That’s what three Fordham students—in two different labs—just spent their summer doing. Working with their professors, they aimed to illuminate various aspects of the replisome, the internal complex that drives the replication of bacteria’s DNA. Their findings could eventually help create innovative antibiotics that target resistant bacteria—a global problem they all cited when applying to the University for their funded summer research.

“It is a very major public health issue,” said one of the students, Sinwoo Hong, noting the “discovery void” within the field of antibiotics that has prompted broad concern.

An Evolving Public Health Threat

Nearly 5 million deaths annually are related to bacteria that have evolved to thwart existing antibiotics, a problem mainly driven by the antibiotics’ misuse and overuse, according to the World Health Organization. The need for new approaches has scientists looking beyond current antibiotics, many of which are designed to disrupt the formation of proteins or the cell wall in an individual bacterium.

One less-explored area? The interplay of proteins that kicks into gear when bacteria replicate their DNA, which “in general is not a major target for current antibiotics,” said Nicholas Sawyer, Ph.D., assistant professor in the chemistry and biochemistry department and research mentor for one of the students.

Hong, a senior biological sciences major on the pre-med track, learned about the problem of antibiotic resistance in one of her classes and was intrigued by the tools available in on-campus labs for examining bacteria. This summer, with a grant from Fordham College at Rose Hill’s summer research program, she worked with Elizabeth Thrall, Ph.D., assistant professor in the chemistry and biochemistry department, on a multiyear project focused on the replisome in Bacillus subtilis, or B. subtilis, a bacterium related to a number of human pathogens.

Moving the Science Forward

Using fluorescence microscopy in a lab at the Rose Hill campus, Hong studied various parts of the replisome and pinpointed the impact of amino acid mutations on bacterial DNA replication.

Another student working with Thrall on B. subtilis in the summer research program, sophomore chemistry major Katrin Klassen, took a different approach—in a project supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, she focused on a protein involved in a replication process that often produces DNA mutations, one way that new strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria emerge.

Thrall and Sawyer are incorporating the work by Hong and another student, Ashley Clemente, into a paper on the synthesis of new DNA, the focus of Thrall’s lab for the past few years. “We’re kind of taking the basic science approach of just learning how this molecular machine functions, and then that may reveal some key interactions that can be specifically targeted,” said Thrall.

She noted another often-cited solution to antibiotic resistance—“we need to use antibiotics judiciously, not for routine use in agriculture or using them to treat viruses.”

In Sawyer’s lab, Clemente, a junior chemistry major whose summer research was supported by Fordham’s Clare Booth Luce program for women in the sciences, experimented with peptides that could inhibit one of the key interactions in the replisome of E. coli. She’s driven by a love for putting chemistry concepts into practice—“When you actually see it in action, it’s truly amazing,” she said.

Serving the Greater Good

Over the summer, Klassen and the other students grew as scientists—“I would not be able to do everything that I’m able to do now without this dedicated time to work on a lot of different experiments,” she said.

Hong particularly enjoyed seeing her work adding to that of past Fordham student researchers. “Seeing all those data compiled and then just looking at the results in the end, it’s very rewarding.”

Clemente drew inspiration from her research’s possible impact. “I love seeing how chemistry can actually be applied,” she said, “and how it can actually help people, and how it can be used for the greater good.”

]]>But what about the birds that are rescued and brought to wildlife rehabilitators? In August 2021, Ar Kornreich, a Fordham biology Ph.D. student who is working on a dissertation about catbirds, began investigating how many of those birds also succumb.

“I knew not all birds die immediately, and I wondered if there had been any research on birds that make it for a while before they die,” said Kornreich, who uses they/their/them pronouns.

“It just seemed like a no-brainer that states should have that info.”

In fact, Kornreich discovered that there is no one place where one can easily access this information. So they filed Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests with eight state agencies tasked with regulating the wildlife rehabilitators. They requested records regarding avian building collision cases between 2016 and 2021. Eventually, they received responses from six states, Washington D.C., and several privately run rehabilitators.

Findings

Kornreich and their co-authors published their results on Aug. 7 in the paper “Rehabilitation outcomes of bird-building collision victims in the Northeastern United States” in the journal PLOS ONE.

They and their co-authors found that of the 3,033 birds that were rescued in these areas, about 60% didn’t ultimately make it: 974 died during treatment, while 861 had to be euthanized. The data also revealed that birds were injured more often during the autumn months, and concussions were the most common injury.

These numbers—and the estimates that can be drawn from them—suggest that bird collision deaths far exceed one billion each year in the U.S., the paper says.

“There’s a huge blind spot in those birds that hit buildings and survive, at least for a little while, and looking at rehabilitation data can help remove that blind spot and help us make more informed decisions about conservation and preventing window collisions for bird populations,” Kornreich said.

There are gaps in the data. The State of New York refused to release the data for all 62 counties in the state, for instance, so Kornreich limited their request to 10 counties in the New York metropolitan region.

The data also came in formats as varied as PDF files and handwritten pages that needed to be painstakingly transcribed. What had initially seemed like an easy project that could be done while the world was on lockdown during the pandemic turned out to be anything but, said Kornreich.

“It was funny; I had to buy the state of Pennsylvania a USB drive so that they could send me all of their data,” they said, laughing.

“I completely underestimated how much work it was going to be.”

Working with a Fordham Grad

To help make sense of the data, Kornreich partnered with Mason Youngblood, a postdoctoral fellow in the Institute for Advanced Computational Science at Stony Brook University. Dustin Partridge, Ph.D., GSAS ‘2020, from the NYC Bird Alliance, and Kaitlyn Parkins, GSAS ’15, from the American Bird Conservancy, served as advisors and co-authored the paper.

Kornreich said they’re hopeful that this research will help wildlife rehabilitation improve their desire and ability to share information. Just as hospital administrators share data on how patients fare after entering their doors, so too should wildlife rehabbers be open, they said.

“There is a very active community of rehabbers who are constantly swapping information and doing their best to make sure that their triage is data-driven and they’re using the most successful treatments,” they said.

“But sometimes the rehab, scientific, and policy community’s transmission of information isn’t the most efficient. Some people in the scientific community look down on rehabbers and say they’re not really making a statistically significant difference, but I think that they are. They’re on the front lines of this crisis, so it is important to get their data and their viewpoints into this conversation.”

]]>How tiny? They’re measured in nanometers, which is one-billionth of a meter. Like the width of a marble compared to the width of the Earth.

By going that small, Koenigsmann and his students have innovated in the areas of biomedical sensors and sustainable energy technology. Now his lab has a new project: scrubbing the air clean of viruses like the one that causes COVID-19.

Preventing Cases of COVID-19

Koenigsmann sees a way to improve on a type of indoor air purifier—activated by ultraviolet light—that destroys particles of coronavirus and other viruses but can also create tiny amounts of toxic byproducts under certain conditions.

Such devices have been around for decades, and were used in hospitals to remove tuberculosis from the air, “so it’s a proven technology,” said Koenigsmann, an associate professor in the chemistry department. “It’s just [that] as it becomes scaled up and more broadly used, and in environments where the air is not tested as regularly, that’s where you can run into problems.”

He and his team are working on new technology that could break down viruses without releasing toxins, which could lead to new types of purifiers that destroy viruses on a greater scale. On a recent summer day, in a lab at the Rose Hill campus, they were getting ready to run experiments using ductwork and a filter containing new types of nanoparticles.

The lab also includes a high-temperature reaction chamber and other tech for making the nanoparticles themselves—indispensable because they’re so small.

Surface Appeal

Koenigsmann, an associate professor in the chemistry department, has long been fascinated with “being able to tune fundamental physical properties” of a substance by changing its size or other aspects.

Break a substance down into smaller units, he explains, and suddenly it’s a lot better at reacting with things, since a lot of small particles will have more total surface area than a few large ones.

How much more? If you’re turning something into nanoparticles, one square meter per gram could become hundreds of square meters per gram. “For the same amount of mass, you gain a tremendous amount of surface area,” he said.

And more surface area means more reactions. For instance, a battery made from nanoparticles offers vastly more internal surface area for conducting an electric current. And air purifiers operating on the same principle offer more surface area for reacting with viruses and churning them up.

Filtering Coronavirus

In some of today’s air purifiers, Koenigsmann said, titanium dioxide chews up a virus particle in a chemical reaction that yields carbon dioxide when it runs its course—but formaldehyde, carbon monoxide, or other toxins when it doesn’t.

To address this problem, Koenigsmann and his team are working on new types of nanomaterials that, because of their size and composition, will fully break down virus particles, giving off only carbon dioxide and opening the door to purifiers that are safe to use more widely.

His undergraduate students contribute a lot to the project—“They’ll tell you things that you wouldn’t have thought of yourself,” he said. “I’m actually learning as my students learn.”

The uses for nanotech seem endless, Koenigsmann said. “The ability to tune things like conductivity, color, catalytic activity, just by making the same material one shape or one size versus another [has] so many possible applications,” he said.

]]>That’s the question driving the summer research of Jackson Saunders, a rising senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill. In a Fordham lab, he’s building chambers to split and direct the flow of sound, pursuing research that could impact not only acoustics but also bulletproofing, rocket design, and more.

Innovative Acoustics

Saunders, a physics and philosophy double major, is working under the guidance of Camelia Prodan, Ph.D., the Kim B. and Stephen E. Bepler Professor of Physics at Fordham. Supported by a summer fellowship from Fordham’s Campion Institute, Saunders is building on Prodan’s research into acoustic techniques inspired by topological materials.

First discovered around 1980, these materials intrigue scientists because of their internal configurations, or topology, that guide electricity into precise streams separated by gaps that block current. A topological insulator, for instance, can channel electricity along its surface but keep it from passing through to the other side.

Since then, scientists have found that such segmented flows can be seen beyond electricity.

Prodan published research in January showing that acoustic materials can be designed to guide the flow of sound in a similar way.

Building Sound Chambers in the Lab

Based on that research, Saunders is building a series of sound chambers that mimic the internal symmetries of topological materials, perfecting a design that will split sound in the same way that topological materials direct electricity into discrete streams.

It’s a project that showcases physics that dates back to Isaac Newton, Saunders said, with the behavior of atoms and electrons being recreated in larger objects like the sound chambers he’s making with a 3D printer.

“We’re taking a very well-studied quantum mechanical effect and realizing it” with classical physics, he said. “What’s novel about what we’re doing is we’re showing that we can create specific applications … using this classical mechanical approach.”

Through the project, he’s helping to build knowledge that could have many uses, from making better soundproofing materials to reducing urban noise pollution to designing rooms that contain all the sound generated within them—even if one side is open.

From Better Bulletproofing to Quantum Computing

Studies of topology-based sound flows could have implications for other innovative materials as well, he said. These could include bulletproof vests that dissipate a bullet’s impact along their surface or a rocket built to channel vibrations along its surface during takeoff without rattling the electronics within.

Topological materials could also be applied in the development of quantum computers that have vastly greater processing power. “Any field that has computation, quantum computing will benefit,” so it’s exciting to be working on questions related to that, no matter how tangentially, Saunders said.

In his research, he has an eye on the past as well as the future. “I’m doing work that is at the leading edge of a 400-year legacy of scientists, and that’s motivating,” he said. “You want to be part of that.”

]]>Lorna Ronald, Ph.D., director of the Office of Prestigious Fellowships, said the students’ early start in the lab, as well as their close collaboration with faculty, were significant factors in receiving the award, which is granted to sophomores and juniors.

“The Goldwater Foundation is looking for students who will become our nation’s leaders in STEM research, so they’re interested in students who have already made an impact, sharing their findings at conferences and in publications,” Ronald said. “Our two Goldwater scholars started undergraduate early and have great mentors. Both Dr. Ipsita Banerjee and Dr. Nicholas Sawyer have worked closely with these students to enable them to produce national quality research as undergraduates.”

Researching Natural ‘Chemo-Targeting Devices’

Biggs’s research explores how proteins (and peptides) can be designed from natural products—or molecules that are produced by living organisms such as bacteria, fungi, fish, mollusks and plants—can be used as “tumor-targeting devices.”

“The goal is to be able to specifically target therapeutics to the tumors, so that it avoids damage to non-cancer cells, and mitigate the side effects that chemotherapy is known for,” said Biggs, a junior majoring in biochemistry.

Biggs and Banerjee grew replica multi-cellular miniature tumors as models in the lab to test their newly designed molecules and examine mechanisms of drug delivery into the tumors. This summer, she’s going to continue her work, this time with ovarian tumors and “other naturally derived cancer targeting molecules.”

“It’s just been wild to be an undergraduate and to have access to these kinds of research opportunities,” she said.

Biggs joined Banerjee’s lab her first year, after going to talk with her about declaring her major.

“She is fantastic,” Banerjee said. “She was always interested in natural product work and the applications of biochemistry and chemistry. She’s a quick learner and one thing I look for in my students is ambition and passion for research. She has the ambition, the motivation, perseverance and she’s very detail oriented.”

The Role of Shapes in Chemistry

Victorio, who will earn one bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Fordham University and a second bachelor’s degree from Columbia University in chemical engineering as a part of Fordham’s 3-2 cooperative program in engineering, was nominated for the Goldwater award through Columbia.

Sawyer said that he and the students in his lab work on developing peptides—short chains of amino acids—that act as treatments and gain access to the cell’s interior.

“What Clara set out to do is help us, as a scientific community, develop a fundamental understanding of how shape plays a role in how peptides enter cells,” he said.

Victorio’s work included an accidental discovery: She set out to take a peptide that had one shape and turn it into a second type of shape, but her work showed that it can actually make a third shape as well.

“It’s really rewarding when a reaction works as expected, because it doesn’t always do that,” she said with a smile. “But, some of the results of the reactions were surprising, and they spun into these whole new avenues.”

Sawyer said that Victorio’s work is at the center of a collaboration with colleagues from the University of Missouri, where they’re continuing to study “where this third shape comes from, and what the factors are that contributed to making that happen.”

]]>A quick glimpse at a readout from the station’s instruments reveals a large spike around 10:23 a.m., followed by smaller spikes until 11 a.m., said Stephen Holler, Ph.D., an associate professor of physics at Fordham, who heads the station, located next to Freeman hall on the Rose Hill campus.

“But overall, this earthquake was a very short and very quick event compared to some of the others that we’ve seen where it seems like it kind of rings for a long time,” said Holler.

He said that although the quake, which struck in Lebanon, New Jersey, rattled residents from Philadelphia to Boston, it was not nearly as bad as other recent quakes.

“The 7.8 magnitude quake in Taiwan—that was 1,000 times more powerful than what we just felt, for perspective. They can get truly scary,” said Holler, whose expert commentary was featured by several media outlets throughout the day. But in the New York region, today’s quake was the largest felt since 2011.

As for aftershocks, Holler said residents need not be worried.

“There may be some aftershocks, which will be the ground resettling down after it slipped, but I don’t expect them to be any larger than what we just experienced,” he said.

The Fordham seismic station, which is operated by the Department of Physics, has been recording earthquakes around the world from the same small building on the Rose Hill campus since 1931. One of the few seismic stations in New York state, it now operates with digital technology.

It’s part of a vast network of monitoring stations that work together to determine data such as the strength and length of the quake, as well as the depth of it. Holler said it’s comparable to the way law enforcement uses data from multiple cell phone towers to pinpoint the location of a single cell phone.

The station has a state-of-the-art broadband seismometer and also houses a strong motion detector under a United States Geological Survey (USGS) program to assess earthquake risk remediation in large metropolitan centers. Data from the station is streamed to the USGS data repository in Boulder, Colorado.

The science of earthquakes has been studied at Fordham since 1910, when the first monitoring facility was constructed in the basement of Cunniffe House.

Rumblings from the offices of the University president apparently disturbed the sensitive instruments, so in 1923, the University constructed a new seismic observatory donated by William Spain and dedicated to the memory of his son William. It was moved several times before finding a permanent home next to Freeman Hall, where the physics department is located.

]]>At roughly 3:15 p.m., the moon will pass directly in front of the sun as part of the first total solar eclipse to happen in the United States since August 2017.

During the 2017 eclipse, the moon covered about 65% of the sun in New York City. This year, the path of totality—where the moon obscures 100% of the sun—will stretch over Syracuse, just 200 miles from New York City. This means the moon will obscure almost all of the sun in the New York City area. The next time an eclipse will happen in the Northeast will be in 2079.

The eclipse will begin around 2:10 p.m. and finish at around 4:36 p.m., but the best time to watch will be from 3:15 to 3:30 p.m.

Robert Duffin, Ph.D., a lecturer of physics who teaches astronomy at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus, said the fact that the eclipse will be happening in the late afternoon means that any open space will suffice for viewing the event.

“You want to be in a wide space so you can see the effects of 85% coverage. It’s going to be dim, and you’re going to see a difference,” he said.

Eclipses play an important role in Duffin’s class; among other things, students learn that more than 2,000 years ago, Aristotle estimated that the diameter of Earth’s shadow at the moon during a partial lunar eclipse was two and a half times the diameter of the Moon. Ancient Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos then determined from observing the umbra (or dark shadow on the surface of the Earth) during a solar eclipse that the Earth’s diameter is about three and a half times the Moon’s diameter.

Here are some great places to catch the eclipse. Remember, never look directly at the sun without protective glasses or other safe viewing methods.

The Bronx

Rose Hill campus

The Fordham Astronomy Club will be set up in the middle of Edwards Parade from 3:15 to 3:45 p.m. The group will use a telescope to project the eclipse onto a screen for safe viewing and also have telescopes set up for the viewing of Jupiter and Saturn, which will be visible during the eclipse. Contact Jackson Saunders at [email protected] for more information.

Wave Hill

The 28-acre estate in Riverdale will be hosting a viewing party from 12 to 5 p.m. Visitors will have the chance to pot seeds, make a festive eclipse party hat or celestial floral headband, enjoy live music and storytime with the Riverdale Library, and see the eclipse with free viewing glasses. Read more.

Manhattan

Umpire Rock, Central Park

The 15-foot-high, 55-foot-wide outcropping just north of Hecksher Playground is the perfect place to take in the show near Midtown Manhattan. Enter the park at West 62nd Street and Columbus Circle.

Pier I, Riverside Park South

Jutting into the Hudson River at West 70th Street, this spot guarantees unobstructed views, with the added bonus of seagulls who might not quite know how to react to the changing light.

American Museum of Natural History

The museum will offer family-friendly educational activities and will give out eclipse glasses while supplies last, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Read more.

Brooklyn

Green-Wood Cemetery

The cemetery will host a free event from 1:30 to 5 p.m. featuring special-edition glasses and telescopes equipped with solar filters. There will also be amateur astronomers to help operate telescopes and answer questions, along with self-guided explorations and artist-led installations. Read more.

]]>“He was a great scientist and a remarkable thinker. He loved every aspect of chemistry,” said his colleague Shahrokh Saba, Ph.D., a current chemistry professor who taught with Clarke for more than four decades. “Even a week or so before he passed, he was asking me to do something related to chemistry for him.”

Clarke served as chair of the chemistry department for six years. His collective research in biochemistry and neurochemistry led to more than 100 published articles and book chapters. Some of his research led to the creation of drug treatments, including one that he personally benefited from when he had a case of shingles. At Fordham, he helped to establish the University’s nuclear magnetic resonance facility, where faculty and students study the molecular structure of substances, said Saba.

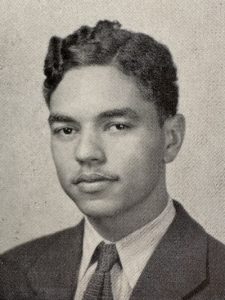

‘I Never Dreamed of the Possibility’

Clarke was born in Kingston, Jamaica, on March 20, 1930, to Izzet Dudley Clarke and Ivy Clarke, née Burrows. He was a “rising star,” said Peter, but it was difficult for him to pursue his passions at home.

In 2017, Clarke spoke to Fordham News about his educational journey.

“I was the eldest of four children and the first in my immediate family to attend high school. There was no university in Jamaica at that time, and my parents couldn’t afford to send me abroad for higher education,” he recalled.

Clarke’s adviser at St. George’s College, a Jesuit high school, reached out to Fordham for help.

The University’s president at the time, Robert Gannon, S.J., offered Clarke a scholarship. He earned his bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1950 and continued at the University as a chemistry department assistant. He went on to complete his master’s degree in 1951 and his Ph.D. in 1955 from Fordham.

“I never dreamed of the possibility of such accomplishments as I was growing up,” Clarke said.

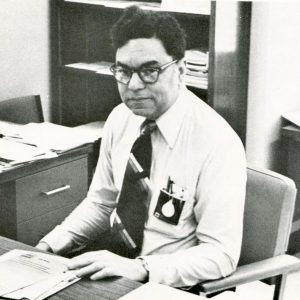

‘A New Life’ as a Chemist and Bronxite

In 1962, he returned to Fordham as an associate professor of chemistry. He was promoted to full professor in 1970, later serving as department chair from 1978 to 1984.

“Don Clarke’s calm, kindly disposition provides an interesting contrast to his fierce love of learning and his intense dedication to his field of biochemistry,” reads his citation from Fordham’s 2022 Convocation, where he received a standing ovation for his longtime service.

Clarke was a fellow of the American Chemical Society, where he also served as chair and councilor of the New York section. Before joining Fordham’s faculty, he held research positions at the University of Toronto, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York Psychiatric Institute, and Columbia University, continuing his work with the Mount Sinai School of Medicine while working at Fordham.

“He was a stream of references, papers, educational techniques, lab procedures, and amazing insight into the fundamentals of academic chemistry,” said Frank Sena, Ph.D., an adjunct professor who first met Clarke when Clarke was a young faculty member and Sena was a chemistry doctoral student. “Very recently when this semester began, I wrote to him expressing how strange it was without him on Thursday afternoons. … [John Mulcahy Hall] will be emptier without him.”

Clarke retired from Fordham last year, concluding nearly 70 years at the University—as both a faculty member and a three-time Ram.

“The fact that he had gotten the president’s scholarship in 1948, there was always [this sense of]payback, I think, on some level,” said his son Peter, adding that Fordham became his father’s second home. “It was the thing that helped him leave Jamaica and start a new life. Fordham treated him well, so he treated Fordham well.”

For more than 50 years, Clarke lived in a Bronx house that was about a mile from the Rose Hill campus, said his son. He walked across Fordham Road to campus every day, carrying his briefcase, until it became difficult for him to walk. (Instead, he took the bus.)

In his spare time, Clarke was an avid puzzle solver who worked on The New York Times crossword puzzle every day, according to his family obituary. He inspired his great-grandchildren to play Sudoku.

Clarke is predeceased by his parents and his wife, Marie Clarke, née Burrowes; daughter Carol Halper; sons Stephen Clarke and Ian Clarke; and daughter-in-law Dawn. He is survived by his children Paula Clarke, David Clarke, Sylvia Clarke, and Peter Clarke; seven grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

A funeral Mass for Clarke was held at the Church of the Holy Spirit in Stamford, Connecticut, on Feb. 29, directly followed by his burial at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. A Fordham memorial service will be held at the University Church on April 6 at 11 a.m., followed by a reception. Gifts in Clarke’s name may be made to Fordham University or the Exchange Club of Stamford.

“The main idea is to identify and understand the different types of biases in these large language models, and the best example is ChatGPT,” said Rahouti. “Our lives are becoming very dependent on [artificial intelligence]. It’s important that we enforce the concept of responsible AI.”

Like humans, large language models like ChatGPT have their own biases, inherited from the content they source information from—newspapers, novels, books, and other published materials written by humans who, often unintentionally, include their own biases in their work.

In their research project, “Ethical and Safety Analysis of Foundational AI Models,” Amin and Rahouti aim to better understand the different types of biases in large language models, focusing on biases against people in the Middle East.

“There are different types of bias: gender, culture, religion, etc., so we need to have clear definitions for what we mean by bias. Next, we need to measure those biases with mathematical modeling. Finally, the third component is real-world application. We need to adapt these measurements and definitions to the Middle Eastern [population],” said Rahouti.

Starting this April, Amin and Rahouti will work on the project with researchers and graduate students from Hamad Bin Khalifa University and Qatar University, both located in Qatar. Among the scholars are three Fordham students: a master’s student in data science, a master’s student in computer science, and an incoming Ph.D. student in computer science. The grant funding will partially support these students.

This research project is funded by a Qatar-based organization that aims to develop Qatar’s research and development, said Amin, but their research results will be useful for any nation that uses artificial intelligence.

“We’re using the Middle Eastern data as a test for our model. And if [it works], it can be used for any other culture or nation,” he said.

Using this data, the researchers aim to teach artificial intelligence how to withhold its biases while interacting with users. Ultimately, their goal is to make AI more objective and safer for humans to use, said Amin.

“Responsible AI is not just responsibly using AI, but also ensuring that the technology itself is responsible,” said Amin, who has previously helped other countries with building artificial intelligence systems. “That is the framework that we’re after—to define it, and continue to build it.”

]]>That’s why Michelle Rufrano, an adjunct sociology professor, decided to plan her upcoming course a little differently this time—by using a new AI tool.

Rufrano is the CEO of CShell Health, a media technology company that aims to curate health information and use it to help create social change. She worked with her business partner, Jean-Ezra Yeung, a data scientist with a master’s in public health, to develop an augmented intelligence tool that can sift through hundreds of thousands of articles of research and synthesize them into various themes.

Rufrano recently used the tool to plan her Coming of Age: Adulthood course at Fordham, sourcing readings from scholarly articles available on PubMed, an online biomedical literature database. The tool organized those articles into knowledge graphs—or geometric visualizations that map out correlations and topics that are most present in the research, without a professor having to manually sort through article titles and abstracts.

According to Rufrano, this method allowed her to plan her curriculum and readings much more efficiently.

“It cuts the research time in half,” Rufrano said. “That kind of document review would usually take me about four months of looking through all of that data. It’s down to about two weeks.”

Rufrano’s course explores the life course theory, which aims to analyze the structural, social, and cultural contexts that shape human behavior from birth to death. As a relatively unique field, Rufrano said it can be challenging to find materials, particularly those that include the most recent research. She said their AI tool is uniquely suited to solve this problem.

“I would have never found some of these studies that came up in the knowledge graphs, because they were published last month, and just would have probably escaped the regular search engines,” Rufrano said. “You would have had to put in some very specific language that you wouldn’t have necessarily known to use.”

Rufrano said it is crucial that students are exposed to a mix of current research in addition to classical works when preparing to enter careers in the field.

“That is so valuable for students who are going into a very volatile workforce. They need to have this very up-to-date information,” she said

Future Uses for the AI Tool

Rufrano and Yeung met while studying for a master’s in public health, and went on to form CShell Health, which uses augmented intelligence to reframe consumer health information and make it more accessible. The course planning model was an early experiment in what they hope will be a total reimagining of public health literacy.

“We can address really salient issues like how institutional discrimination is embedded in language,” Rufrano said. “If we can see the vulnerabilities in the data, then we can correct for the bias in the research. That’s my dream for the company.”

]]>But was that air pollution actually causing those symptoms?

In a new study published this month, Marc Conte, Ph.D., professor of economics at Fordham, says no.

“There’s no question that air pollution is a public health threat, but measuring the impacts of air pollution on humans, whether it’s cognitive ability, physical health, or mental health, is pretty challenging,” said Conte.

Correlation vs. Cause

The challenge, he said, is overcoming the temptation to put more weight behind observational studies than they deserve. A researcher might collect data and determine that a large number of people with dementia have bad teeth. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that bad teeth cause dementia.

“The public health researchers who are conducting this work know that they’re studying correlations, but when the media reports on these studies, the layperson who consumes that information might not necessarily know that it’s a correlation and not causal,” he said.

For the study, “Observational studies generate misleading results about the health effects of air pollution: Evidence from chronic air pollution and COVID-19 outcomes,” which was published in the journal PLOS ONE, Conte and his research partners paired data from two different sources that were collected between March and September 2020.

The first source was health data gathered from U.S. Census tracts in New York City, whose geographic centers are less than 500 meters from a highway. That narrowed the number of tracts studied down to about 800 out of a total of 2,168 in New York City. The researchers then compared that to data collected from the New York City Community Air Survey, a network of 100 air quality monitors maintained around the five boroughs.

That extensive network, which augments a much smaller number of monitors in New York City maintained by the federal government, allowed researchers to compare communities that are downwind from highways with those that are upwind. If poor air quality were responsible for more severe COVID symptoms, communities downwind would be expected to fare worse than their upwind neighbors.

Findings

Conte said that across the 800 census tracts, there was no statistically significant difference between those who were downwind and thus had poorer air quality and those who were upwind and therefore had better air quality. Other factors, such as income differences, access to health care, and the ability to work remotely during the pandemic, are more likely culprits for severe symptoms, he said.

In addition, many residents in these areas were unable to leave New York City at the height of the pandemic, either because they lacked the means to do so, or their jobs required that they work in person. The inability to engage in this kind of “defensive behavior,” resulted in higher exposure to those infected with the virus.

“That fact suggests this issue of environmental justice extends beyond the fact that certain communities are located near more pollution sources,” he said.

“It’s actually a more systemic problem that lower-income people are employed in positions that could not accommodate remote work, with many designated ‘frontline’ workers,” he said, or simply didn’t have the resources to leave the city.

None of this means that researchers should cease conducting observational studies, especially during health emergencies like the pandemic, Conte said. Rather, he hopes the study will further elevate the notion that “correlation does not equal causation” in the public consciousness.

More Data = Better Outcomes

A second takeaway from the study is the importance of maintaining a large network of air quality monitors, which together are able to generate finely detailed data. In fact, Conte’s team also conducted a second experiment on the same topic using only data collected by the seven monitors maintained around New York City by the Environmental Protection Agency, without any input from the New York City Community Air Survey.

The results were much closer to the observational studies that had been done and might have led readers to believe that air pollution and severe COVID symptoms are explicitly linked to each other.

“As we think about things like wildfires and other sources of air pollution, these problems are becoming more and more intense,” said Conte.

“For us to be able to take measures that can reduce the public health outcomes and the threats to public health, we need to have more information. We need to invest more.”

]]>