Like many universities, Fordham suspended its sports programs in 1943. “The war, lack of students, and the advent of the Army [have]curtailed all extra-curricular activities,” the 1944 Maroon yearbook staff wrote.

In June 1943, the gym and much of campus were given over to the U.S. War Department, which selected Fordham to host two units of the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP). For nearly a year, Fordham Jesuits and lay professors taught upward of 800 troops pre-engineering and languages. The goal of the program was to meet the wartime need for technically trained junior officers and soldiers. The troops in training slept in the gym, and at the program’s height, cafeteria workers were dishing out more than 2,750 meals from 4 a.m. to midnight every day.

Many of the undergraduate students who remained on campus—including basketball star Bob Mullens—were members of Fordham’s ROTC program and would soon leave Rose Hill for active duty. The ASTP troops were a much-needed infusion of life and revenue for Fordham, which had seen a precipitous decline in enrollment, from 8,100 in October 1940 to 3,086 four years later.

With “most of the athletes gone” to enlist in the military by their senior year, the 1944 Maroon editors decided to revisit earlier victories, including the basketball team’s “drive for national fame” in 1943, when Mullens led the Rams to their first National Invitation Tournament berth and became the third Fordham basketball player to earn All-America honors. That “last court team to don the Maroon colors until peace [is] restored … proved to be on par with the ‘greats’ of the past,” they wrote.

RELATED STORY: Celebrating 100 Years of Rose Hill Gym: A Thrilling Legacy

]]>“Making the transition from the military is not an easy feat. We know this,” said Matthew Butler, a former master sergeant in the U.S. Marine Corps who now serves as senior director of Fordham’s Office of Military and Veterans’ Services, in his address to students and alumni at one of the events. “And we want to give you all the support and preparation needed to make sure you land the job that you want.”

Networking with the FBI, Morgan Stanley, and NBC Universal

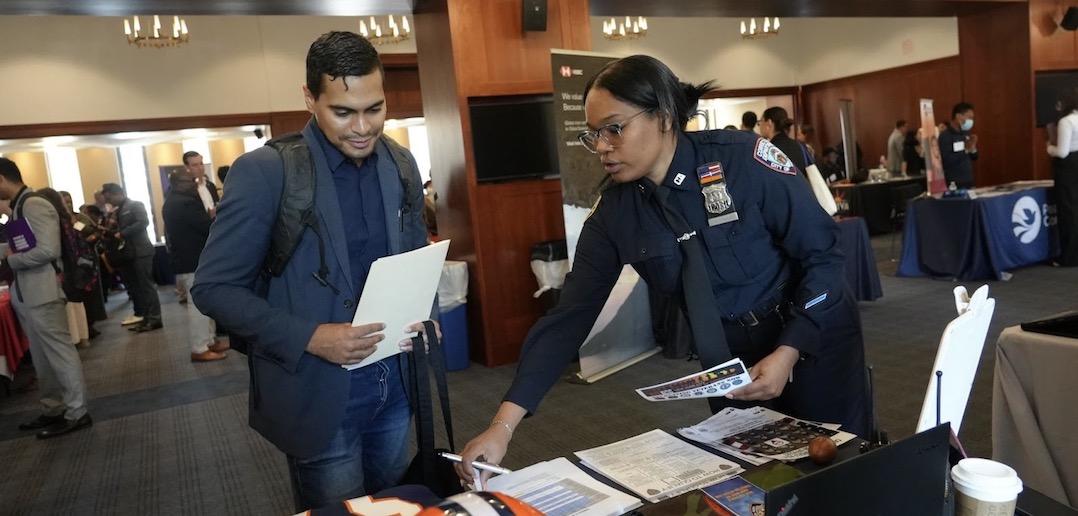

About 140 student veterans and alumni from 11 schools attended Veterans Career Day and Student Veteran Internship and Career Fair at the Lincoln Center campus. At Veterans Career Day on Oct. 4, students and alumni took free LinkedIn headshots, polished their resumes, and practiced their elevator pitch with industry professionals, some of whom were student veterans themselves. The next day, they attended the internship and career fair, held specifically for student veterans, where they had the opportunity to network with representatives from more than 30 organizations, including L’Oreal, the Federal Reserve Board, Morgan Stanley, the FBI, and NBC Universal.

Both undergraduate and graduate students from varied disciplines, including art history, economics, and finance, came to the career fair.

Among them was Steven Gutierrez, 32, an MBA student at the Gabelli School of Business. Gutierrez was born and raised in the Bronx and went on to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps for about a decade. He was dispatched all over the world—to Afghanistan, Central America, France, Italy, Japan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Switzerland, and other locations—where he served as a radio technician and officer. He now works in Fordham’s Career Center as the veterans career liaison, where he helps his peers navigate the next chapter of their lives—charting their career path.

“Typically, student veterans have worldwide experience. They bring with them discipline and accountability. The experience that they had in any of the services, it’s translatable and needed,” said Gutierrez, who plans on becoming a consultant.

From Serving as an Airborne Combat Medic to Studying at Fordham

Glenmore Marshall, a student at Fordham’s School of Professional and Continuing Studies, attended both Veterans Career Day and the Student Veteran Internship and Career Fair.

“I came to this event to find a way to better myself,” said Marshall, 37, who was born in Jamaica and grew up in the U.S. “I want to put my best foot forward and see what’s out there.”

After attending several workshops at Veterans Career Day, he said he realized that he was “underselling” his two years of experience as a U.S. Army airborne combat medic.

“I have a lot of skills I’m not showing to employers: specific skills like leadership, attention to detail, and being able to work under extremely stressful situations. As a combat medic, for example … I have to do blood transfusions. … I had to do one on a lieutenant in a Humvee in the middle of nowhere before,” said Marshall, who served in several states across the U.S., including North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Texas. “This [career readiness]workshop helped me realize … that I should utilize my background as a veteran to my advantage and not undersell myself.”

At the fair, Marshall—an information and technology major who is looking for a job or an internship—spoke with representatives from several organizations, including the Peace Corps and IPG Health. “More people should come out to this type of thing because even if you don’t necessarily get hired or get the job, the experiences you get from today, you can apply elsewhere and realize the soft skills that you didn’t know you had,” said Marshall, who aims to become a technician or consultant.

Providing Opportunities for the Larger Community

Miguel-Angel Sandoval, 30, a senior real estate major at PCS and vice president of Student Veterans of America at Fordham, said the Student Veteran Internship and Career Fair was his first-ever career fair.

“A lot of the representatives of these corporations were welcoming and willing to have a conversation with you, understand who you are … and how they can get you to fit in there,” Sandoval said. “They want to see you excel. They want to see you employed, so they’re willing to do the extra work in getting to know you as well as you getting to know them.”

Sandoval added that he is “forever grateful for Fordham.”

“Fordham does everything it can to provide every opportunity to all its students, no matter who they are—student veterans or regular traditional students,” said Sandoval, who served in the U.S. Army for more than five years in South Korea and West Point, and is still serving as an Army ROTC cadet. “Over 30 employers came out specifically to speak to us, and I think it’s a blessing.”

The events were co-sponsored by Fordham’s Office of Military and Veterans’ Services, Fordham’s Career Center, Student Veterans of America at Fordham, and multiple outside partners and institutions, including Columbia University, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Pace University, Lord, Abbett & Co. LLC, RSM US LLP, Baker Tilly, and Jetro Restaurant Depot.

“We open our doors to our fellow veterans because we know having hope and purpose in the future is an antidote to the inevitable dark days ahead or when the road gets rough,” said Butler. “A job can be the thing [where]one finds both purpose and a better future, while continuing to serve others and paying it forward.”

]]>“Things are happening at a scale which I could not imagine,” said Andriy Zelinskyy, S.J., during a short visit from the front lines of the war in Ukraine.

Father Zelinskyy made a 28-hour last-minute trip from Kyiv to the Bronx at the invitation of Fordham’s Army ROTC/Military Science Program and the Center on Religion and Culture after the campus Jesuit community helped make the connection. He was told by his commander last Tuesday that he had been granted a four-day leave.

After spending part of the day with cadets from eight colleges and universities who participate in the ROTC program at Fordham, the chaplain spoke to a crowd of more than 200 in the Keating Hall auditorium on March 2. LTC Paul Tanghe, director of the ROTC program and professor of military science, led a one-on-one discussion with the chaplain followed by questions from the audience.

“The greatest surprise for me is that a human being in the 21st century can be so cruel,” he said. “There is no reason for all this violence.” While he believes there is good in everyone, Zelinskyy said acts committed by Russian troops are empirical evidence of the damage caused by a corrupt society where people are so “unfree.”

The atrocities he has witnessed he only alluded to, but he said it is clear to him that Russian soldiers have been so indoctrinated they don’t know how to be human. He cited as an example the bombing of a theater clearly marked as having children inside. “That pilot knew what he was doing. There was no danger. There was no one standing over his shoulder (making him drop the bomb).”

Father Zelinskyy said that while we think of the war as a year old, he has served as a combat chaplain for nine years—since Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014, serving unarmed alongside soldiers on the front lines. A chaplain for 17 years in all, he served most of that time as a volunteer while advocating for Parliament to structure a formal role for chaplains in the armed forces. It did so in 2021.

He calls the role of combat chaplain “humble, but a very rich and effective ministry.” He said, “Chaplains have to find a way to share feelings with the soldiers and find sense even in the suffering. Friendship is one of the best ways. For me personally, the greatest reward is when you feel that you can unite people and reinforce them.”

An audience member asked what the rest of us can do to help.

“Don’t give up on the truth. Don’t give up on justice, on what’s really good. Don’t stop contemplating the beauty of the human heart. Stay human. That’s our responsibility,” Father Zelinskyy concluded.

The “Chaplain in Combat” audience included a contingent of 20 U.S. Army chaplains as well as a New York Army National Guard chaplain. Members of the Jesuit community, Fordham Ukrainian Society students, and Fordham College at Rose Hill Dean Maura Mast also attended.

“Fordham is the flagship of the military-connected community in New York City,” said Tanghe. This event was part of a yearlong celebration of the University’s 175-year military legacy.

]]>Tradition holds that Fordham’s military heritage dates from 1848, when the state of New York issued Fordham 12 muskets for defense against the threat of nativist rioters, noted Lt. Col. Paul Tanghe, Ph.D., professor of military science at Fordham, at the Nov. 6 event at the Rose Hill campus. Today, the University is home to a military service community comprising “one of the most diverse [ROTC] cadet battalions in the Northeast” and more than 400 students who are veterans, he said, noting the University’s reputation for being welcoming to them.

“The military-connected community is one of the things that makes Fordham special,” he said. “This is a community that’s built around individual paths of service coming together in one place.”

Efforts to honor, support, and grow that community will be part of the yearlong anniversary celebration.

The Office of Military and Veterans’ Services and the Department of Military Science will host two events per month from January through November, with each month’s events organized around a chapter of military history at Fordham. January’s events include a service project—in partnership with Campus Ministry—related to welcoming immigrants, harking back to the origins of Fordham’s military training in 1848. Events in later months will commemorate the Civil War, Vietnam War, World War I, and other epochs, culminating in a gala to be held in November 2023.

There is also a “military muster” outreach effort to Fordham’s military community—ROTC graduates, student and alumni veterans, faculty and staff who served, and friends and family of Fordham veterans—to reengage them with the University. In addition, the veterans’ services office will lead an effort to raise $4.2 million to support ROTC cadets and student veterans as part of Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, the University’s $350 million fundraising campaign.

The veterans’ services campaign received some impromptu support at the Nov. 6 event, which celebrated two distinguished alumni veterans as well as the ROTC program and student-veteran community at Fordham.

Two Who Served with Valor

Attendees included alumni, student veterans, and cadets in Fordham’s ROTC program, a flagship program in the Northeast comprising cadets who attend 17 New York-area schools, from New York University to the Parsons School of Design, Tanghe said.

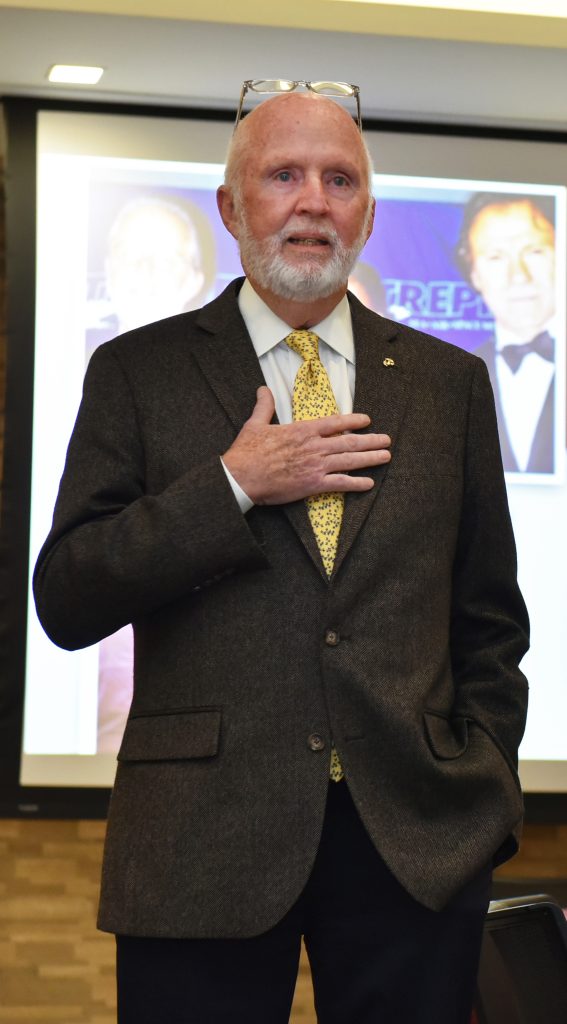

Two alumni veterans were inducted into the Fordham University Military Hall of Fame: William E. Kotas, FCRH ’69, a graduate of Fordham’s ROTC program, onetime U.S. Army captain, and Vietnam War veteran, who was honored posthumously; and retired U.S. Marine Corps Capt. Gerry Byrne, FCRH ’66, a Vietnam War veteran, media executive, community leader, and entrepreneur.

Kotas, who died last year, served as a platoon leader with the 23rd Infantry Division. He was inducted in honor of “the way that he approached all of his duties and obligations to others in his life,” from his cadet years to his post-Army life, Tanghe said.

“His military service was shorter than he wanted it to be because of the manner in which he approached it”—that is, with devotion to the soldiers under his command, Tanghe said.

In a display of that devotion, he personally led a patrol during which he suffered grievous injuries that would require a year of hospitalization and medical retirement from the Army. At the time of his injury, he continued to lead his men and directed them to safety. Kotas received multiple military honors, including the National Defense Service Medal, the Parachute Badge, and the Bronze Star Medal with the “V” device to denote heroism.

Moving back to Nashville, Tennessee, “he continued to find a life of purpose and meaning,” Tanghe said. Kotas was a founding member of the St. Ignatius of Antioch Catholic Church in Nashville and taught in its adult education program on Sundays, among other community activities, and worked for the U.S. Postal Service until his retirement.

Byrne, a 1962 graduate of Fordham Preparatory School, was commissioned via the Marine Corps’ Platoon Leaders Class, which he attended while earning his degree from Fordham College at Rose Hill. He served on active duty from 1966 to 1969, including a tour in Vietnam spanning the latter two years.

“What I learned at Fordham Prep and Fordham College from the Jesuits was ethics and integrity,” he told the gathering. “In the Marine Corps, I learned discipline and leadership. When you combine it, it’s amazing what you get out of it.”

Byrne has had a distinguished career in media, serving as launch publisher of Crain’s New York Business, creator and chairman of NBC’s Quill Awards, and publisher of Variety, leading its transformation into a diversified global media brand. Today he is vice chairman of Penske Media.

He has hosted a Marine Corps birthday celebration in New York City for the past 25 years, and in 2009, he received the Made in New York Award from then-mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Byrne serves on the boards of nonprofits too numerous to name, including the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum. He learned the value of staying busy, he said, from the famed television producer Norman Lear, who, during a conversation about packed schedules, told him that “life is not a rehearsal.”

“When I go back and think about friends and fellow marines who don’t have the ability to stand here like I am, it’s very moving,” said Byrne, who attended the event with some friends from the Corps and his wife, Liz Daly Byrne.

He said he was “extraordinarily honored” to be inducted into the Hall of Fame “and to be a Fordham graduate, and to see … everyone who’s here today.”

A Fundraising Campaign Begins

The fundraising campaign announced at the event has three components:

- An Emergency Relief Fund to promote wellness for military-connected students and provide loans to help students through financial distress ($100,000 goal)

- An endowment to enrich ROTC cadets’ and student veterans’ education by sending them to events and conferences, bringing guest speakers to campus, and providing gear needed for new training opportunities ($1.75 million goal)

- A drive to create a facility at Rose Hill for student veterans and cadets that promotes inclusion, community, collaboration, and information sharing, in part through new digital resources ($2.3 million goal)

Tanghe noted that the Emergency Relief Fund will provide microloans to help students who, for instance, might be unable to meet monthly living expenses on time, because their veterans’ benefit payments are held up by bureaucratic snafus. “If you’re missing a month of rent in New York City, that can be a significant financial burden,” Tanghe said at the Nov. 6 event.

Matthew Butler, PCS ’17, Fordham’s director of military and veterans’ services, said the fundraising effort has gotten off to a strong start, with one donor contributing $25,000 in mid-October.

During a follow-up meeting, the donor wrote another check, for $70,000, Butler said.

That’s when Byrne spoke up—“Liz and I will throw in the other five” needed to bring the tally up to an even $100,000, he said.

Asked later about his spontaneous decision to donate, he gave a simple reason.

“It’s supporting Fordham and veterans,” he said. “There’s no better reason than that.”

Register here to be connected with others in Fordham’s military-affiliated community.

To inquire about supporting the Office of Military and Veterans’ Services fundraising campaign, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, a campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

]]>“Every day you sit through a military science class, every day that you sit through with leaders, who are pouring into you, I suggest you take a few minutes and think about what’s happening. Understand that we’re all tied to something that is huge, and purposeful and you’re tied to a history that dates back to 1775,” he said.

Sullivan, who was invited by Fordham’s Department of Military Science, spent a portion of time talking about the basic functions of the Judge Advocate General’s Corps (JAG), before opening the floor for questions from undergraduates. The division, which is made up of 10,000 civilians and military personnel, is similar to one in the U.S. Navy that captured America’s imagination in the 1992 film A Few Good Men.

Sullivan was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Army in 1993 earned a J.D. from The University of Kansas, School of Law in 1996. He said takes inspiration from

Charles Hamilton Houston, who was the first special counsel for the NAACP. Lawyers, Houston once said, are “either social engineers or parasites on society.”

“I think it’s really applicable to every one of us who wears the uniform; not just lawyers,” he said. “You’re either here to build a country that’s a better place and defend people who are unable in some instances to defend themselves, or you’re in the way.”

Because the Army is so large, he said, those who work for JAG can do everything from working on behalf of the institution itself to supporting individual soldiers in areas such as divorces, consumer protection, and landlord-tenant disputes. There are opportunities to be deployed around the world with different units, and even though all new members spend their first years doing legal assistance and administrative law, it’s customary to branch out into other areas that are applicable in civilian life as well.

“The Army is really committed to making sure you have leaders who are looking out for you. You don’t even get to command a battalion anymore without this really rigorous check on who you are, your background, and the kind of character that you bring to the table,” he said.

Joining the Judge Advocate program is exceedingly difficult, as the Army JAG Corps accepts about 150 to 175 new lawyers out of out 1,500 applicants. Sullivan said that ensures that no one is applying just for a change of career. His advice for standing out? Be amazing at whatever your current job in the Army is.

“What we want are those folks who are the tip of the spear who lean forward,” he said.

“If you’re good at being an infantryman, if you’re good at being a cyber warrior, if you’re good at being a logistician, goodness is always going to eke out. That’s who we want on our team.”

At the March 16 event at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus, Funk spent time with students, answering their questions and discussing his role as the head of TRADOC, which oversees the training of Army forces and the development of operational doctrine for the Army. Funk oversees about 500,000 personnel who conduct all of the Army’s education, training, and doctrinal development, and he is one of the four most senior general officers in the Army, reporting directly to the chief of staff of the Army.

He and the students listened to a livestream event featuring his deputy Lieutenant General Maria Gervais, and the Army’s chief personnel officer, Lieutenant General Gary Brito that addressed the need for cohesive team building.

On the livestream, Funk asked his two lieutenants to share their “Army stories,”—or why they decided to serve—because “nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care.”

Funk broke down some of the topics discussed, including communication, trust, and the need for hardwork with the students.

“Our job is to do hard stuff and connect people,” he told the students. In order to do that, “we’ve got to overcome things.”

He gave the example of Gervais, who he said wanted to be an example for those she commanded, so she goes to the gym every day at 5 a.m. to work on her physical fitness and stay in top shape.

Funk also emphasized how TRADOC has been changing its communication practices to address the needs of their current officers and their loved ones.

“Now when you communicate with families—it used to be we brought them all into the gym, we laid it all out a bunch of powerpoint slides, and then we left—now you’re talking across continents because our soldiers are far and wide—immigrants from all over the place—and we have to communicate with those families,” he said.

Funk emphasized the need for honest and open communication because without it, he said, “they’re not going to follow you.”

The event was organized by Jennifer Alvarez, assistant professor of military science and head of Fordham’s Army ROTC program. It was Fordham’s first joint-event featuring a four-star general in charge of Training and Doctrine Command, which is the branch that oversees ROTC programs.

]]>

In The Gamble, his 2009 book on the Iraq War, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Thomas Ricks described Jack Keane, a retired four-star general, as “crackerjack smart and extremely articulate, often in a blunt way. Most importantly … he is an independent and clear thinker.”

Keane began his military career at Fordham as a cadet in the University’s ROTC program. He graduated in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in accounting and went on to serve as a platoon leader and company commander during the Vietnam War, where he was decorated for valor. A career paratrooper, he rose to command the 101st Airborne Division and the 18th Airborne Corps before he was named vice chief of staff of the Army in 1999.

Since retiring from the military in 2003, Keane has been an influential adviser, often testifying before Congress on matters of foreign policy and national security. In late 2006 and in 2007, he was a key architect of the surge strategy that changed the way the U.S. fought the war in Iraq. He is a trustee fellow at Fordham; a member of the board of directors of General Dynamics, an aerospace and defense company; and chairman of the board of the Institute for the Study of War, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank that monitors global conflicts. He’s also a senior national security analyst on Fox News.

Keane spoke with FORDHAM magazine about service, leadership, and whether or not his loyalties will be divided on Sept. 1, when Fordham football opens its 2017 season with a game against Army at West Point.

What inspired you to join the Army?

I joined the ROTC program essentially because the country was at war and we knew that we would likely be joining it. In the mind of myself and my friends, it made sense to do that as officers, although none of us had ever had a family member who was an officer. Then, as part of the ROTC program, I joined the Pershing Rifles [national military society] because they seemed more confident and accomplished than the other participants in ROTC.

We took basic marksmanship training, and we would go to Camp Smith and practice patrolling techniques and other tactics under the supervision of active-duty officers. That gave me some exposure to what I thought the Army would be like. By the time I graduated, I came to recognize that I had an aptitude for it. And I liked the idea of serving the country.

I saw an interview you did a few years ago with Bill Kristol. You told him about a conversation you had with a Jesuit around the time you were graduating from Fordham. Who was that Jesuit and what did you two talk about?

I think it was Father [Thomas] Doyle, [then an assistant professor of philosophy], but I’m not sure. He asked me what I was planning to do, and I said, “I’m going to go in the Army.” He said, “No, I mean, after the Army.” I said, “Well, I’m thinking about maybe making a career out of it if I’m capable and if I like it to the degree that I think I will.” He said, “Why would you do that? You have so much more to offer.”

I said, “Well, Father, have you ever been associated with the Army? Were you a chaplain?” He said no. I said, “Well, I’ve spent a lot of time around it and people who serve in it, and I don’t think it’s necessarily what you think it is. I think there’s an incredible amount of opportunity for growth and development as a human being. I think I’ll have the freedom of thought and the opportunity to be very challenged, and I think that will lead to a growth experience for me.”

That turned out to be the case.

The way you describe the Army, in terms of opportunities for growth within a strict organizational structure, could also be applied to the Jesuits, I would think. You went to Catholic schools before Fordham, but was Fordham your first encounter with the Jesuits?

I told my new Army friends that after 16 years of Catholic education, the transition to the Army was very smooth! I think of Fordham and the Jesuits as a transformational experience. The rigor of the Jesuit methodology was evident in all classes. What they were least interested in is regurgitation of information. What they’re most interested in is critical thinking based on analysis and some rigorous method of interpretation using reasoning.

That was challenging because it was completely different than my Catholic high school. I thought college was just going to be high school on steroids. At Fordham, it was quite something else. The whole learning process was about your own growth and development as a human being—not just intellectually but also morally and emotionally. I don’t think I would have been as successful as a military officer if my path didn’t go through Fordham University.

Would you talk about your approach to leadership and how it has evolved since your days as a platoon leader? Are there certain qualities that you feel all effective leaders share?

First of all, there are very few natural-born gifted leaders. Most leaders learn from experience. If you’re in the United States military and you start out as a second lieutenant platoon leader with 40 people, your life from that moment on is a leadership laboratory. You have plenty of opportunity to learn and also to observe leaders who are very effective.

When you really get down to it, what you’re doing is motivating and inspiring others to reach their full potential and to do that collectively as an organization. Whether it’s a small team or a large team, the opportunity to learn and to grow is really quite extraordinary.

Some of that for me was in combat, which is such an extraordinary human experience. Everything that you are as a person—your character, your intellect, your moral and physical courage—is brought to bear under significant stress. People’s lives are dependent on you. You’re not only there to protect the civilian population and protect your own soldiers; you’ve been given the authority to take lives. The moral underpinning for something like that is really quite significant. I think having had 16 years of Catholic education and participating at Fordham, where I took four years of theology and four years of philosophy, which were my favorite courses, by the way, really provided me with the wherewithal not only to cope with combat but to perform to a high standard.

With regard to leadership, anybody can make a list of attributes leaders have to have—integrity, judgment, moral underpinning, et cetera. But there is one attribute that’s always stood out for me, and that’s perseverance. You have to persevere to accomplish the mission. Whether that’s in a stressful situation like combat or in other environments, perseverance really can be very defining because there are constant impediments and obstacles. You see people, not just in the military but in all walks of life, who because of those obstacles and impediments accept something less. They could continue to drive on. Most of the time, it’s more about mental toughness than it is about physical toughness.

Two years ago, Fordham ROTC established the General Jack Keane Outstanding Leader Award, to be given each year to a graduating cadet. What does that award mean to you, and what advice do you give newly commissioned officers?

I was honored to give out the first General Jack Keane Award [at the University Church in 2015]. And I was quite humbled by it, to be frank, when I got my head around the fact that they will always give this award to somebody who is outstanding as a cadet and likely more outstanding than I was.

I’ve always told my officers and my generals that we’re in leadership positions because we know how to lead effective organizations; we get results. But our legacy is not how well we run these organizations, because there’s another guy or gal standing behind us who could run it even better. The real legacy is the growth and development of the people in these organizations. If you focus on their growth and development, and if you have programs that support that, the organization will take care of itself. The organization will actually blossom because the people in it are so committed to it and have a very high degree of satisfaction. That is your legacy.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

It came from a sergeant major. I was a major at the time. I was very intense, working very hard, and I was a little frustrated with my boss, my battalion commander, who wasn’t paying attention to all the things I thought he should be paying attention to. The sergeant major closed my office door and said to me, “Major, I know you’ve got some things that are bothering you. I want you to know just one thing: You’re responsible for your own morale.” He looked at me and said, “You got it, sir?” I said, “I got it, sergeant major, thank you very much.”

I never forgot that. It was sound advice.

Fordham football is playing Army at West Point on September first. Who will you be rooting for?

I’m going to miss the game, unfortunately, but good Lord, I want to beat those guys. When I go to West Point for the game, I usually talk to the corps of cadets about the U.S. global security challenges: the Middle East, Russia, the problems with Al Qaeda and ISIS, et cetera. After I spoke a couple of years ago, the first question I got was from a cadet. He said, “General, so we understand you went to Fordham University. You spent almost 40 years in the Army, and you spent only four years at Fordham, so I’m assuming you’re rooting for Army.”

He was just having fun with me, but I looked at him. I said, “Are you kidding me? You know damn well who I’m rooting for tomorrow, OK? I’m rooting for my alma mater.”

So yes, I want both teams to play well, certainly, but I definitely want us to win.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Ryan Stellabotte.

]]>

I was in the Pentagon on 9/11 and lost 85 teammates from the Army Headquarters (among the 125 people killed in the Pentagon and the 59 passengers who died on Flight 77), including a dear friend, Lt. Gen. Timothy J. Maude, a three-star general. My secretary lost five friends she had known for more than 20 years. We sent a general officer to every funeral. Terry, my wife, and I attended scores of funerals. Most were buried in Arlington, all together at a site selected in view of the Pentagon.

On that fateful day, I was in my office when one of my staff rushed in to turn on the TV and advise me something terrible had happened in New York City. I saw that a plane had hit the World Trade Center (WTC). I am a born and raised New Yorker. I noticed it was a blue-sky day and you could not hit the WTC by accident. I knew in 1993 terrorists had tried to bomb the WTC and bring it down from an underground parking garage. I knew instinctively it had to be a terrorist attack and said as much. I ordered the Army Operations Center (AOC) to be brought up to full manning (which was fortuitous because many who occupied it came from the blast area where the plane would eventually hit the Pentagon). The Pentagon is five stories high and five stories below ground level. It houses on a normal day about 25,000 people, most of them civilians. Up until the time the Sears Tower was built in Chicago, it was the largest office building in the U.S. The AOC was on the lowest floor.

We watched the second plane hit the WTC. My operations officer, a two-star general, called me to confirm that the AOC was fully manned. He also advised me that he was monitoring FAA communications. All planes were being grounded, he said, but a plane that took off from Washington, D.C., had turned around in the vicinity of Ohio and approached D.C. from the south along I-95 before turning east, short of the city, and then south again. We know now that the terrorist flying that plane likely believed he was too high. The general and I were discussing procedures for evacuating buildings in D.C. when the plane hit us. My office shook violently and eventually began to fill with smoke. I asked the general if he felt the impact. He said no (he was five stories down under the ground floor). I told him we were just hit and advised him to tell the U.S. Army around the world what happened and that, given the status of the AOC, which was unharmed, we would still maintain command and control of the Army. I told my immediate staff to call home and to evacuate. I kept my executive officer, a colonel, and my aide, a major, with me. I gave them my shirts from my office bathroom, and we soaked them in water and wrapped them around our nose and mouth and headed toward the blast site.

We were about a hundred yards away when the smoke became thicker. People were running from the blast area, and we were ensuring that everyone was getting out. At some point, my executive officer tapped my shoulder and said: “Sir, I think we need to leave this to others and go to the AOC and take command of the Army.” Of course I knew immediately that he was right, and we joined my staff in the AOC. As other officers joined us who were outside the building, we noticed that their shirts were full of blood; some had used their ties as tourniquets to assist the wounded.

We heard the report that five planes inbound to the U.S. were unaccounted for and that fighter aircraft were mustered to engage them. Vice President Cheney had given permission to shoot them down if necessary. I can remember thinking, what must be going through the mind of the pilots knowing they would kill hundreds of innocent people to save thousands. Fortunately, the pilots made visual contact with the airplanes and eventually radio contact, and all five planes were safe. The AOC has very large screens, floor to ceiling, where we monitored activities. The Secretary of the Army was taken by helicopter to our classified alternate site. He did not want to go, but he had no choice.

That night, before I visited the wounded in the hospitals in D.C. and Virginia at about 11 p.m., I told my officers that the Pentagon and the WTC represented the first battle of a new war. “The days of treating terrorists as criminals and bringing them in to the justice system are over. Today’s attack is an act of war, as all terrorist attacks are. The Army will bear the brunt of this fight, and we intend to go find them and we will kill and destroy them by the thousands.” We took one step toward the enemy that night by putting a work plan together to support CENTCOM, who we knew would be in charge of the war. I ordered the 82nd Airborne from Fort Bragg to secure the Pentagon. They were there when people came to work.

We visited five hospitals, seeing all the wounded. The worst had horrific burns. We heard stories of extraordinary heroism. We saw the first responders, many who never left, even though another shift had come on. They told me that because it was the Pentagon, so many of the wounded were initially treated by military people who are trained to treat injuries. In many cases, the bleeding had been stopped, and the wounded were being treated for shock when they arrived. The first responders indicated that lives were saved as a result. Some of the wounded would stay in the hospital for weeks.

The next day, we knew we had a number of people killed because they were unaccounted for. The Army team in the Pentagon showed up for work, on time, mostly civilians. I was so proud of them as I traveled the building to provide reassurance. They knew we were at war and they were a part of something much larger than self. I also knew as I spoke to survivors that many were hurting mentally and emotionally. I ordered the Army surgeon to bring doctors and counselors over to the building to help our folks cope. I also told the Army chief historian to document what took place, it’s part of our history now, and also to record the heroism that took place. When appropriate, I said, we would recognize those involved.

I visited the crash site on 9/12 with the chief engineer, and what I saw was quite remarkable. The upper floors at the plane’s point of entry had collapsed due to the blast and heat from the fire. The Pentagon is actually five independent rings separated by an alley between each ring. The plane entered at the ground floor, knocking down outside lampposts on the approach, and penetrated three of the five rings, with the nose of the aircraft penetrating the inner wall of the third ring. I was looking at what appeared to be a blackened multistory parking garage. I asked, “Where are all the desks, the computers, the walls, the plane?” He said all was consumed in the fire of the jet fuel, likely 2,000-degree heat. He showed me the strut of the plane which held the front tires, and it was in the alley between the third and fourth wing. The whole fuselage had entered the building but nothing was left. I realized that our dead teammates and the remains of the passengers were all around us and had been consumed by the fire.

We ordered the Old Guard, 3rd Infantry from Fort Myer, to the site. They are infantry soldiers. They would come with body bags, and when the fire department recovery teams spotted remains, we asked that all work stop. Everyone on site would stand in place. A four-man team of soldiers would move to the remains and recover them to a tent set up in the parking lot where a chaplain prayed over them with a two-man honor guard at attention. After honors, we turned the remains over to the FBI. They were later returned to us and flown by CH47 helicopter to Dover, Delaware, for identification by their families. We were determined to properly honor our dead as we would on any battlefield.

The engineer indicated that we were standing in the first renovated wedge of the Pentagon, which had not been fully reoccupied as all the new furniture had not arrived. Normally 5,000 people would have been working in that part of the building; at the time the plane hit, however, he estimated that only 2,000 people were there. Moreover, when the building was built during World War II, due to the iron shortage, no rebars were used in the cement beams holding up the floors. As part of the renovation, rebars were inserted. As such, the only part of the Pentagon that had iron rebars in the beams was the area where the plane hit, and that part was less than half occupied. He said the rebars held for 45 minutes, allowing people on the upper floors time to get out. If the plane had hit any other wedge containing approximately 5,000 people, the building would have collapsed immediately, and the casualties would have been on the same scale as the WTC or greater.

A few weeks later, we had the most extraordinary award ceremony I ever participated in. We had to create a new medal for civilians wounded in action because they are not authorized to receive the Purple Heart. The Secretary of the Army and I decorated many people that day for heroism and for their wounds, as they represented everyone who was part of the Army team. They were young and old, men and women, soldiers and civilians, officers and enlisted, black and white. Some were in great physical condition; some were not. It reminded me once again that heroism does not have a gender, a race, a religion, a size, or shape. Anyone willing to give up their life for another, acting instantaneously, has all to do with heart and character. This is about true honor. I was so proud to be among them at the largest and most unique award ceremony of my career.

A few days later, I visited Ground Zero as a senior military leader from New York City representing the Department of Defense. The fire chief in charge of the recovery walked me over the WTC complex of smoldering ruins. It was a macabre and overwhelming experience, as we had all witnessed on TV. I attended the mayor’s evening brief on a pier along the Hudson River. I was impressed; it was as organized as any military operations center. The people were steady, firm, and determined. I offered the mayor the assistance of his military, which had been already offered to him on the phone. As I left, with sirens blasting to take me back to my aircraft, there were hundreds of New Yorkers along the West Side Highway cheering and waving American flags. I was proud of my city, its leaders, and its people. I knew we would never be the same again.

—General Jack Keane, a four-star general, completed more than 37 years of public service in December 2003, culminating in his appointment as acting chief of staff and vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army. General Keane is a 1966 graduate of Fordham’s Gabelli School of Business.

]]>“This University has led the way in graduating men and women of strong character” for 175 years, and has “contributed immensely to the fabric of our nation’s history,” said the guest speaker, retired Lt. Gen. Mary Legere, former senior advisor to the secretary of the Army and the Army chief of staff.

Members of this year’s ROTC class—drawn from a number of area universities including Fordham—will enter occupations ranging from finance and intelligence to engineering and infantry.

The General Jack Keane Outstanding Leader Award was bestowed on cadet Esther Kim, GABELLI ’16, one of only 13 women commissioned this year to be chosen for the Army’s armor branch, which, along with infantry, was opened to women in January.

]]>

Between his time in the Army and his banking career, Calero has worked all over the country and the world. But he never lost sight of the Jesuit principles he grew up on.

“I remained somewhat idealistic about what you can do in life,” he says. “I felt banking could be changed to meet the needs of everyone, not just a subset.”

As president and CEO of TIAA-CREF Trust Co. FSB, Calero has been tasked with creating a bank for teachers, academic communities, hospitals, and other service-oriented professionals, offering mortgages and additional products to help them meet their financial needs. “This is really about helping the difference makers,” he says.

That sense of nobility Calero brings to his work is something he encountered both in the military and in his Jesuit education at Fordham.

“There’s just a value system in both,” he says, whether that system is based on the teachings of Jesus Christ or the U.S. Constitution. “There is a cause greater than yourself,” he adds, noting the “values of courage and selfless service that don’t always exist elsewhere.”

Three years into his first contract with the Army, Calero applied for an ROTC scholarship. He got a call from Fordham and was soon studying economics at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, a few miles from where he grew up on 132nd and Broadway.

Calero says he’s grateful for his Fordham education, not only because of what he learned but of how he learned it.

“It’s not just learning basic skills. It really is critical thinking. Well before you learn something, I think the Jesuits teach you why you should know it,” he says. “You become a continuous learner, where you see learning all around you. It doesn’t just start or stop in the classroom. You spend your whole life learning.”

Right after his Fordham graduation, Calero entered the Army again, separating in 1997 as a captain. “I thought that was it,” he said. Then he got a letter after 9/11. He was promoted to major and sent to Pakistan for 14 months.

During his first stint in the Army in the 1980s, he deployed to Honduras after completing Special Forces training and becoming a Green Beret. It was a time when civil wars and revolution wracked that nation’s Central American neighbors. His experiences in the region played a big role, he says, in understanding the Latin American countries where he did business with Citibank in the late 1990s.

“I would go to every Latin American country and assist with business models, and you recognize that every country is different. Some just did not have a middle class. So how do you grow your business model based on the population?” he said, citing one of many challenges.

His banking career also took Calero to Texas (where his son attended a Jesuit high school), Florida, and most recently, Portland, Oregon, where he was executive vice president of community banking for Umpqua Bank. He returned to New York in 2013 with his wife, Nancy, whom he met in the sixth grade, and their three children.

Calero is one of the newest members of Fordham’s President’s Council, a group of professionals and philanthropists who are committed to mentoring Fordham students, funding key initiatives, and raising the University’s profile. Last year, he mentored a Fordham ROTC student who will be commissioned in May and will go on to active duty. He said he “wanted to do more than donate” to the University when he came back to New York because of the sense of service that Fordham helped instill in him long ago.

“Whether I was the Puerto Rican kid from the Upper West Side or the recent vet,” he says, “Fordham has just always been there.”

]]>