Alexander van Tulleken, MD, the Helen Hamlyn Senior Fellow at Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA), has seen firsthand the determination and also the suffering of those who have left behind everything they have ever known or had in order to seek a better future.

With his twin brother Chris, who is also a doctor, Dr. van Tulleken spent two weeks in early January visiting camps, border crossings, and medical clinics to understand the conditions and medical problems the migrants face.

Their journey through Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Germany, and France was documented by BBC1 television in a film titled Frontline Doctors: Winter Migrant Crisis, which aired in the UK earlier this month.

At a screening of the film at the Lincoln Center campus on March 15, Dr. van Tulleken recalled that though he’s worked in a number of humanitarian crises, this one hit him particularly hard.

“On multiple occasions I was reduced to tears. I think it was the most complicated and complex—the worst situation I’ve even seen,” he said.

As depicted in the film, the absence of large-scale government management—with the exception of Germany—has led to squalid conditions in some camps, exemplified by “The Jungle” of Calais, France, where migrants lacked basic hygiene, sanitation, or access to clean water.

Volunteers and charities have mainly shouldered the responsibility for humanitarian aid, as have medical organizations such as Doctors of the World and Doctors without Borders, both organizations whose members have treated numerous cases of frostbite, hypothermia, and respiratory and other serious illnesses.

Dr. van Tulleken acknowledges, however, that more needs to be done than just address the medical problems.

“It seems to me that we all do very badly in the world when we have a million people who are prevented from achieving their potential and when we have hundreds of thousands of children who can’t be educated,” he said.

“Real humanitarianism involves finding dignified ways of helping them to lead full, rich lives the way that we’d want to.”

In the film, Dr. van Tulleken speaks with a man in a registration camp in Greece who left for Europe with his wife and four children when he realized there was no longer any future for them in Syria.

His oldest child, 10-year-old Amna, recalls her life in Syria as filled with the constant fear of missile strikes. Later, breaking into a smile, she also expresses her hopes for an education in Germany and her dreams of becoming a doctor.

Despite terrible conditions and the closing of borders, waves of migrants continue to seek refuge in Europe, and Dr. van Tulleken believes acceptance and aid are the only humane responses.

“We have to find a way of letting large numbers of refugees and migrants into Europe and getting them jobs and housing and looked after. I don’t see any alternative,” he said.

-Nina Heidig

]]>

What happens when a global health crisis leaves the Western media spotlight?

As he watched a patient he’d grown close to die at one of Mother Teresa’s homes for the terminally ill in Kolkata, Joseph Woodring, DO, FCRH ’98, felt overwhelmed by his inability to help the man—and he had an epiphany. “I’d been holding his hand, watching his chest rise and fall,” said Woodring, who first visited India in 1995 as an undergraduate in Fordham’s Global Outreach program. On that trip, he learned to connect with suffering and honor the human dignity of sick and impoverished people. But now, a few years out of college, he wanted to examine the bigger picture. “If I don’t get upstream and learn what these guys have,” he thought, “I’m not fixing anything. I want to be able to actually treat people.”

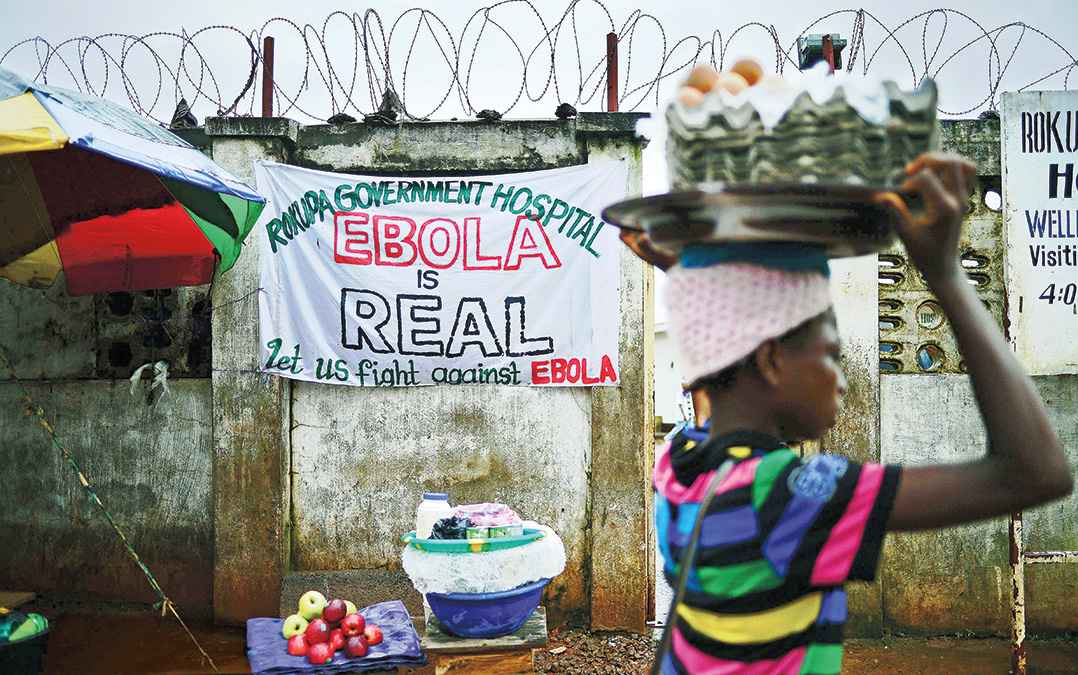

Last year, during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, Woodring deployed to Liberia as an epidemiologist for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. His job was to trace the spread of the virus and work with local people to arrest the contagion. By showing respect for the dignity and self-determination of people in the villages, he said, he was able to convince communities to adopt practices that stopped the spread of Ebola.

That kind of community-minded approach is still needed to fuel social and economic recovery in the Ebola zone and prepare for the next disaster, said Ellie Frazier, GSAS ’15. A recent graduate of Fordham’s master’s degree program in international political economy and development, Frazier was in Sierra Leone in June 2014, studying the role paralegals play in knitting the nation back together after its civil war, when Ebola emerged as a major problem.

Now back in New York, Frazier, an adjunct instructor at Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, stresses that recovering from the outbreak will require sustained international attention and sincere collaboration with affected communities. Emergency Ebola treatment centers are being turned into permanent clinics. That’s good, Frazier said, but villages will also have to reintegrate stigmatized Ebola survivors, negotiate what to do with the land of families wiped out by Ebola, find a way to care for and pay school fees for orphaned children, and address other consequences not yet identified.

“The immediate emergency seems to have subsided, but now what? The tendency with media and some humanitarians is OK, done. But for there to be full-on economic recovery, it is going to take a lot of time,” she said, and “it needs to be bottom up.”

The first case of the most recent Ebola outbreak was reported in March 2014 in Guinea. By August, the United Nations Health Agency had labeled the outbreak an international public health emergency, as the disease galloped across Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, swallowing thousands of victims and decimating those nations’ small and dedicated cadre of medical professionals.

More than 11,000 people died. For eight months, the response was left to just two international charities: Doctors Without Borders and Samaritan’s Purse. While they did heroic frontline medical work, they and later arrivals were ill-equipped to halt the spread of the disease. They had a hard time convincing people to stop kissing or shaking hands, and to suspend traditional burial practices that involve washing and caressing the body—expressions of deeply held spiritual beliefs but also certain methods for communicating the disease.

Medical response teams full of foreigners wrapped in bright yellow plastic suits with shields over their faces arrived on trucks in remote villages to remove the bodies of the dead. They were met with resistance and fear. People hid their sick relatives and buried the dead secretly, allowing the disease to blossom.

When he arrived in Liberia in October, Woodring realized a different approach would be necessary. He focused on communicating with people who could effect change. “It’s the village elders that made the impact,” he said, by enforcing quarantines and maintaining the 21-day observation of anyone directly exposed to the disease. “The village elders were at the apex of those societies, and [people]were roaring in and stripping them of their traditional role. We had to go to the elders and work with them. You’d inform traditional healers and give them due deference and tell them, look, this practice is very dangerous.”

Collaborating with local social systems is key, experts say, both for effective containment of diseases and to lay the groundwork for recovery. Thousands of foreign nurses, doctors, and aid workers, among them several Fordham alumni and staff, aided their West African counterparts during the Ebola outbreak. A year later, the disease is nearly abated, and Western media, which fueled hysteria and panic in the United States during the outbreak, has shifted to other crises. But the affected countries are still struggling to recover, and humanitarian experts are studying the Ebola outbreak to learn how the world can respond sooner and better—and even prevent the next disaster.

The solutions are straightforward but terribly difficult to achieve, according to Alexander van Tulleken, MD, senior fellow at Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs. “The next pandemic is prevented by building a world where people are given the opportunity to get educated and thrive,” he said. It might sound trite, but he’s serious. A strong healthcare system, access to education, and a stable civil society are what ultimately protect against disease.

The reason Ebola was so deadly and persistent in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, while cases elsewhere were more quickly contained, has everything to do with the destabilizing effects of war and extreme poverty. “Diseases are opportunists,” Van Tulleken said. “They only thrive in certain climates. Like criminals and terrorists, they look for places where rule of law is broken down.”

With national infrastructure—not just roads but electrical systems, healthcare, communication, and trust in government—broken apart by years of armed conflict and underinvestment, fighting Ebola was especially difficult, said Melissa Labonte, PhD, an associate professor of political science at Fordham, who has studied the region extensively. She said doctors focused on a medical and technical response, but social wounds allowed Ebola to fester, so a social response was also needed to beat it back.

“You can’t go in and just do things. The imperative is to respond, I know, but you have to know what you are doing before you start acting,” Labonte said. “Local knowledge matters. It was undervalued. Once we started to listen to it and value it, things changed for the better.”

Because the virus is strongest at and even after death, people who care for the sick and prepare the deceased for burial are at highest risk for contracting the disease. One sick person could infect dozens of others, as Woodring learned when he traced the root of 65 cases in one rural county to a man who had cared for his Ebola-stricken brother in Monrovia. That man returned home, got sick, and went to a bare-bones clinic. A grandmother from another village cared for him, wiping up vomit and comforting the man as he died overnight. The grandmother returned home and grew ill. Because she was a central and beloved figure in her community, dozens of people attended her funeral, caressing her body, kissing her—and contracting Ebola. Forty-seven of the infected people died, a 72 percent fatality rate.

“Honestly, all our efforts were for naught if we couldn’t control the burial system,” Woodring said. “Even though there is a huge science to Ebola, if you didn’t get people’s respect from the beginning—by offering it—you were just another white guy coming in telling them what to do.” He hopes national governments can harness the training and funding that followed the Ebola crisis to build sustained healthcare systems in the affected countries.

It’s an approach Elin Gursky, GSAS ’13, considers essential. In April, when United Nations Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon named a high-level panel to study the global response to health crises and present a report by the end of the year, Gursky was appointed to the resource group of experts supporting the panel. Broad and deep international cooperation and political will to invest more money in strong public health systems are what’s needed to prevent and counter future disease outbreaks, she said.

“You can bring in experts and surge capacities, but it needs to support, not supplant, local systems,” Gursky said. “It needs to start at the community level.”

When Laura Sida, a pediatric cancer nurse and a graduate student in Fordham’s master’s degree program in humanitarian affairs, arrived in Sierra Leone last spring, she thought she’d be part of a treatment clinic. But the work quickly shifted to disaster recovery. After six months spent helping ministry of health workers improve clinic management and supervising psychological and social support teams for Ebola survivors, Sida said recovering after the disaster is just as crucial for long-term health as responding to the crisis itself. She’s found her master’s thesis topic: the challenges of rebuilding after a disaster.

A particular difficulty in the aftermath of Ebola is that the disease attacks precisely the people who might be relied on to lead a social recovery, she said. “It kills the caretakers, the people who are the most caring and compassionate. So who is left? Ebola clears the household.”

How the countries build back, from the most immediate relationships in villages to the strength of national health systems—and what the international community learns from Ebola—will determine how the next global health crisis plays out. The world isn’t getting any less connected, as the few Ebola cases that emerged in the United States show, and there will inevitably be a next time, Van Tulleken said. “We need to understand that my life and the life of the poorest person in Africa are intimately linked.”

—Eileen Markey, FCRH ’98, is the author of a biography of Maura Clarke, one of the U.S. nuns killed in El Salvador in 1980, to be published next year by Nation Books.

]]>

Last year’s Ebola outbreak may have faded from the headlines, but its economic impacts in West Africa and the troubling questions it raised about response efforts are far from resolved, according to panelists who have visited the African continent.

“We had more than 10,000 people die of Ebola, and Ebola should really be one of the easiest diseases to control,” said Dr. Alexander van Tulleken, the Helen Hamlyn Senior Fellow at Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs.

He was one three panelists at the April 24 event, “’Post-Ebola’ West Africa: Humanitarian Impact, Challenges, and Opportunities.” Van Tulleken described “an international system of pandemic response that doesn’t work,” noting that each Ebola case only generates about one other.

“The virus is not good at transmitting itself,” he said. “When you have one case in a Dallas hospital that led to several other cases of infected nurses, you then see both the lack of competence and the fear that even if we control Ebola—which we sort of managed to do—that a disease with a higher (transmissibility) like bird flu would really threaten the world economy and human life in a very significant way.”

Last year, the political risks and the risks of transmitting Ebola in various places around the world were not centrally managed, he said. The Obama administration’s Ebola “czar” was better qualified to address political risk than the “very small amounts of widespread risk” posed by the outbreak, he said.

The outbreak took a harsh toll on commerce and agriculture in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, said panelist Ellie Frazier, a master’s candidate in the International Political Economy and Development program at Fordham. To illustrate, she pointed to the 2.8 percent drop in U.S. economic growth following the 2008 financial crisis, compared to an Ebola-related drop of 23 percent in Sierra Leone.

Also, response efforts call attention to “governance gaps” and poor access to justice-related services, she said, noting the barriers to women exercising their legal right to own and inherit land.

“You can come in and do an … economic recovery program and disperse seeds, but if your recipients don’t have secure access to land, where are those seeds going to go?”

She also emphasized the need to examine the conditions that allowed Ebola to spread.

In Sierra Leone, the country’s underdevelopment and a limited health infrastructure abetted the spread of the disease, said Ishmeal Alfred Charles, program director with Healey International Relief Foundation/Caritas Freetown in Sierra Leone.

He described his organization’s efforts to promote hand-washing—important because of the country’s lack of running water and a culture that favors touching as a means of expression. Also important was having burial teams dispose of corpses in a more dignified way, rather than simply enclosing them in bags and heaving them into trucks.

The piling of the still-contagious bodies on trucks “created a lot of risk because a lot of people were hiding at night, trying to bury their loved ones, and that created a lot of infection,” he said.

Van Tulleken said Ebola’s “high imaginability factor” was played upon in the news via graphic images, to the detriment of more useful information such as the need for public support of efforts to manage the epidemic in West Africa.

“Risk management is not a rational set of thought processes, it’s an emotional set of thought processes, and the media played on that to get a huge amount of news coverage for several months,” he said.

Held at Fordham Law School, the discussion was jointly hosted by Fordham’s Mellon Faculty Seminar on Humanitarianism, Department of Political Science, and Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs.

]]>

What’s the biggest misconception about the Ebola virus?

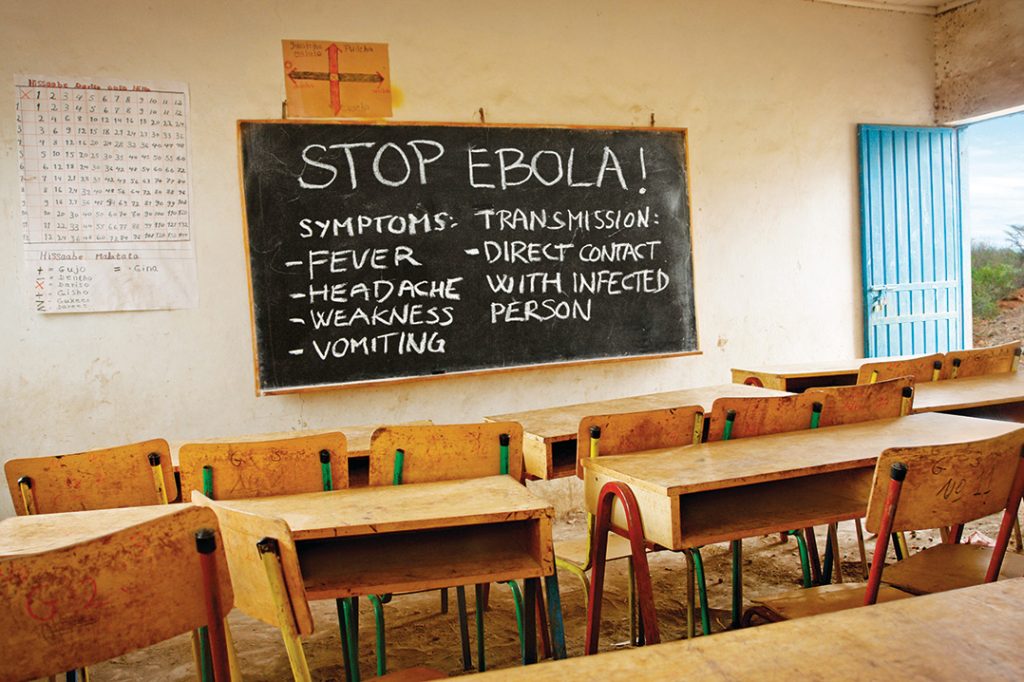

In New York, the biggest misconception is that we’re likely to have an epidemic of Ebola here, or that you can catch it easily. People worry about Ebola because it has a very high case fatality rate. If you catch it, the chances of you dying are about 50 percent. That makes it pretty terrifying. The fact that it spread rapidly in West Africa also makes people think it could spread anywhere. It just isn’t the right kind of virus to do that. It’s actually not very contagious at all. It isn’t spread in an airborne mechanism, like flu. You really need contact with bodily fluids containing the virus.

This outbreak has been confined to Africa and is not expected to present a threat to U.S. citizens. Why should Americans pay attention?

This is killing a lot of people, but it is also destroying health systems. Which means that many more people are going to die of things other than Ebola. If we can’t contain a disease like Ebola, which isn’t that contagious, then it shows how hard it might be to contain something like flu. And if we were talking about flu, I would be saying that New Yorkers should be worried.

Why was it a greater threat to the populations of places like Sierra Leone to begin with, as opposed to the United States?

We’re talking about some of the poorest countries in the world. They’re different from America in almost every way. Many people can’t read and are poorly educated about health. There are a number of other cultural practices that are not helpful. One is the cultural practice of making contact with, and washing, the dead bodies; this sort of thing spreads disease.

Then there are the measures needed to control Ebola, like contact tracing. If we know you’ve got Ebola, we need to get in touch with everyone you’ve been in touch with. In New York, that’s pretty easy. But in West Africa it’s much, much harder. People are afraid of the health services. And many don’t have addresses and don’t have phones.

Does globalization make us more vulnerable to viral outbreaks?

Globalization is an important part of this conversation. We take more planes, there are higher densities of populations, and people move around more. But globalization is also one of the forces in which certain parts of the world have been excluded. We think of globalization as a force for good, and that as certain countries have become richer a rising tide has lifted all boats. In fact, in West Africa that has not been true. There hasn’t been consistent economic growth there for many decades. What we’re seeing now is a disease that’s really a hallmark of poverty and neglect.

Do you think this will serve as a wakeup call for the international community to provide more resources to prevention measures?

This will be a wakeup call in the short term, but the international community has a real problem when it comes to epidemic prevention, because no one ever won a medal for preventing an epidemic. You lose your job if you’re in the business of epidemic prevention, because people say well, there are no epidemics; we don’t need you.

How are relief agencies coping with the different crises around the world, such as Gaza, Syria, the Sudan, Ukraine, and now this?

The timing of the Ebola epidemic is really bad because ordinarily this would have been in the headlines months ago. When people started to say to the media that they’ve been reporting on this very poorly, they could for once reasonably say, ‘Look, there have been other things that have been really important. There are wars in Gaza, South Sudan, Syria,’ on and on it goes….

Is there room for optimism about these subjects?

The good news from the Ebola epidemic is that there is an incentive to develop vaccines and treatments, which in the long term will help—I don’t think we’re going to see a useful vaccine in this epidemic though, which I think will run for several months.

What we’re seeing are a group of aid organizations that are struggling to cope, that are poorly funded, and that are increasingly co-opted into political projects. Aid workers have been kidnapped or killed. So humanitarianism as it exists now is in a dangerous position. In the long run, to deal with humanitarian crises will require more training, more professionalism, and more money, and humanitarian organizations [will]require more room to work in a safe way.

Contact: Gina Vergel

(646) 579-9957

[email protected]

An infectious dise

ase specialist and a senior fellow with Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, van Tulleken has appeared on Al Jazeera America, MSNBC’s “Melissa Harris-Perry Show,” and locally, Fox-5 New York, with the same message:

ase specialist and a senior fellow with Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, van Tulleken has appeared on Al Jazeera America, MSNBC’s “Melissa Harris-Perry Show,” and locally, Fox-5 New York, with the same message:

“It’s very hard to catch this virus,” he says of Ebola, of which there is no cure, and causes hemorrhagic fever that kills at least 60 percent of the people it infects in Africa. Ebola spreads through close contact with bodily fluids and blood, meaning it is not spread as easily as airborne influenza or the common cold.

In this interview with New York’s Fox 5, he discussed the Ebola vaccine currently in trials, and also explained that the virus has been in the country for some time with the Center for Disease Control’s research. Watch here:

In this segment with MSNBC’s Melissa Harris-Perry, van Tulleken says that rather than worrying about a vaccine, “what we need to be doing is containing this epidemic in West Africa.” He also says prevention is always underfunded. “What we’re seeing is a failure of the international system to respond to this virus, and this is a virus we should care about for humanitarian reasons. These countries are really neglected, and that’s why it’s spreading.”

Image via NBC News |

Watch both MSNBC segments below, and visit our YouTube page for more media appearances by van Tulleken and other Fordham faculty.

-Gina Vergel

]]>But before he came to Fordham in 2011, van Tulleken also had an active life in broadcast television, as co-host, along with his twin brother Chris, of the show Medicine Men Go Wild, which aired on the Discovery Channel.

Alex and Chris were back in the spotlight last month, as winners of a British Academy of Children’s Television Award for “Factual” programming. They won for Operation Ouch! a 13-part children’s educational television series about the human body that aired on CBBC in October 2012 and ABC Australia in 2013.

Check out their acceptance speech and post-award interview below. Congratulations to the van Tullekens!

—Patrick Verel

Photo by Patrick Verel

Van Tulleken has conducted aid work in Darfur, Russia, Peru and the Congo, and comes to Fordham from the University of Toronto, where he was a senior resident at Massey College.

He earned his medical degree in 2002 at Oxford, and completed a master’s degree in public health in 2009 at Harvard, where he was a Fulbright Scholar.

Van Tulleken attended the IIHA and earned an International Diploma in Humanitarian Assistance in 2005.

“I finished medical school; I worked overseas; and then I did my first mission in Darfur in 2005. By the time I returned, I realized that even as a qualified doctor, I needed more training in the business of delivering aid in camps in war zones.”

In his new role, van Tulleken will focus on four areas:

• teaching undergraduates and mentoring pre-med students;

• teaching graduate students in the IIHA’s master of arts in International Humanitarian Action;

• reaching out to the University community for research possibilities in fields such as economics, anthropology, sociology and history; and

• researching the continuing changes in humanitarian aid, particularly the drive toward professionalizing aid and improving health care in war zones and after natural disasters.

The third area presents a special challenge, he said. In fact, reconciling political and apolitical action is one of the biggest issues facing aid workers.

“In Darfur, there has been no political solution, but along the way there has been an endeavor to feed, clothe and house people in a very temporary, rudimentary way. I’m trying to figure out if those two things can coexist, and how they do,” he said.

“The solution is essentially political, but along the way, you have a very apolitical engagement, where you say, ‘OK, rather than negotiating or taking a side, we’re just going to provide basic healthcare, shelter and food.’ You don’t ever solve the problem doing that, and yet there’s a great need for it.”

Further complicating matters, the professionalization of aid delivery—while nominally positive—comes with its own complications.

“The age of the amateur, which was really great for a long time, becomes problematic when you have an NGO worth half a billion dollars, when you have private security firms doing humanitarian aid work, or when you have an occupying power delivering aid,” he said.

Van Tulleken is well-versed in raising public awareness about global health, having made two documentaries with the BBC on the subject, as well as a series for the Discovery Channel calledMedicine Men Go Wild.

The show, which he made with his twin brother, Chris, sent him from the swamp forests of the Republic of Congo to the Arctic Circle in Russia. He’s well-acquainted with tuberculosis, malaria and HIV, as well as more exotic ailments such as “loa loa filariasis,” also known as the “African eye worm.”

“What really motivates me are people who are so marginalized that they have no access to health care; they have no access to basic services. Within that, I’m very fortunate that there’s a crazy kind of medicine that’s exciting enough for you to watch on network television.”

]]>