secure in its middle class mores, new suburbs, color televisions and the highest peacetime budget in history. The satellite, launched on the same night that Leave it to Beaver premiered, awoke a nation. Historian Walter McDougall noted that “[n]o [single]event since Pearl Harbor set off such repercussions in public life.” A crisis of confidence washed over most of American society.

In government, the Eisenhower Administration produced legislation to create several new agencies, including NASA. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy set the goal of landing an American on the Moon before the end of the decade. Galvanized by a brief period of Congressional consensus and support, NASA marshaled $25 billion and the efforts of hundreds and thousands of Americans. Within eight years of Kennedy’s commitment, Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon.

NASA was not the only beneficiary of Sputnik. Government-funded projects to improve the scientific and engineering expertise vastly expanded. Believing that better education in Russia contributed to Sputnik, huge amounts of money poured into the American higher education system, making it a key component in the battles of the Cold War. Long-standing policy that education was better left to the states was abandoned. Noting that “an educational emergency exists and requires action by the federal government,” Congress passed the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) in 1958. The act more than doubled federal expenditures for education; money was allotted for student loans, graduate fellowships in the sciences and engineering, aid for teacher education, capital construction, as well as curriculum development in the sciences, mathematics and foreign languages. Simultaneously, billions of dollars poured into government agencies, private industry and universities to fund basic and applied research. In an undeniable way, Sputnik made American higher education and R&D a key component in the Cold War. The unprecedented response to Sputnik fundamentally tied the university, the defense establishment and private industry in a partnership that remains unbroken to this day.

In the lead up to the recent 50th anniversary of Sputnik, many commentators expressed a nostalgia for America’s post-Sputnik response. They argued that the collective mobilization after Sputnik represented the best America had to offer. In many ways, such exercises in wistfulness are misplaced for they simplify the complexities of the 1960s, occluding from view immense social and cultural conflicts of that decade. These nostalgic laments for Sputnik are less about history than about the perceived ennui in American society today.

Some have argued that it would take a major shock to the nation to galvanize it again, perhaps China sending an astronaut to the Moon or to Mars. I doubt whether such an achievement would have the same effect as Sputnik. Space no longer holds the imagination as it once did, and few young Americans are drawn to the possibilities of the cosmos. And perhaps rightly so. We as human beings have created an almost unimaginable array of problems on our earthly abode.

Yet, it is because of the messiness of our postmodern condition that I am also nostalgic for Sputnik. Nostalgic not for what transpired in the years after Sputnik, not for the 1960s, and not for the iconography of the Apollo Moon missions. My nostalgia is one for the future that Sputnik represented at a singular moment in time. The wonderfully elegant design of the satellite—the brainchild of engineer and Gulag survivor Sergei Pavlovich Korolev—suggests a motif that is about hope. The metal ball with its four antenna, angled as if in concordance with some graceful arc through the heavens, suggests movement, a hope for an essentially transcendental transformation that is possible only at singular moments. October 4, 1957, was such a moment when the whole future of the human race was broken wide open for us to dream. In remembering Sputnik, it is this narrative, the one about wonder, not about fear or insularity, that I find most enduring. The good thing about the future is that it is always unlived. We can still hope for the best.

The “Sapientia et Doctrina” section of Inside Fordham features first-person columns written by members of the Fordham Jesuit community and University faculty. Our Jesuit correspondents offer essays on teaching and learning from a Jesuit perspective, or focus on some aspect of scholarship as seen through the lens of Jesuit tradition. Faculty correspondents write on an academic topic: their own academic specialty or current research; or an aspect of scholarship, written for the lay person. The two types of columns alternate by issue.

]]>

Photo by Ken Levinson

It was a Fordham first: Brennan O’Donnell, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill, Paul Cimbala, Ph.D., professor of history, and Asif Siddiqi, Ph.D., assistant professor of history, jammed onstage with friends in the McGinley Center Ballroom on March 3 before a crowd of 200 at a fundraiser for the University’s Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP).

Dubbing themselves “Dr N’s Rhythm Review,” a name inspired by Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African-American studies, and principal investigator of the BAAHP, the faculty band cruised through two sets of rock, rhythm & blues and soul favorites, inspiring the audience of students, faculty and friends to get funky on the dance floor.

Naison, who emceed the evening, opened the performance with a hip-hop “educational rap,” and followed it with a dance featuring some fancy footwork in a pair of time-worn, stiletto-toed shoes. Onstage, band leader Cimbala announced a B.B. King favorite, and playfully encouraged his students to dance if they wanted to “pass their Ph.D.s.” He also invited younger faculty members onto the floor.

“You guys are still in shape — you’re not old like we are,” he said.

Wearing a “Blues for Peace” baseball cap and adroitly picking his Gibson guitar, Cimbala offered some bluesy vocals, his tremolo evoking “yeas” and “all rights” from the pleased crowd. He was backed on rhythm guitar by Siddiqi, whose raw thrumming and garage-band experience earned him the title “master of the Stratocaster” from his co-workers.

“He doesn’t have tenure yet,” Cimbala, teased. “But he’s willing to stick his neck out anyways and play with us.”

Photo by Ken Levinson

Dean O’Donnell, sporting jeans and a maroon Fordham baseball cap, played bass, plucking the strings with impressive dexterity and rocking to the music. The other band members were Annmarie Davis on vocals, Ronnie Negro on drums, sociology doctoral candidate Andrew Tiedt on percussion, John Sopko on keyboards and Anthony Marcatillo on sound system. Lizzie Grant, a Fordham College at Rose Hill junior, also sang.

In a special highlight performance, Mark Chapman, Ph.D., associate professor of African and African-American studies, joined the band for a special rendition of Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Ready.” Despite a few feedback problems, Chapman’s resonant baritone earned large applause.

Following a brief intermission, Naison performed a “serious flow” rap called “Get Your Bush On,” which he dedicated to P.S. 140 staff members in the audience. The Bronx-based elementary school is a major participant in BAAHP’s Oral History Project. Nicknaming himself the “Notorious Ph.D.,” Naison rapped to the rhythm of Herbie Hancock’s “Chameleon” on the importance of unity among the races.

The benefit raised funds for BAAHP, a project dedicated to uncovering and documenting cultural, political, economic and religious histories of African-Americans in the Bronx.

The collaboration inspired a solemn promise from Cimbala, who spearheaded the event, to do it again next year.

“Not bad for a bunch of professors,” Naison said.

– Janet Sassi

]]>