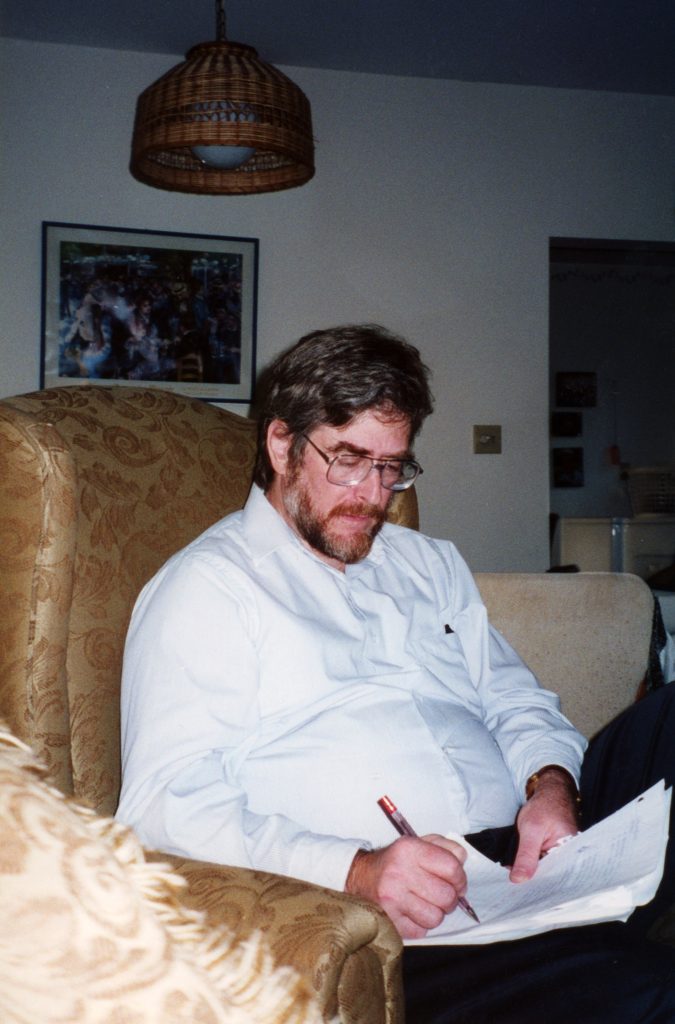

In Trevithick’s undergraduate courses, including Taboo: the Anthropology of the Forbidden and Human Sexuality in Cross-Cultural Perspective, he often revealed how similar humans are in their attractions and aversions.

“We exchanged ideas on which courses might appeal to students and what course names would be most appropriate,” said Anthropology Professor Allan S. Gilbert, Ph.D., the department chair at the time of Trevitheck’s hiring in 2007. Since many of Fordham’s anthropology courses were designed in the 1960s and 1970s, they needed to bring the content and terminology up to date in a way that would also attract students. “Alan was very good at that,” said Gilbert. “He was also an excellent teacher and influenced numerous students to major in anthropology over the years.”

Recent graduate Ellen Sweeney, FCRH ‘23, recalled the compelling discussions she had in two of Trevithick’s classes, even through Zoom during the 2020–2021 academic year.

“I always walked out of his classrooms—virtual and in person—with a smile on my face, musing about all that we had discussed,” she said. “I practically re-taught his lectures to my friends because they were so interesting.”

It may have helped that he often taught his remote classes during the pandemic with his blue parrotlet Giuseppe Celestiano DiForpini—Pino for short—on his shoulder. “Seeing his love for the bird and care for teaching us helped me stay engaged during the semester, and I think it helped me stay on track through that whole difficult year,” said Sweeney.

Born on November 11, 1952, in Washington, D.C., Trevithick was raised by parents who inspired his lifelong intellectual curiosity and wanderlust. His father, John Trevithick, worked for the U.S. mission to the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna, where Trevithick spent several of his childhood years. His mother taught high school and college level English.

Trevithick lived abroad again in his 30s, after earning a bachelor’s in history of religion from George Washington University, a master’s in South Asian studies from the University of Wisconsin, and a Ph.D. in social anthropology from Harvard University. His doctoral research brought him to India for two years as a Fulbright Scholar. It culminated in his research monograph about one of the world’s largest pilgrimage sites, Bodh Gaya.

In the 1990s, Trevithick met his wife, Fordham Mathematics Professor Melkana Brakalova-Trevithick, Ph.D., while the two were teaching at the American University in Bulgaria.

“He just fell in love with the country, and appreciated its complex, ancient history and culture. The Bulgarians are very appreciative of intellectual strengths … and of rich creative inner lives.” Trevithick could relate: he was a musician, an artist, and a writer—he later penned a weekly column for a local Connecticut paper he edited, The Voice, and before he died was hard at work on a comic sci-fi novel, Raise the City, which draws from his Cornish heritage that stretches back to the English inventor of the steam locomotive, Richard Trevithick.

“He was always bubbling with creativity and abilities—whether it was playing jazz on the keyboard, creating paper mâché inspired by mathematical fractals, or spending hours writing his book,” his wife said.

At Fordham, he was instrumental in the unionization efforts for adjunct and contingent faculty. He continued his activism through the Unitarian Universalist Congregation, where he served on their Social Justice Committee.

“His kindness, optimism, and intellect were unmatched,” said Brakalova-Trevithick. “Many people say he was one in a million. I am saying one in infinity.”

Trevithick cherished time with his sons, Joe and Alex, sharing in their pursuits, whether fishing in Connecticut lakes or traveling to the Black Sea. In addition to his wife and sons, Trevithick is survived by his brother, John; daughter-in-law, Kelly; granddaughter, Molly; and many other family members and friends.

A celebration of life service will be held on Nov. 24, at 2 p.m. at the Community Unitarian Universalist Congregation in White Plains, New York, with an option to attend via Zoom. For details, please email [email protected]. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to a charity of your choice or to support the publication of Raise the City.

]]>“They’re writing for the academic audience, but what about us high school students?” asked Suvanni Oates, a high schooler from Bronxdale High School who is an intern for the project. “What about us students who can’t receive that message that they’re trying to send in that way?”

From June 14 through 16, Fordham welcomed 12 scholar-authors from multiple universities alongside local New York City high school students and Fordham undergraduates for a writing workshop where they could all learn from each other.

Creating New Articles—and TikTok Videos

“High school students were introduced to undergraduates [and they are]working with linguistic anthropologists, our authors. We prepared student teams to each read one author’s paper and give feedback on what they understood, what they didn’t understand, what spoke to them,” said Ayala Fader, Ph.D., professor of anthropology at Fordham and founding director of both the Demystifying Language Project and Fordham’s New York Center for Public Anthropology, which is launching next year.

During the workshop, held at the Lincoln Center campus, teams of undergrads and high school students worked with their author to “transpose” previously published articles into two-page digital pieces in language teens can understand. Students even spent a day making TikToks that conveyed the main messages of the articles.

“To hear [the authors’]perspective and actually work with them in person, that was the cool part,” said one of the Bronxdale high schoolers, Athalia McCormack.

The resulting 12 papers will be published as a multimedia open educational resource on the website for Fordham’s New York Center for Public Anthropology.

“Our long-term goals include housing these 12 digital pieces on an interactive website that will be free to use,” said Fader. “We hope that this is going to be a resource for high school teachers to use in existing curricula and also for high school students to experiment with social science, especially linguistic anthropology, which is not part of most curricula in NYC public schools.”

Fordham Students See the Impact

Sitara Vaidy, who graduated from Fordham College at Lincoln Center in May with a psychology and sociology major, was one of the Fordham students working on the project. She said the workshop “allowed the high school students to better understand the significance of fields such as anthropology, sociology, linguistics, etc., and the interesting and important work that they produce.”

Theater and anthropology major Ashira Fischer-Wachspress, FCLC ’23, who also worked with the teams, said she appreciated the justice aspect of the work.

“I am very grateful for the opportunity to have met so many fascinating, driven people working for social justice,” she said.

Expanding into Communities

The DLP is also planning to use the short articles in a summer institute for high school students, where they will study language and power in their own communities. The following summer they plan to host a teacher-training institute.

“By demystifying students’ own experiences with language, the DLP strives to create a grounded, hands-on, potentially life-changing set of social justice tools for high school students and teachers and the faculty and undergraduates who collaborate with them,” Fader said.

The DLP has been externally supported by a Spencer Conference Grant and a Wenner-Gren Workshop Grant. Internal support comes from an Arts and Sciences Dean’s Challenge Grant and Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning, who hosted the pilot project in 2019, and will be collaborating on future programs. Fordham members of the organizing committee include Johanna Quinn, Ph.D. (sociology); Britta Ingebretson, Ph.D. (MLL); and Crystal Colombini, Ph.D. (the Writing Center), who were joined by Mike Mena, Ph.D. (Brooklyn College); Justin Coles, Ph.D. (UMass); Lynnette Arnold, Ph.D. (UMass); Bambi Schieffelin, Ph.D. (NYU), and high school teacher Scott Storm (Harvest Collegiate).

]]>“Academic writing is often inaccessible to the people whom the findings most affect, especially young people of color in public high schools,” said Ayala Fader, Ph.D., project collaborator and professor of anthropology at Fordham. “We hope that this workshop gives students access to scholarship on language and inequality and the ability to reflect on how these subjects affect their own lives, while showing them what college life and careers in linguistic anthropology look like.”

This new writing initiative, the Demystifying Language Project (DLP), began with a three-week pilot class in 2019. In collaboration with Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning, two non-Fordham graduate students taught high school students a class on linguistic anthropology, which included simplified academic readings. But at the end of the pilot session, the DLP team realized the teaching material was still too dense and incomprehensible for the students.

“This is tragic because high school students are losing the potential to better understand the ways that language, culture, and power work in the world,” said Fader, a linguistic anthropologist who studies the relationship between language, culture, and inequality. “During the pandemic, the DLP team decided to focus on creating a set of readings that are accessible to all high school students.”

Fader is collaborating with five other scholars: Sarah Grey, Ph.D., director of Fordham’s linguistics program; Britta Ingebretson, Ph.D, assistant professor of linguistics and Chinese at Fordham; Johanna Quinn, Ph.D., assistant professor of sociology at Fordham; Clarence Ball III, a lecturer in Fordham’s Gabelli School of Business; and Lynnette Arnold, Ph.D., an assistant professor of anthropology at University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Together, they decided to create a three-day workshop, funded by the grant, where traditional roles in the classroom are reversed. Next year, a group of 12 experts in linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics will each select an article they have already published—on topics that are relevant to the students, including police violence, food insecurity, and other inequalities—and work with the students to make the writing more engaging for their high school peers. First, each expert will be paired with a high school student and a Fordham undergraduate who has taken an anthropology or linguistics class; they will review the original article and interview the expert about their work. Then after collaboration with other professionals, each expert will figure out how to distill their work into two pages of simple and interesting prose for a high school student.

“Students will ask the academics about what was interesting and what they didn’t understand, and tell them the most important part about the article from their eyes,” Fader said. “We hope this develops a new way of writing that reaches more people beyond the usual academic audience.”

The revised articles will be published on the American Anthropological Association’s website, where students, teachers, and faculty from other academic institutions can read the material and learn how to integrate it into their own curriculum, said Fader. In addition, the DLP team will publish two pieces: an academic article that documents what it was like to develop and host the workshop and an op-ed that explains their experience in conversational language.

In the months ahead, the DLP team will focus on strengthening relationships with local public high schools in Manhattan and the Bronx. This spring, they will select specific schools to partner with. They will cultivate bonds among all participants so that when the day of the workshop arrives—sometime next year, though the date has yet to be determined—the participants will be ready to collaborate on Fordham’s campus.

“We are potentially creating a set of tools to help high school students make positive changes in their own lives,” said Fader, adding that the DLP team wants to eventually develop a summer institute where more high school students and teachers can learn these same ideas. “This workshop is not only good for students, but also has the potential to transform the field of linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics as more students—both undergrads and high school students—conduct their own research and hopefully become interested in the field.”

]]>Their goal was to emphasize the dangers associated with the unrestricted Web, especially pornography and gender mixing. Rabbinic leaders discussed the internet’s encroachment on ultra-Orthodox Jewish values in an age they dubbed “a crisis of emune (faith).”

Nearly five years later, Ayala Fader, Ph.D., an associate professor of anthropology, sees this challenge in the ultra-Orthodox community as a critical moment of cultural and religious change. She said the internet has amplified existing tensions among the ultra-Orthodox. There is a sense that more and more ultra-Orthodox Jews are leaving their communities or losing faith, but continuing to practice publicly— living what they call “double lives.”

As a result, Fader said, the internet has become a nexus for these concerns, with leadership trying to control its use and those living double lives using it as a lifeline to connect with other religious doubters.

“I don’t know if so many more people are leaving than a decade earlier or if they’re just louder, more public, and more well-organized, but I think there’s a sense in the communities that this is a moment when they need to start thinking about how they’re going to move into the 21st century,” said Fader, author of Mitzvah Girls: Bringing Up the Next Generation of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn (Princeton University Press, 2009)

Fader has been awarded a $50,400 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities for her forthcoming book, Double Life: Faith, Doubt and the internet, which examines the community’s contemporary struggle to define authentic ultra-Orthodoxy.

“I was thrilled to be awarded the fellowship. It will give me sustained time to just focus on writing the book,” said Fader, who has been conducting research on this topic since 2013.

Fader first began the project by connecting with ultra-Orthodox Jews who had, during the mid-2000s, been active on the J-blogosphere, a Jewish blogging community. After interviewing members of various forums and Jewish blogging sites, she learned that the internet gave ultra-Orthodox Jews living double lives an opportunity to explore secular knowledge and activities, like going out together, and learning to bicycle and ski. It also provided a space where they could anonymously critique their communities and their rabbinic leadership.

“There are a lot of reasons that led people to lose faith in the kind of ultra-Orthodoxy they were living,” said Fader, who noted that the community had adapted to other types of technologies in the past—from newspapers and radio to television and books—without as much difficulty. “The internet is problematic because people need to use it for business. You can’t throw out the internet and you can’t keep it out. It’s also easily accessed, privately.”

Watch Ayala Fader discuss the ultra-Orthodox community’s response to “kosher” cellphones.

To better influence their constituency to resist the lure of the internet, many rabbinic leaders are working closely with ultra-Orthodox schools.

“If you don’t agree to sign a contract when your children begin school [pledging]that you won’t have the internet at home, [and]that you won’t have a smartphone, then your kids can be denied access to school,” said Fader. “There are people who have left their communities—not because they didn’t have access to smartphones but because they didn’t feel they could continue to live these kinds of double lives.”

In recent years, there have been a few compromises allowing for some use. In 2013, the cell phone company Rami Levy Communications began selling “kosher smartphones” or rabbi-approved mobile phones that filter and block content considered immoral. Samsung, one of the world’s largest tech companies, debuted its first kosher smartphone specifically for ultra-Orthodox users last year.

Yet, despite efforts to permit some access to the Web, there is still a push to position smartphones as dangerous or contaminating objects, said Fader.

“There is a movement to not carry smartphones out in public, and an effort by educators in particular to create a sense of shame in having them,” said Fader.

She said the constant tug of war between the internet and religion isn’t limited to the ultra-Orthodox faith. It exists in many insular religious communities around the world.

“For religious communities that attempt to control their members’ access to the wider world, the internet is both an incredible tool and a dangerous piece of technology,” she said.

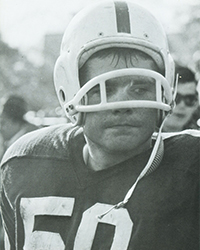

]]>It was 1859 when the first Marrin graduated from what was then known as St. John’s College. Four more generations of the Marrin family would follow him through the Fordham gates, many of them going on to study law or making their mark in other ways, like contributing to the Fordham football tradition celebrated this past weekend.

That’s what Richard Marrin Sr., FCRH ’67, LAW ’70, did, playing under Head Coach Jim Lansing during a pivotal time for Fordham football. His son Richard Marrin Jr., FCRH ’91, LAW ’96, also played for the Rams. He fondly recalls when he and his teammates looked past their own setbacks during the late 1980s to envision the kind of resurgent program Fordham has built in recent years. The Rams achieved a 32-8 record during the past three seasons—fourth best among NCAA FCS teams—and overcame the Penn Quakers, 31-17, on Saturday.

“We knew at the time that our losses, our sacrifices, were a steppingstone,” said Marrin, an attorney who practices in the United Arab Emirates. “We wanted to win, we were used to winning, but we accepted that losing is part of winning, and that someday future Fordham football players would win at the next level. And here we are,” he said.

A Family Legacy Spanning Five Generations

That ethos of striving after a larger—even heroic—ambition is one aspect of Fordham that he thinks has kept his family members coming back to the University over the years. He and his five siblings all graduated from Fordham: Matthew, James, and Peter Marrin, classes of 1996, 1998, and 2000, respectively; Jennifer Marrin Cullinan, Class of 1993; and Margaret Marrin Spencer, Class of 1990, who, like Richard, also graduated from Fordham Law School, in 1993.

Over the years, many members of the Marrin family have been drawn to legal careers, starting with Joseph Marrin, Class of 1859, who apprenticed in the law and worked as an attorney for Fordham in the days before the University even had a law school. His son Wilfrid graduated from Fordham in 1890—after having been a three-year letter winner on the football team—and apprenticed in law before studying engineering at Columbia University and serving as borough engineer for the Bronx.

Wilfrid’s son, Wilfrid Marrin II, Class of 1931, was the first Marrin to graduate from Fordham Law School. He practiced admiralty law in New York, and his two sons, Wilfrid III and Richard Sr., graduated from both Fordham College at Rose Hill and Fordham Law. Richard Marrin Sr.—who died in 2010—first attended the University on a scholarship to play tennis and squash, but he later moved on to football. He was inducted into the Fordham Athletics Hall of Fame in 2002 and would go on to become the namesake of the team’s Rich Marrin Most Valuable Player Award.

“My father was so happy to be part of Lansing’s program,” said Richard Marrin Jr., referring to Jim Lansing, FCRH ’43, a former All-American end for the Rams who would help reestablish the sport at Fordham after a 10-year hiatus. Football was only a club sport when it was brought back to the University in 1964, the year Lansing was hired as head coach. After he led the team to national club championships in 1965 and 1968, the team was elevated to varsity status in 1970, and Lansing joined the Fordham Athletics Hall of Fame in 1976.

Pushing the team on was Fordham’s legacy as a national football power during the days of Vince Lombardi, FCRH ’37, the Seven Blocks of Granite, and sold-out games at the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium. “It was not far from most people’s memory at the time,” Marrin said.

An Education for the Ages

His own time on the football team amplified some of the signature strengths of a Fordham education, like developing self-knowledge. “I was a less-than-stellar player, but I knew I was contributing,” he said. Through the generations, his family has consistently valued this and other aspects of Fordham’s educational philosophy, like promoting ingenuity and innovative thinking and “engaging the people around you with a loving attitude,” he said.

His undergraduate years were filled with novel experiences, like working on an on-campus archaeological dig for a class in anthropology (one of his majors) and joining his fellow student-athletes for occasional dinner and repartee with professors, including Gerard Reedy, S.J., the former Fordham dean who passed away in March.

“They were intelligent, engaging, funny people we had the honor of being invited to dine with as students,” he said. He’s seen this same welcoming attitude among alumni, “and that’s what makes Fordham special for me, that it’s a living thing,” comprising a sort of diverse, worldwide family connected by common values, ready to share some of their time and attention with one another, he said.

Marrin attended Homecoming on Saturday along with his wife, Mona; his brother Matthew and Matthew’s wife, Rachel Marrin, FCRH ’96, GABELLI ’05; his sister Jennifer and her husband, Kevin Cullinan; and his and his siblings’ children.

Richard remembers being taken to Fordham Homecoming games as a child and learning his way around the Rose Hill campus long before he enrolled at the University. Last fall, he came to a football game with his son, then 8, who “looked at the buildings, looked across Eddies Parade towards Keating Hall, and said, ‘It’s just like Hogwarts,’” the wizardry school in the Harry Potter series, Marrin said. “I told him he’s not that wrong, because there’s magic here.”

[In the photo at top, three Marrin siblings—Jennifer, Richard, and Matthew—and their spouses are shown with eight of their children. From left, they are Jimmy, Danny, Christopher, Charlotte, Olivia, Maximus, Lucy, and Sarkis.]

]]>

Daisy Deomampo, PhD, an assistant professor of anthropology, has spent the better part of a decade researching transnational ART and commercial surrogacy. Her forthcoming book, Transnational Reproduction: Race, Kinship, and Commercial Surrogacy in India, is an ethnographic study of commercial ART—including egg donation, in-vitro fertilization, and surrogacy—in India.

On one side of the practice are the commissioning parents who travel to India from all over the world to visit clinics that offer commercial surrogacy arrangements. What primarily draws many of them to India is cost: In the United States, gestational surrogacy can reach sums of $150,000, compared to between $25,000 and $40,000 in India.

On the other side are Indian women who are commissioned as egg donors or surrogate mothers. In the case of gestational surrogacy, an embryo is created through IVF using sperm and egg from the commissioning parents (or third party egg or sperm providers) and then implanted in the surrogate mother’s uterus. She carries the fetus for the nine months of pregnancy, during which she remains under the care of a doctor. Once she gives birth, she gives the baby to the commissioning parents.

On the other side are Indian women who are commissioned as egg donors or surrogate mothers. In the case of gestational surrogacy, an embryo is created through IVF using sperm and egg from the commissioning parents (or third party egg or sperm providers) and then implanted in the surrogate mother’s uterus. She carries the fetus for the nine months of pregnancy, during which she remains under the care of a doctor. Once she gives birth, she gives the baby to the commissioning parents.

These practices raise complex questions about motherhood. Who can be considered the mother in the case of gestational surrogacy? Is it the woman who gestated the fetus and gave birth? The woman who ultimately raises the child? Is it the person who contributes her DNA?

“It challenges our preconceived ideas about basic social categories like the family and motherhood,” she said.

Moreover, Deomampo said, “The dominant discourse in the media suggests this is a win-win situation for everyone involved—in the end the intended parents get their baby, and the surrogate earns much-needed income. But as an anthropologist, I know that human experiences are more complex than that. And the trope of the ‘win-win situation’ only conceals the inequalities embedded in transnational surrogacy.”

The questionable ethics of surrogacy

By 2008, when Deomampo first traveled to Mumbai for her research, India had become a global hub for commercial surrogacy. However, the industry operated within murky legal and ethical waters, and was deeply misunderstood.

For one thing, surrogacy can be dangerous, Deomampo said. In addition to the normal risks associated with pregnancy, the women undergo hormonal treatments for which the long-term consequences are unknown. Nearly all of the women give birth via caesarean section, which is a riskier form of childbirth.

“The industry is not regulated, and there’s no one keeping track of how many times women donate eggs or become surrogates,” Deomampo said.

Photo by Joanna Mercuri

Even though surrogate mothers can earn up to $6,000 per pregnancy—an ample figure for many of the families that Deomampo met—the sum is rarely enough to free families from the poverty that often drives them to surrogacy. For instance, in order to have the full amount needed to purchase a home, Deomampo said, one surrogate had to sell some of her family jewelry.

Even the promise of financial relief—however brief—is complex, said Deomampo.

“Some women saw it as an opportunity and felt it was life-changing—they were providing a service and they were making good money,” she said. “But other women felt it was a degrading experience. They were subjected to a host of medical interventions they didn’t feel comfortable with, and very few ever met the parents who were going to take the babies.”

Surrogacy and race

As an anthropologist, Deomampo is particularly curious about the impact that transnational commercial surrogacy has on racialization—the process of ascribing a racial identity to an individual or a group. In cases in which non-Indian parents pay an Indian woman to carry their child, then, how do they make sense of their connections with each other? How does racialization function in these relationships, especially in light of the fact that commissioning parents and surrogates rarely meet?

“The different people involved tend to rely on these racial constructions to justify why they’re participating in surrogacy and why it exists . . . Race keeps everyone neatly separated,” Deomampo said. “But the construction of race is a dynamic process. It’s not fixed . . . and it’s inherent to the unequal relations at the heart of transnational surrogacy.”

]]>That was the conclusion of research by Emily Rosenbaum, Ph.D., professor of sociology, whose report on home ownership was published in March by the Russell Sage Foundation and Brown University as part of the US2010 project.

Homeownership, in fact, saw a dramatic decrease for certain groups, between 2001 and 2011, according to Rosenbaum’s report, “Home Ownership’s Wild Ride, 2001-2011.

Between the housing-market collapse and the Great Recession, Rosenbaum found that Generations X and Y are homeowners at a lower rate than their older cohorts were at the same stage of life. In addition, Black households experienced lower rates of homeownership than their White counterparts.

Homeownership among lower income and less educated households also experienced a hit, widening the gap between the high and low socioeconomic households.

“We haven’t seen a drop in the overall home ownership rate this large since the Great Depression,” Rosenbaum wrote. “Losses were particularly large among black households, less-educated households, and households in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution. The unequal pattern of loss considerably widened the ownership gaps between black and white households, highly educated and less-educated, and high- and low-income households.”

It was also noteworthy, Rosenbaum said, that those same groups did not participate in the surge in home ownership during the first half of the decade. Low-income households, black households and non-college-degree households saw “little change” in ownership between 2001 and 2005.

“In contrast, increases of two, three, or four points typified the experience of households headed by college graduates, non-black households, and households in the top 20 percent of the income distribution,” Rosenbaum wrote.

Rosenbaum’s findings are based on six years of data from the March Current Population Survey (CPS; 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011), capturing the periods immediately before and after the housing bubble’s burst. The full US2010 policy brief can be downloaded here:http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Projects/Reports.htm

– Jenny Hirsch