Naison, who has been a professor at Fordham since 1970, has had a long career as an educator, historian, and political activist. The collection includes correspondence, photographs, publications, and more that date from 1931 to 2011.

“The placement of my papers in the Brooklyn Historical Society is not only a great honor, it is a way of assuring than the human rights initiatives I participated in, whether at Columbia, at Fordham, or in the Brooklyn and Bronx communities I lived and worked in, will be documented in a form that students and scholars can easily access,” said Naison.

He credits others with helping to initiate and assemble the project. “The idea for preserving this collection came from journalist and author Kevin Powell, who assigned four student interns to the task of organizing papers by theme and persuaded the Brooklyn Historical Society to be their depository. I am very proud to be able to make this modest contribution to historical research on topics of great importance to me.”

To access the collection, visit the Brooklyn Historical Society.

]]>

“African and African American Studies is not merely for Africans or African Americans; African and African American studies are American studies, studies of who we are, who we wish to become,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “It is, I think, a great sin for people who really don’t want to listen to what the African American experience can and must tell us … We have much to learn and much to celebrate.”

Organized by Amir Idris, Ph.D., professor and chair of African and African American Studies, the day began with a panel of founding faculty members who discussed the challenges they faced forming the department in the early days amidst national strife. A group of Bronx African community members later testified to how research conducted by a Fordham professor has helped bring much-needed services to their community. Another panel on emerging scholars on Africa and the African diaspora from across the University debriefed the crowd on their latest research. And Farah Jasmine Griffin, Ph.D., chair of Columbia University’s newly formed African American and African Diaspora Studies, took a comprehensive look at the current challenges and hopes for the future.

By day’s end, Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American Studies, the longest active member of the Department, who joined its faculty in fall 1970, was deeply moved by the panels’ trajectory. He spoke of the value research can have on communities of color.

“It really makes you realize what we’re doing matters,” he said. “It makes a difference.”

Hurdles of Coming into Being

Moderated by Naison, the first panel featured the department’s founding faculty talking about incidents that are fairly well known in the University community, such as the student protests that led to the formation of the department at Rose Hill, when nearly a dozen African-American students refused to leave the office of dean of student affairs until an agreement was reached to create an African American studies curriculum.

Perhaps less known was the concurrent development of the department at the Lincoln Center campus. Three faculty from Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC), Irma Watkins-Owens, Ph.D.; Fawzia Mustafa, Ph.D.; and Selwyn Cudjoe, Ph.D., recalled a department that had to make its way with little funding at the then-brand-new campus.

Cudjoe said it was a student movement that brought black studies to FCLC, adding that students were also very involved in the hiring of the faculty and selecting the courses. He said offerings were limited and students were recruited from Harlem, Bedford Stuyvesant, and the Bronx.

“There was no blueprint for building and sustaining a department like this,” he said.

Mustafa recalled that the formation of the FCLC department took place well before the restructuring that wove together faculty from the two campuses. Not only was the FCLC faculty autonomous from Rose Hill, but the African American studies department was less integrated with more established disciplines at FCLC as well. Resources were thin. Grant writing and fundraising became the only ways to bring some of the great black thinkers to campus. Watkins-Owens recalled relying on the library’s budget to build up the resources on African and African American content—a move that prompted an appreciative thank you note from the librarian for filling in a major gap in the collection. Watkins-Owens concurred with Father McShane on the importance of African American scholarship to all students.

“Black studies are for everyone, although some might try to lessen its importance in the current political climate,” she said.

Watkins-Owens said there is cause for concern for the discipline’s future, which may be reflective of overarching concerns for the survival of the liberal arts generally. She noted that there were more than 600 African American history programs in 2013 and that number has dipped to 361 programs nationwide. She urged “caution, vigilance, and activism.”

Research Affecting Communities

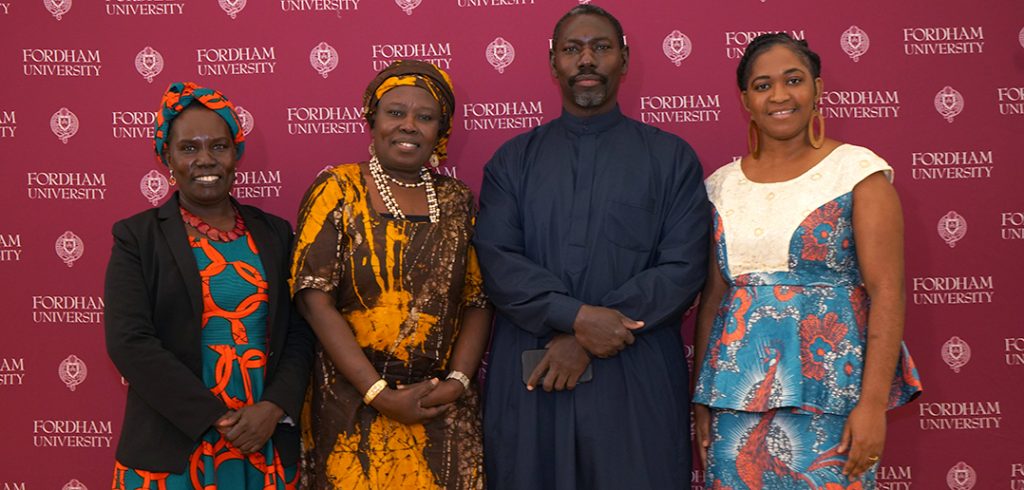

During a panel session with African community leaders from the Bronx, Sudanese native Jane Edward, Ph.D., clinical associate professor, moderated a discussion on how research could be used to help communities, not merely help researchers.

In 2006, Edward joined the Bronx African American History Project to engage the growing community. She and Naison went to events, schools, and organizations, eventually gaining trust. An ethnographer by training, she compiled a list of African establishments that contribute to the vitality of the city, including 19 mosques, 15 churches, 20 businesses, 19 markets, nine restaurants, six hair-braiding salons, six newspapers, four community organizations, two law firms, a women’s organization, a research institute, and a website.

Activist and community leader Ramatu Ahmet recalled how researchers often use her community to grab statements and data then never return to show them the results. Edward returned, again and again, to update the community on her progress, Ahmet said.

Christelle Onwu, a recruitment strategist with the New York City Commission on Human Rights, said that her background in social work helped her appreciate that little can happen on a policy level without good data, which she said Edwards’ paper, “White Paper on African Immigration to the Bronx,” provides.

“To convince an official you need to have numbers,” Onwu said.

“It is very difficult to make change without knowing what the needs are,” she said, noting the importance of research. But, she also warned, “It’s important that [researchers’] subjects don’t feel used, abused, or traumatized.”

To the Future

A forward-looking conversation among emerging scholars of the African diaspora prompted panelist Lauri Lambert, Ph.D., assistant professor of African and African American Studies, to state that she looked forward to when her fellow panelists will be referred to as “established scholars.” It was a fitting precursor to a keynote address delivered by Farah Jasmine Griffin, Ph.D., which examined the current state of the discipline, as well as the outlook for its future.

But first, she started by thanking Fordham for its past and expanded on other significant anniversaries that took place this year, including the 400th anniversary of the 1619 arrival of Africans in the Americas that laid the foundation for slavery in what would become the United States. She noted that while many of the year’s anniversaries were worth commemorating, Fordham’s was worth celebrating.

“This department represents the very best in the tradition of black studies, which through intellectual rigor and its commitment to social justice, seeks to do no less than transform the world,” she said. “And given that you all are one of the oldest and most successful departments you’ve served as inspiration for us at Columbia … [though]we are half a century late.”

She noted that she has been inspired by the work of early Fordham faculty, including writings by Watkins-Owens and Naison. She said that scholarship produced nationwide by African studies has enhanced traditional academic disciplines, especially history, anthropology, sociology. As she looked to the future she cited three sites of engagement for the discipline: in the classroom, in the world, and on the planet.

In focusing on the classroom, she spoke of a variety of contemporary theoretical perspectives including Afro-pessimism (how anti-black violence influences society), Afrofuturism (an Afrocentric intersection of science, history, and technology with utopian visions for the future), black feminism, black queer studies, and black performance studies.

“Now these are oversimplifications of these very rich and complex theories meant only to underscore their robust contribution to the original analyses of black life, culture, history, and the blessed nations,” she said after briefly explaining the theories. “Afrofuturism has been especially attractive to practitioners in technoculture, readers, and writers of science fiction, and some pop culture artists like Janelle Monáe,” she said.

And while she praised the new perspectives and the excitement they bring to students, she also raised concerns that they turn attention away from the dominant continental/European theories that can also serve to frame modern understandings of black life.

“One of the limitations [of the new theories]is the way that such students seem to strongly feel that there is little value outside what this body of work has to offer, resulting in, at best, a failure to appreciate earlier work or, at worst, a dismissal of it as theoretical or old fashioned,” she said.

In the speaking of the world perspective, she noted that few from the discipline were naive about racial progress expected after the election of Barack Obama.

“Nonetheless, in spite of this awareness, few of us, myself included, were prepared for the extent to which the pendulum swung backward in this nation,” she said. “The rise of right-wing, populist nationalism; naked white supremacy; and neo-fascism throughout the Americas, Europe, and Asia has been especially striking.”

When she focused on the planet and the role of Africana studies, she noted that climate change inordinately affects low-income communities of color around the world. She said too few lessons were learned from Hurricane Katrina, as thousands in Puerto Rico and the Bahamas remain devastated from storms there.

She called for a “greening” of Africana studies. “We need more work on the impact of climate change on poor communities and on Island nations, particularly in the Caribbean. And furthermore, we might explore ways that our own institutions can work with these communities on these urgent issues.”

Capping with Culture

While the majority of the day was filled with thoughtful dialogue, the panels and lectures were buttressed by performances of African percussion, singing, and dance by performers from Broadway’s The Lion King. During dinner, one could hear discussions about Muddy Waters coming from one table to Toni Morrison at another and Henry Louis Gates at a third. By the time the cake arrived, DJ Charlie “Hustle” Johnson had pumped up the music to bring the crowd to the floor. The evening was capped by a rap performance by Dayne Carter, FCRH ’15.

]]>

Suffice to say, this iconic short story, “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” penned by the writer Flannery O’Connor, does not end well.

On Saturday, Sept. 28, the story will be performed live at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus.

“Everything That Rises Must Converge: Race & Grace in Flannery O’Connor,” will pair an afternoon symposium with an evening performance of the 1964 story. The event is being hosted by Fordham’s Curran Center for American Catholic Studies, which in May 2018 was awarded a $450,000 grant from the Mary Flannery O’Connor Trust to support programming related to the author.

The day will begin with a panel discussion from 2 to 4 p.m. in Tognino Hall. The panel will be moderated by Curran Center associate director Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, Ph.D., and will feature Rufus Burnett, Ph.D., assistant professor of theology at Fordham; Mark Chapman, Ph.D., associate professor of African American Studies at Fordham; and Karin Coonrod, a lecturer in directing at Yale University.

The symposium will be followed by a performance of the story by international theater troupe Compagnia de’ Colombari directed by Karin Coonrod, to take place in Fordham Prep’s Leonard Theatre at 7 p.m. It will be followed by a conversation with the actors.

O’Connor and Race

O’Donnell, whose forthcoming book Radical Ambivalence: Race in Flannery O’Connor will be published next spring by Fordham University Press, said one of the reasons why this short story is so interesting is that O’Connor doesn’t paint race relations in black and white. Instead, she creates characters who have internal complexity and who act out of mixed motivations. Everyone behaves badly, the ending of the story is tragic, and no one escapes some measure of blame.

In the story, the white woman, who has insisted her son accompany her on the bus since it was integrated, says in her conversations with him that African Americans shouldn’t mix with whites. She nevertheless engages with the son of the black woman when they sit next to them, and when she offers the boy a penny, his mother reacts with deadly fury to the white woman’s condescension.

“I’ve been teaching the story for many years, and it’s gotten more and more challenging to discuss as the years have gone by, as we have a better sense of the tensions and dynamics that govern the relationships between African Americans and whites, both past and present,” she said.

The Myth of ‘White Innocence’

What’s complicated the task, she said, is the fact that while O’Connor possessed an ability—thanks to time spent living in the Northeast and the Midwest—to critique the white supremacy baked into the society in which she was raised, and excelled at writing about the relationship between African Americans and whites, she ultimately ascribes a quality of innocence to the benighted white woman in the story. The woman’s racism is not represented as a virulent force, based in violence and perpetuated by violence, but as a mistaken perspective.

In contrast to this, O’Donnell noted that during the same era O’Connor was writing her story, James Baldwin wrote that racial equality will only be achieved when the myth of “white innocence” is put to rest.

“That’s a concept that we in our time are getting a better handle on, but it’s not a perspective that O’Connor found compelling,” she said.

In fact, O’Donnell argues in her book that despite her best intentions, there are times when O’Connor subconsciously upholds some of the unjust racial practices of the South.

“It’s pretty clear that her sense was that the civil rights movement was very problematic, in part because of the insistence on the part of African Americans that desegregation take place immediately. For O’Connor, as for many white Southerners, the changes were happening too fast and threatened to undermine society. In addition, like most Catholics, O’Connor had a long view of history,” she said.

“[She felt that] you don’t change human nature and you don’t change society overnight by creating new laws. She thought it should be something that happens organically and slowly, and not all at once.”

The story is relevant in 2019, O’Donnell said, because it gives us an opportunity to understand how complex it was to live in that culture and in that time, to understand how fraught it was and how difficult it is for any society to change—a principle that applies to our own current cultural moment.

‘A Powerful Communal Experience’

O’Donnell attended a previous staged production of the story, which takes its dialogue verbatim from O’Connor’s pages. She said the transformation of a story read privately on the page to a drama performed publicly on the stage makes for a powerful communal experience.

“It’s a very interesting experience to witness this play, because as we are watching these characters sitting on the makeshift bus, fighting among themselves, we feel like we are on that bus, too, as it becomes a microcosm of America” she said.

“We are still fighting many of the same battles that we were fighting in 1964; they’re just no longer happening on the bus. They’re happening in other places.”

The event is free and open to the public, though registration is required. To register, visit the Curran Center’s event page.

]]>To honor Fordham’s Bronx connection, the University will host its Second Annual Bronx Celebration Day on Saturday, April 21, with a focus on uniting the diverse cultures within the borough and bringing them together with Fordham and the surrounding communities. The event gives Fordham a chance to get to know its Bronx neighbors while also enjoying local performing artists and vendors.

This fun-filled day will be headlined by Puerto Rican bomba and plena collective Grupo Bámbula, Dominican musicians Yasser Tejada & Palotré, Honduran cultural music group Bodoma Garífuna Cultural Band, Italian percussionist-dancer-singer Alessandra Belloni, and other local Bronx performers. There will also be hip-hop and spoken word performances, Mexican folkloric dance, and more.

Several local artisans will sell original art, and community organizations such as Run for Fun International and the Bronx Children’s Museum will be on hand to discuss their services and offer several ways members of the Fordham community can get involved in life off campus.

And there will be food!

Campus Tours

The community is invited to take campus tours. Fordham has been serving the community for many years, and always looking to increase interaction and personal connections between the on-campus community and neighbors in the surrounding area. To this end, on Bronx Celebration Day, the University invites the community to take tours of the Rose Hill campus.

Register for a FREE Bronx Celebration Day event ticket here. Read our story about last year’s event. For more information, email Natalie Wodniak at [email protected].

Free Jazz Performance after Bronx Celebration Day

That same evening, the University is hosting a jazz concert featuring two of the Bronx’s finest jazz musicians: pianist and composer Valerie Capers and pianist/singer/composer Judy Carmichael. Both of these artists are great personalities and music historians as well as performers and will have great musicians backing them up.

This event is is also free and open to the public. It is sponsored by the Bronx African American History Project and co-sponsored by the Bronx Music Heritage Center. It will take place from 7 to 10 p.m. in the McGinley Center Ballroom. More information here.

]]>

| It was the role that was not meant to be. While waiting for a turn to audition for a film, Joe Morton overheard a famous director berate another actor for “not sounding black.”

Recounting the story to an audience on Dec. 7, Morton, Fordham’s 2012 Denzel Washington Endowed Chair in Theatre, said he decided at that moment that he didn’t care if he got the part. “I said ‘How dare you? What do you know about blackness? How many black people do you know? Do you think the only sound that comes out of our mouths is something Southern, something urban? As many people sitting out there, there are that many kinds of blackness,’’ he said. Morton joined Isaiah Wooden, a doctoral candidate and director/dramaturg at Stanford University, in “Performing Blackness in Space and Time,” a reading and conversation about black identity, career paths, and the politics of representation. The freewheeling conversation with Fordham students and faculty, held at MoBia near the Lincoln Center campus, touched on everything from career paths to the difference between the concepts of darkness and blackness. When one student asked what progress, in terms of blackness, might look like, he suggested progress looks like that event. Morton, whose breakout role was in the 1984 film Brother From Another Planet, spoke of auditioning for roles he knew were meant for white actors. While sounding like “the voice of God” contributed to his professional success, he credited it more to training and a childhood spent overseas with his father, an Army captain. More than anyone, Morton said, his father contributed to his developing an authoritative-sounding voice. When his father died, however, the family was forced to move to New York City, where his voice became more of an impediment than an asset. Attending school with other black children, he said, sometimes led to fights. “I went from Dachau in Germany to 155th Street in Harlem, and I had this voice where no one could tell where I had come from,” he said. “I had done things that they considered ‘white.’ I’d lived in Europe, I dressed differently, my voice was different, and my experiences—while similar in sort of fighting the good fight—were different from theirs.” Reflecting on his semester at Fordham, the veteran actor said it was terrifying at first because it was the first time that he had ever taught a class. In his class, “Creating a Character,” Morton emphasized five questions that each actor has to ask when approaching a role: Who am I? Where am I going? Who do I expect to meet? What do I want? And, To what extent am I willing to go to get what I want? “Everything else in between is what I do instinctually. I then had to explain [that]to 14 students in the classroom. That is where it got prickly, because you don’t want to come across as someone who hasthe answer, because there is no ‘the answer.’ There is an answer, or a series of choices and options you can give them, and that’s what you finally have to come to.” The class became more fun as the semester progressed, he said, and as he and the students became more comfortable. One of their final assignments was doing monologues that students could use for auditions. “I’m hearing feedback from them, things like, ‘Well, I’ve asked all the questions I’m supposed to ask,’” he said. “So they’re actually doing [the]work, which was what I wanted. When they walk out of school, they’ll have a very clear technique of how to approach [acting].” The event was organized by Aimee Cox, Ph.D., assistant professor of performance and African and African American studies, and was sponsored by the African and African American studies department. |

]]>

Photos courtesy of Sandra Arnold

They lie underground, often with no marks to identify them. They’re often interred in out-of-the-way places, hidden from the public. In some cases, their neighbors are the ones they were forced to call “master.”

They are deceased American slaves. And Sandra Arnold wants to find them.

Arnold, a history student in Fordham’s School of Professional and Continuing Studies (PCS), is spearheading the launch of the Burial Database Project of Enslaved African Americans.

Housed in and overseen by the Department of African and African American Studies, where Arnold is also a senior secretary, the project is dedicated to creating a database of enslaved African Americans’ burial grounds in the United States.

Irma Watkins-Owens, Ph.D., associate professor of history and African American studies, serves as co-director with Arnold on the project. The two, along with advisers from the College of William and Mary and Yale and Emory universities, have been developing a website where the public will be invited to submit locations of slave burial grounds around the country.

“The burial grounds of the enslaved are sacred spaces; they mark their place in the world and are a testimony to the humanity of a people denied dignity in life,” said Watkins-Owens. “We must remember, recover and restore these spaces. Doing so is a testimony to our own humanity.”

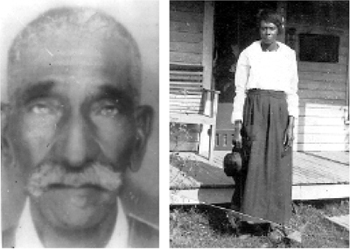

Photo courtesy of Sandra Arnold

The team believes that the database will be a valuable asset to scholars and historians seeking to understand this segment of American history, as well as a tool for genealogical research.

When the website goes live this coming January, in honor of the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, it will be the first project to gather information for a new National Burial Registry of Enslaved African Americans. That registry will officially document the burial grounds, many of which are abandoned or unmarked.

Beyond the value to scholars and researchers, the whereabouts of the sites are important if only for one reason: for the sake of remembrance, said Arnold. Advocacy for remembrance is, in fact, at the heart of the project.

The project’s advisory team includes Michael Blakey, Ph.D., National Endowment for the Humanities Professor of Anthropology and director of the Institute for Historical Biology at the College of William and Mary. Blakey served as scientific director and principal investigator of the New York African Burial Ground Project in lower Manhattan—a project that uncovered the remains of more than 400 Africans buried in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Since many of these grounds are located in rural communities, the project’s participants plan to reach out through historical journals, magazines, churches, and volunteer organizations in order to spread the word.

The project came about when Arnold discovered a plantation cemetery, located in her home state of Tennessee, which contains the graves of her enslaved ancestors. In 2003, Arnold visited the site for the first time, paying homage to the graves of her great-grandfather, B. Harmon, a former slave, and his wife, Ethel. Arnold credits her 99-year-old great-aunt, E. Frye (Harmon’s daughter), for igniting her curiosity to find and visit the site.

“She talked about the cemetery all the time like it was a precious jewel. I just wanted to see it, and then I wanted to see where he was buried. So I went out there, and it was just breathtaking,” she said. “It’s an island in a cotton field, at the end of a field road.”

Arnold began to conduct independent research by collecting data on slave burial grounds throughout the United States. She soon elicited the participation from administrations of four presidential estates: George Washington, Andrew Jackson, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. All contained valuable information on slave cemeteries within their grounds.

“The potential of this project is immeasurable,” Arnold said. “Not only can it properly memorialize the enslaved, it can also facilitate a mutual and respectful dialogue about a subject that is still very sensitive to many.”

She hopes to eventually apply her research on slave burial grounds toward earning a doctoral degree, but there will always be a personal element that runs deep.

“There’s something inhumane about your people lying in unmarked graves and having things built on top of them,” she said. “Not only does it show a lack of respect, it signifies that you weren’t here, you didn’t exist, and you didn’t count.”

]]>

Photo by Gina Vergel

An academic project that started in a small conference room at Rose Hill has expanded into the Bronx, to shed light on one of the largest West African enclaves in the northeastern United States.

“African Immigration Research,” a report released this past August by the Department of African and African-American Studies and the Bronx African-American History Project (BAAHP), details the research of Jane Kani Edward, Ph.D.

A post-doctoral fellow and director of African immigration research in the department, Edward’s research shows the need for educators in the Bronx to develop programs that are sensitive to the children of African immigrants. It also encourages the city Department of Education to address the lack of English-language proficiency among the children of Francophone Africans, and for area colleges to teach the many indigenous languages spoken in the Bronx.

Edward, a Sudanese scholar, came to Fordham in 2006 to conduct oral histories of African immigrants who were revitalizing once-decaying Bronx neighborhoods. These immigrants opened businesses, churches and mosques, bought homes and began using public schools as vehicles of mobility.

A year later, a fire that ripped through a three-family house in the Highbridge section of the Bronx drove her research off-campus. As officials and residents grappled with the tragedy, which killed 10 Malian immigrants—mostly children—hundreds of African Muslims gathered outside a mosque on Sheridan Avenue for a memorial.

Seeing this overwhelming community response, Edward and Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor and chair of African and African-American studies, realized that they would have to go much deeper than conducting oral interviews in Dealy Hall. Edward was brought on full time, and then applied to the Carnegie Corporation of New York for funding.

She and Naison received a $50,000 grant and hit the streets.

“Our objective was to gather the life histories, in detail, of African immigrants,” Edward said. “We needed to build trust, and we did that by going into the community.”

Edward and her research team conducted an average of one interview per week in churches, Islamic centers, schools, businesses and apartments in Morrisania, Highbridge, Tremont, Morris Heights and South Fordham. Most of these immigrants hailed from West Africa—Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, Guinea, Gambia, Senegal and Togo.

By collecting oral histories, Edward hoped to provide insight into the immigrants’ varied life experiences and contributions.

“Africans in the Bronx should not be seen as dependent solely on the social services in this country,” she said. “They are active contributors to the economic, social, cultural, intellectual and political life in the Bronx and their communities in Africa.”

In other words, as opposed to simply assessing the needs and challenges faced by this immigrant community—a time-honored tactic in academic research—Edward set out to analyze their contributions and achievements.

“I also wanted to show that this wasn’t a homogeneous group. They are differentiated by their national, religious, class, social status, gender, age, ability, disability and more,” she said.

Her research team compiled a list of African establishments in the Bronx. It included 19 masajid (mosques), 15 churches, 20 movie rental stores and other businesses, 19 markets, nine restaurants, six hair-braiding salons, six African-owned newspapers, four community organizations, two law firms, a women’s organization, a research institute and a website.

“It shows how they transformed a community,” she said. “They maintain tradition by establishing places of worship and markets that sell the foods they eat.”

Some immigrants go even further in maintaining the traditions of their homeland.

“They send their kids to school in Africa for several reasons. Some consider the schools here unsafe; others don’t want to take a chance on their children not finishing high school,” Edward said. “But they also do it to create a bond between their children and their home country.”

The challenge of disciplining their children, a theme that came up several times in interviews, could be another reason children are sent overseas.

“In African societies, discipline is the responsibility of parents, especially fathers. Here, corporal punishment is against the law and that is a source of frustration for many African immigrants, who fear they are losing control of their children,” Edward said.

Gender role-reversal is another sore spot because, although both immigrant husbands and wives must work in most cases, wives are also expected to cook, clean and raise the children. This can cause a wife to feel overworked. In other cases, a husband may be ambivalent toward his wife if he is forced to pitch in while she is working.

Some of the African immigrants who were interviewed told of frosty race relations with African Americans. Some have been accused of “taking up jobs that were usually done by African Americans,” Edward said.

“Some said African Americans discriminate against them for their dark skin or the way they dress,” she said. “Often, the children will leave the house with traditional dress, such as a hijab (head scarf), but then change before they get to school.”

About 75 percent of the African immigrants are Muslim, Edward said. Therefore, she will focus next on this segment of the population.

“When people in the United States think about Muslims, many think of the Middle East or Southeast Asia. They should get to know their African neighbors to perhaps get a different perspective on Muslims in the United States,” Edward said.

Perhaps the increasing number of African Muslims in the Bronx can provide an example of interfaith dialogue and relations, she added.

“The mosque is not only for their congregation,” Edward said. “A mosque in the Parkchester area of the Bronx, for example, held a huge event to collect donations and funds for victims of the Haiti earthquake and it was well received by the community.”

]]>The segment concerns whether 1520 Sedgwick Avenue—where Kool Herc (Clive Campbell) held his first parties when launching his career as a DJ—was the birthplace of hip hop.

Naison is the principal investigator for the Bronx African American History Project.

]]>Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African-American studies, provided commentary for an upcoming episode in which the show’s hosts attempted to find out if 1520 Sedgwick Ave. in the Bronx was the birthplace of Hip-Hop.

“I had a great time with the crew for this show and am proud we had a chance to showcase the work we do before a national audience,” said Naison, the principal investigator for the University’s Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP).

Naison was interviewed on the Rose Hill campus for an episode set to air in August. Tukufu Zuberi, Ph.D., one of the show’s “detectives” and chair of the sociology department at the University of Pennsylvania, led the interview.

“Professor Tukufu … asked some great questions which gave me a chance to showcase some of the information we have learned in BAAHP oral history interviews,” Naison said. “He asked what the Bronx was like before the 1970s … and what exactly took place in that community center at 1520 Sedgwick that sparked a musical revolution.”

Naison said the segment will feature background and commentary on the conditions that led to the growth of Hip-Hop in the Bronx, including de-industrialization, urban renewal, middle-class flight, drug epidemics, the Vietnam War and arson by apartment owners.

Naison provided the show’s producers with BAAHP photos of the South Bronx before the fires, when it was burning and when President Jimmy Carter toured the area in 1977.

“I definitely had my say over and over again,” Naison said of the two-hour shoot. “Hopefully, some of the more sensible things I said will make it on camera.”

As to whether 1520 Sedgwick Ave. can be referred to as the birthplace of Hip-Hop, Naison says yes.

“This is confirmed by virutally every account of the origins of Bronx Hip-Hop, including the latest memoir by (veteran Hip-Hop deejay) Grandmaster Flash titled, The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash, (Broadway, 2008),” Naison said. “Flash said parties (held at that location) captured his imagination of Bronx youth, and inspired him and other deejays to begin holding parties of their own exciting dancers with pounding beats made from instrumental fragments of records.”

According to the show’s website, History Detectives is devoted to “exploring the complexities of historical mysteries, searching out the facts, myths and conundrums that connect local folklore, family legends and interesting objects.”

Traditional investigative techniques, modern technology and plenty of legwork are the tools the History Detectives team of experts uses to give new—and sometimes shocking—insights into our national history, the site says.

The show airs on WNET-Channel 13 in New York at 9 p.m. on Sunday evenings from June through September. The episode featuring Naison will air in August and October. For other PBS stations, check the program schedule on the PBS website.

]]>HEOP is a New York state-administered initiative created in 1969 that enables students with academic and financial disadvantages to attend college.

HEOP, which is unique in the nation, is open to students of all races and ethnicities. To qualify, students must fall below a college’s general admission criteria and must meet a household low-income standard in the $30,000 to $45,000 range. Accepted students receive financial assistance and comprehensive tutoring.

“Tonight is a reflective time for me,” said Michael Partis, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill (FCRH) graduating with a major in African and African American Studies. Partis said he almost dropped out of Fordham during his freshman year when difficult class work, a part-time job and a broken ankle made the daily rigors of commuting and studying nearly impossible.

“None of us get to one place by ourselves, and I’ve thought about how much Fordham and HEOP have mentored me,” he said. “They’ve kept me focused, and didn’t let me give up on myself.”

The annual senior farewell dinner, held at the McGinley Center, recognized students for their achievement in academics, leadership, motivation, creativity and congeniality. Edlin Rosario was named valedictorian of HEOP’s FCRH class, while Christine Huot received the top honor for HEOP’s College of Business Administration class.

David Stuhr, Ph.D., associate vice president of academic affairs, told the gathering that Fordham’s HEOP program is one of the state’s best, with 97 percent of HEOP students staying on track and graduation rates consistently surpassing state averages. The program services 266 students at Rose Hill.

“Of those four words in HEOP, the one that stands out is opportunity,” Stuhr said. “HEOP has provided you with your lucky chance to excel. But luck is not entirely by accident. It is there to be grasped by those who see it coming their way. Thank you for making Fordham a better place.”

Stephie Mukherjee, director of HEOP at Rose Hill, told the graduating students to “never be without a dream.” She then introduced the HEOP alumni in attendance, many whom have continued their education, including a doctor, lawyer and several associates at investment firms.

“I’m here to show my appreciation for HEOP,” said Steven Nguyen, (FCRH ’97), a change management specialist for Guardian Life Insurance Company of America, who arrived in the United States from Vietnam as a young boy. “My parents worked low-income jobs in a nail salon and it didn’t look like I was going to college. But Fordham’s HEOP accepted me.”

Nguyen then introduced Nga Nguyen (CBA ’06), his younger sister. “HEOP’s a part of our family,” he said.

Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, reiterated the familial nature of HEOP and told the class he hoped they would return to support the students who come after them.

“HEOP is more than an academic program,” he said. “It is the only gathering that has two presidents, three vice presidents, more deans than you can count and a room full of graduates who come back to support their sisters and brothers.

“It captures the genius of the University in a remarkable way,” he added. “No administrator can go through this night without a catch in their throat.”

]]>