Father Massaro said he has known of “the prestigious McGinley Chair since I was in my 20s,” in part because of the semiannual public lectures the chair historically delivers.

This tradition, said Massaro, “is one of the ways that Fordham reaches out and plays its role as a center of theology in the broadest, pluralistic circles of New York City life.”

Tracing the Legacy of the McGinley Chair

The McGinley Chair takes its name from Fordham’s 26th president, the Rev. Laurence J. McGinley, S.J., who deepened Fordham’s ties to New York City life and culture by establishing its Lincoln Center campus and serving as a founding director of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Upon McGinley’s retirement in the 1980s, colleagues in New York’s civic and arts communities contributed generously to endow the chair.

As the third person to serve as the McGinley Chair, Father Massaro said he is “very conscious of walking in the footsteps of the first two occupants.” Inaugural chair Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., was the first and still only American theologian to be named a cardinal of the Catholic Church. The second chair, former Vice President for Mission and Ministry at Fordham, Patrick Ryan, S.J., was widely known for his expertise on Islamic political thought and fostered mutual understanding between followers of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He served as the McGinley Chair from 2009 until his retirement in 2022 and now lives at Murray-Weigel Hall, the Jesuit retirement home outside Fordham’s Bronx campus.

Father Massaro, whose area of theological scholarship is social ethics, has written extensively on Catholic social teaching and its recommendations for public policies. He has published 150 articles to date and authored 11 books, including United States Welfare Policy: A Catholic Response (Georgetown University Press, 2007) and Pope Francis as Moral Leader (Paulist Press, 2023).

“A moral theologian like myself is well positioned to hold this chair and to leverage its publicity to address a broader audience,” he said, “one that includes not just people of faith, but people who don’t think often in terms of religious belief or practice.”

A Fresh Take on American Exceptionalism

As part of his installation ceremony, Father Massaro will deliver his first McGinley Chair lecture on Wednesday, April 9, 2025. The topic will be the problematic and ambiguous concept of “American exceptionalism” as seen through a Catholic lens.

“Catholics have hardly ever spoken about this notion of America as inherently unique and morally superior compared to other nations,” said Father Massaro, “leaving a void of perceptive assessments regarding America’s potential contribution to the global pursuit of political values. So I’ll be offering a fresh perspective. This research project has been percolating in my mind for many years now.”

]]>Establishing a multifaith ministry at a Jesuit university is an important move, said Father Judge. It reflects the changing makeup of the University community.

“I think last spring’s protests on campus showed us the need for dialogue and the need to know one another better, and that’s not simply in a religious sense,” he said. “That’s also in a cultural sense and in looking at different worldviews and different issues that are important to us.”

Father Judge comes to Fordham with years of on-campus experience: He first arrived at the Rose Hill campus in the mid-1980s as a Jesuit scholastic to study English and philosophy, and has since worked in leadership roles at a number of Jesuit secondary schools including Fordham Prep. We spoke to him about the work of Campus Ministry and why you don’t need to be religious to seek out the department’s services.

What does the director of Campus Ministry do?

The Office of Campus Ministry at Fordham exists to serve the religious and spiritual needs of our students and our faculty and staff. We have about 12 people on staff, and they range from the music director in the University Church; to the directors of religious life for Catholics, Jews, and Muslims; to people who do spiritual direction; to people who run service programs. And then we have a bunch of student interns who help them do all that. Our goal is to make a lot of things available to people so that they continue their religious observance while they’re away from home, but also we give them outlets for developing and deepening their spirituality and finding opportunities to learn through service work.

You have said you believe that Jesuit spirituality can animate everything we do at Fordham. Could you explain what you mean?

A keystone of Ignatian spirituality is…that God is to be found in all things. So I think that’s why Jesuits historically have been missionaries and historically why Ignatius was drawn to the big cities where there’s lots going on and lots of people coming together. There are opportunities for us to find God in new arrangements and new places and new ways. I think that’s at the heart of what we do as a university.

For a student at Fordham who is not religious, what does Campus Ministry offer?

For anybody, we offer a willing ear. There are always pastoral crises, whether or not you think you need a pastoral response to them. People have family members who’ll get ill…They have relationships that go sour, they have goals they’re trying to figure out. So we try always to be a willing ear, whether that’s from a religious perspective or just a listening perspective.

What programming are you most excited about this year?

I think what I’m really excited about is looking at how Jewish life and Muslim life start functioning on campus. It’s been fun finding non-Christian spaces for them to worship in and learning about those things ourselves. We just built our first sukkah on the Rose Hill campus for [the Jewish]Feast of Sukkot, so that’s been a lot of fun. The department itself is engaged in a strategic planning process to look at how this multifaith ministry changes us and how it changes … the programs we offer. I’m very grateful that Fordham has the resources and the will to make this kind of investment in our students.

Campus Ministry Events and Service Opportunities:

For upcoming Campus Ministry events at Rose Hill and Lincoln Center, and to volunteer with community partners, visit the department website here. You can also follow Campus Ministry on Instagram and on LinkedIn for events and news.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

]]>Environmental themes can clearly be seen in scripture, and not just in an incidental way, said Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., professor emerita of theology. That’s the message of her new book, Come, Have Breakfast: Meditations on God and the Earth, published earlier this year by Orbis Books.

“This isn’t just [one] point in the Bible,” Sister Johnson said, “it runs through everything—Genesis and the Psalms and the prophets and the Wisdom literature and … into the very last book of the New Testament. You could trace this theme all the way through.” Her book is replete with examples, including these four:

Having Dominion over Nature Doesn’t Mean What You Think.

The biblical passage about God giving humans “dominion … over all the wild animals of the earth” has been taken to justify domination and exploitation of nature, which is “not even remotely” correct, Johnson writes. Rather, in biblical contexts, dominion means good governance—as practiced, for instance, by a stand-in who oversees part of a king’s realm and carries out his will. In Genesis, God is entrusting humanity with wise stewardship of nature, “a responsible service of protection and care,” according to Johnson.

Animals belong to God, and “the Creator is not a throwaway God,” she said. “It’s like anyone who creates anything. You don’t want it to be ruined.”

The Bible Puts Humans in Their Place.

Christian thought and prayer have often treated nature as a “stage set” for the story of God’s relationship with humanity, Johnson writes. But the Bible often paints a different picture, as in Psalm 104, a lengthy paean to the greatness of God’s creation. It glorifies everything from the sun and the moon to Earth’s landscapes and its variety of life, including humanity in the mix. “We’re in the middle, and we’re part of this community,” rather than being at the apex, Johnson said. But “in no way does this deny human distinctiveness” and our special capacities and obligations, she writes.

Animals Have God’s Ear Too.

“Scripture is threaded with verses that depict animals giving glory to God,” Johnson writes. As St. Augustine described it, she said, animals “are giving praise because they’re reflecting the goodness of the Creator.”

Indeed, during the Great Flood in the Book of Genesis, God establishes a covenant with not only Noah but also “every living creature” aboard his ark. “It precedes the covenants with Abraham, Moses, David, and the one established by Jesus,” Johnson writes. “It is never revoked.”

Jesus Valued Nature.

Raised as an observant Jew, Jesus was steeped in the creation theology of the Jewish religious tradition, Johnson writes. He viewed nature with fondness and wonder and speaks of its intrinsic value: In the Gospel of Matthew he speaks of “the lilies of the field” that “neither toil nor spin” yet are clothed in glory, as well as “birds of the air” who “neither sow nor reap” yet are cared for by God nonetheless.

“Pope Francis calls it the gaze of Jesus—like, how did Jesus look on the natural world?” Johnson said. “That gaze is what we should be trying to emulate.”

]]>Tonight, the Jewish members of our community and their families and friends will gather around their dinner tables for a festive meal to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Many will dip apple slices into honey or eat yehi ratsones (symbolic appetizers), laugh, reminisce, and look ahead. Rosh Hashanah invites introspection and celebrates the creation of the world. It also opens the Days of Awe, traditionally a period of intense soul-searching leading up to Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement and the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, when we fast for 25 hours and reflect on our fragility and morality to hopefully become more open-hearted, loving, and connected.

To me, Rosh Hashanah means decorating my home with pomegranates, shared meals, and an expectant hush going through the synagogue as the cantor raises her voice for morning prayers. Every year, I feel myself sink anew into this wall of words and sounds—and always the shofar, the ram’s horn, this ancient instrument whose sharp voice seems to peer straight into my heart, reaching me where words cannot. The shofar stirs my soul and reminds me that the time has come to make amends and to reconnect with the divine, with those around me and myself. This poem by Shoshanah Tornberg captures what the shofar can mean.

Hearing the shofar is so central to Rosh Hashanah that in 2020, when we could not be together, local synagogues organized a communal shofar blowing ritual on Broadway that reached all the way from 64th Street to Columbia University on 116th Street. At almost every corner, young and old gathered around a shofar blower, often with tears in their eyes and giddy with excitement, to hear the shofar and to feel the holiday.

This year, almost a year after October 7, this may feel particularly difficult. There are still hostages remaining in a now destroyed Gaza, the suffering of innocent Israelis and Palestinians is ongoing without an end in sight, and elections are looming here in the United States. A lot of hurt and anger may have accumulated. And yet my hope for all of us is that we can, if only over the bread we break, or the moments of the shofar, connect to whatever is that matters in our lives so we may be agents of healing and peace in our communities.

Shanah tovah umetukah, anyada buena, dulse i alegre—may we have a good, sweet, and happy New Year.

Rabbi Katja Vehlow, Ph.D.

Director of Jewish Life, Campus Ministry

Dear President Tetlow; Father Rector; professors, staff, and students; dear friends,

The page of the Gospel that has just been proclaimed is part of the itinerary of Jesus toward Jerusalem, which unfolds as a succession of teachings and recommendations.

The question posed by John: “We saw someone driving out demons in your name, and we tried to prevent him because he does not follow us,” describes well the rigid pattern within which they, like us, would like to imprison the freedom of the Spirit, who always blows where and how he wills.

It is interesting to note that in the previous passage the disciples divided themselves from each other in the name of their individual “I.” Here they separate from others in the name of their collective “we.” One’s own name, whether individual or collective, is the principle of division; only the “Name,” only the “Name,” which is the name of Jesus, is a source of unity among all.

We all know that he who loves enjoys the good of others, while the egoist does not enjoy the good, but only his own possession, and hurts the good of others. Egoism produces suffering proportional to suffering. Through it, death entered the world.

Selfishness, envy and pride can have both the personal and collective forms. The latter, much more harmful, can grow so vast and apparent that it turns invisible to the individual, who can continue to live by dedication, service, and humility towards his “we”—like a bandit remains loyal to the gang.

Our true unity is to go after Him, who leads us out of all fences and opens us to others, starting with the most distant and excluded. Being with Him, the Son, unites us to the Father and to our brothers and sisters, and forms a “we” that is not confined by a hedge of ownership, but driven by an internal drive of sympathy towards all.

In the name of Jesus, the church embraces everyone and excludes no one. This means that no one in the church can remain anonymous—that is, without, or even worse, not in Jesus’ name, and consequently without knowledge of him. In other names, personal or collective, ghettos, partisan spirits, sects and exclusions are born.

But he who excludes one, excludes Him who has made himself the last of all. In doing so, he fails to be Catholic, universal, and even Christian: He does not yet have the Spirit of the Son who, knowing the Father’s love, died for all brothers and sisters.

The stronger our union with Him, the stronger the unity among us. This unity in full freedom—our our own and that of others.

The disciples form a community, a “we,” which is the church. Yet, the church does not have its centre in itself. It does not take a census to feel strong, nor does it seek its own glory. It serves only the Lord, and is open to all, with willingness and humility.

As long as it seeks unity in Him, it is one and remains free, liberating and Catholic. However, it must always beware of collective pride, typical of the weak that becomes gregarious. This is how divisions arise among believers who consider themselves better and more faithful to the truth, thinking they have God with them.

We Christians are not the masters of salvation, given to us by Christ. Although we have different responsibilities or better vocations within the church, we Christians only have the task of making the person of Christ encounter, among ourselves and others, through our witness, our word, and our actions.

As Christians we are called to follow the example, the teaching and the generosity of Jesus, who assures at that the simplest deed done for Him or His Kingdom will not go unrewarded even if it is as simple and natural as giving a glass of water to someone who is thirsty.

Unfortunately, too often we behave like the Apostles in this passage—we are less generous than our Lord. We are less generous than our Lord. Even worse, our one concern becomes the hoarding of the grace of God, refusing to give freely what we received freely. Sometimes, we even envy the good done by others, as if their good deeds diminish our own or make us appear less virtuous. Our duty as Christians is to extend to others the grace we have received and to encourage the good that is being done, regardless of whether we receive credit for it.

There is a latin proverb that says: bonum diffusivum est sui, that is, goodness spreads itself. God, in His nature, shines with goodness, and spreads goodness. He is always surrounding us with signs of His love, always seeking to fill our hearts with wisdom, grace, mercy, and virtue.

But if Jesus is so generous, why do we so often fail to experience His generosity? If God’s goodness is like the sun, shining brightly and constantly all around us, why do we so often find ourselves in darkness, sadness, and difficulty?

Often, we fail to see God’s light shining in our lives, because we don’t bother to open the shutters. It can be a bright, beautiful day outside, but if we lock ourselves up in our room behind closed shutters and drawn curtains, we will not benefit from the light.

God is respectful of our freedom. He wants our friendship, not blind obedience. He gives us countless opportunities and instruments to receive His generous grace, but He does not force us to use them. He gives us the Sacred Scriptures, the gift of prayer, the sacraments of the Eucharist and Confession, each one of which is a flowing fountain of grace and spiritual strength—but it is up to us to come frequently and drink deeply from this spring.

Dear friends, God is generous, and His infinite generosity calls for openness and unity, including within the Fordham community. On your website, one can read that one of your core principles is to care for others. The Gospel reminds us not to hinder those who do good in His name and to stay vigilant over our own hearts. The Holy Spirit desires welcoming communities, and Fordham, as a Catholic university following the Jesuit traditions in this city of New York, is uniquely positioned to appreciate and foster the creativity with which God acts.

As we experience God’s generosity in this Holy Mass, let us therefore thank Him from the bottom of our hearts and seek the grace and courage to open the shutters of our souls, embracing openness and support.

Nothing would please Him more. Amen.

]]>In 1965, there were an estimated 60,000 Catholic priests living in the United States. By 2022, that number had dropped to around 35,000, even as the country’s population had grown by 100 million.

In a new documentary, Discerning the Call: Change in the American Priesthood, two Fordham students seek to explain why.

“Today, there are not as many men joining [the priesthood], and they join later,” said rising junior Jay Doherty, the film’s co-director.

“There are all sorts of different changes that have impacted the church and vocational discernment, and we wanted to tell the story of those changes through the lens of American history,” Doherty said.

Doherty, who majors in digital technologies and emerging media and philosophy, directed the film along with Patrick Cullihan, FCRH ’24, a fellow Duffy Fellow at Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture. They conducted 30 hours of interviews with 27 priests, many of them residents of Fordham’s Jesuit communities. The film debuted in April at a Fordham Center on Religion and Culture event at the Howard Gilman Theater in Manhattan and is now available online.

High-profile Catholic leaders such as Cardinal Timothy Dolan and James Martin, S.J., editor at large at America magazine, make appearances, as does Fordham faculty member Bryan Massingale, S.T.D.

A Culture Long Gone

Cardinal Dolan spoke about how, in the years leading up to and during World War II, a strong “Catholic culture” made the vocation much more common than it is now. Catholics were born in their own hospitals, lived in predominantly Catholic neighborhoods, attended their own schools, and married other Catholics.

“With the collapse of the Catholic culture, that kind of external prop and encouragement to priestly vocations would have gone,” he said.

Dolan, who himself entered the seminary right out of high school, said that means fewer men are taking that path as teenagers.

“Now, the decision to become a priest would not be something imposed from the outside. It would not be something that would just be expected. It’s something that is a radical choice,” he said.

The priesthood has also been attracting more men who identify as theologically orthodox; the filmmakers note that a recent survey found the percentage of priests who identify as such increased from 20% in 1970 to 85% in 2020.

Stricter Requirements

Father Martin noted that one of the changes that affected recruitment into the Society of Jesus was stricter entrance requirements implemented in the 1960s. That resulted in fewer men joining, which some church leaders have welcomed, as it means those who do are more committed.

For the church to grow, though, Martin said leadership might have to also come from those in the pews.

“I think that the Holy Spirit might be calling lay people to a more active participation in the church,” he said in the film.

A Complex Issue

Father Massingale noted that many incorrectly assume the decline can be pinned on the church’s requirement that priests remain celibate.

“That’s certainly the case for a given segment, but it’s never been a complete explanation for all groups in the church,” he said, noting that racism also played a role.

“For many Black young men, another reason why they never entered the priesthood was because they were never asked.”

Doherty said the filmmakers wanted to include men spanning a wide range of ages, from 20-somethings to retired priests.

Each one had an intensely personal reason for joining, he said, noting that he hopes to create a second film from unused footage focusing on these stories. He’s also interested in stories from women religious.

In the meantime, the young directors are receiving recognition for their first film. It has been featured on SiriusXM’s Catholic Channel and WFUV, and in June, it was named the 2024 recipient of Fordham’s William F. DiPietra Award in Film.

Rediscovering Faith

For Doherty, the project has enabled him to explore his own faith.

“When I came to Fordham, I think I really rediscovered the faith and what it means to be Catholic,” he said.

“I had many interactions with Jesuits, and they were all so brilliant and interesting,” he said.

“I found myself wondering, ‘How did they come to this life?’”

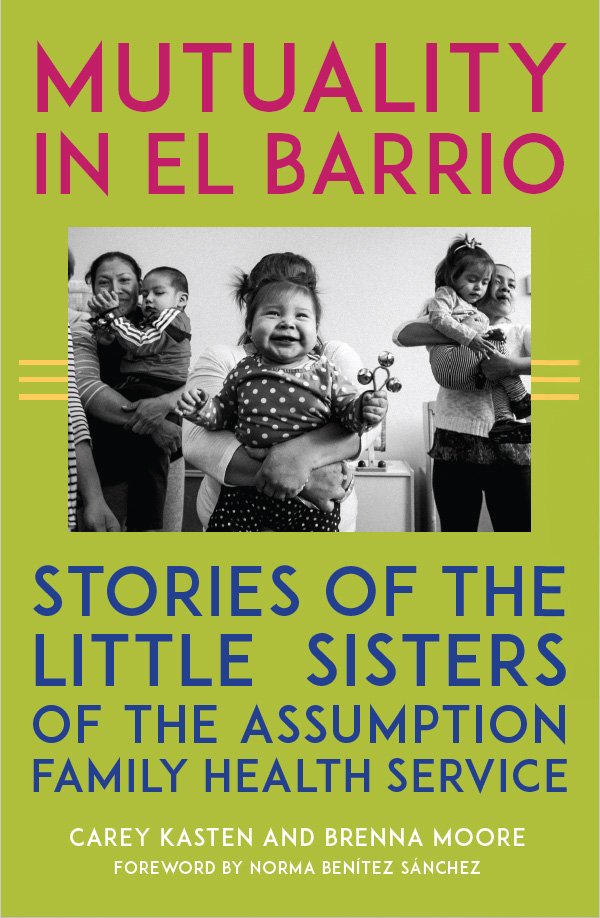

]]>Their focus is women and children who came to New York City from Mexico and found their way to the Little Sisters of the Assumption Family Health Service in East Harlem. There, they received holistic support that not only met their immediate needs but also empowered them to improve their circumstances, help others, and be leaders.

The agency “has been doing really effective work with diverse communities in a very complicated city and … developing power in a community that is typically disempowered,” said Fordham theology professor Brenna Moore, Ph.D. She and Carey Kasten, Ph.D., associate professor of Spanish at Fordham, are co-authors of Mutuality in El Barrio: Stories of the Little Sisters of the Assumption Family Health Service, out this month from Fordham University Press. A book launch takes place May 20.

Creating Pathways Out of Poverty

The Little Sisters of the Assumption, a Catholic order, founded its East Harlem agency in 1958 to create opportunities for families to escape poverty. The first executive director was Sister Margaret Leonard, GSS ’67, who codified the agency’s idea of mutuality.

It called for forming mutually enriching relationships with clients, “eschewing a binary framework of helper and helped in an effort to cocreate new realities in East Harlem that benefit all parties,” the book says.

That meant listening to migrants’ stories, offering mental and spiritual support, and unlocking their strengths over the long term. Sometimes it meant bringing them together so they could address common problems, like mold in their public housing. Former clients often return as volunteers and staffers or serve other New York City organizations in leadership roles.

What mutuality is not, Kasten said, is “looking for immediate effects.”

“It’s willing to be in conversation with someone for years and understanding that sometimes it does take that long,” she said. “The things that people are asked to do when they come to this country don’t take just a week.”

Success Stories of Migrants

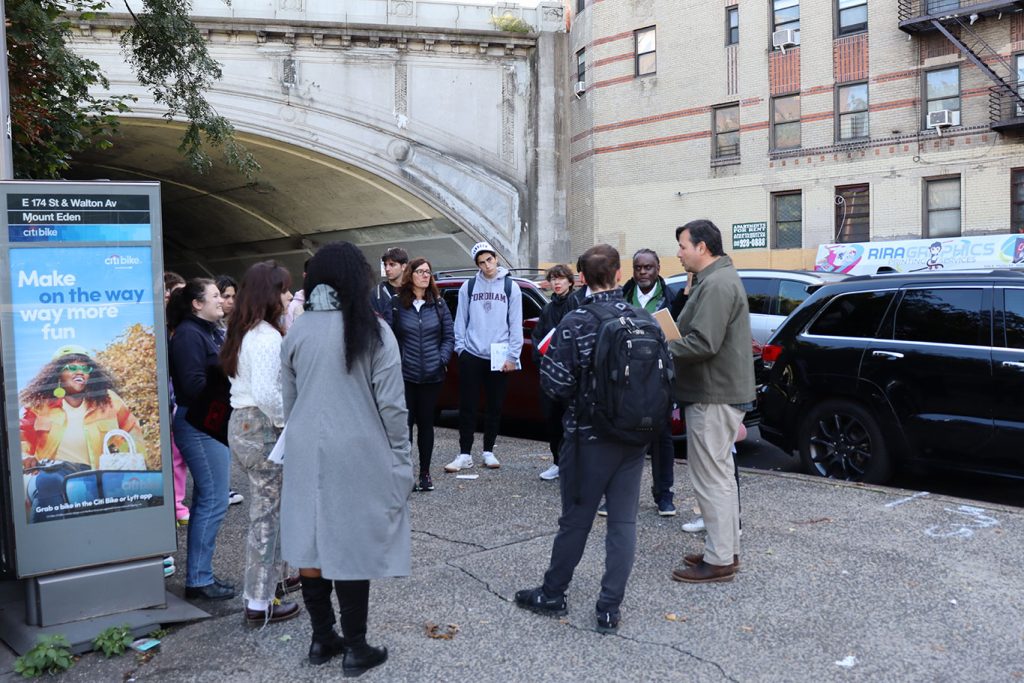

Eight Fordham students worked on the book project, gaining research experience by helping Moore and Kasten with interviewing migrants the agency served over the past few decades. The students included theology, Spanish, and communications majors, as well as students in the Graduate School of Social Service. Most migrants quoted in the book used pseudonyms.

The interviewees included Sonia, a onetime teenage mother whom the agency helped navigate prenatal care, develop parenting skills, and enroll in a pre-nursing degree program. The nuns also called upon her to provide nursing care to another Little Sisters client in her building.

And they stuck with her through crises—like being jailed on a false accusation from her child’s father, who had beaten her. The sisters prayed and sang hymns outside the jail overnight, giving her hope until charges were dropped the next day. She later moved to Florida, married, raised three children, and became head nurse in a hospital’s radiology department—at one point, overseeing the care of an ailing relative of Sister Margaret, who Sonia said is “like family.”

Another young mother, Yolanda, gained parenting skills through the agency and later joined its staff after earning her bachelor’s degree. “They began supporting me, motivating me,” she says in the book. In the words of another client: “They make you see what you don’t see in yourself.”

]]>Especially regarding the LGBTQ community, the Orthodox Church has consistently become “hung up on the division between Orthodox and un-Orthodox, the division between holy and unholy, taboo and sacred,” said Ashley Purpura, Ph.D., GSAS ’14, associate professor at Purdue University and visiting associate professor at Harvard Divinity School. “But there is a way that love is transcending [this divide].”

She spoke at “Seeking Harmony and Compassion: Helping Parishes with LGBTQ+ Ministry,” a discussion organized by Fordham’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center at the Lincoln Center campus. She was joined in conversation by Cristina Traina, Ph.D., Avery Cardinal Dulles Chair of Catholic Theology at Fordham.

“There is an urgency to the matter because [our churches] are turning people away who don’t feel they have a home,” said Traina.

Orthodox Christianity in the Modern World

Purpura noted that some portions of the Orthodox Church, notably the Moscow Patriarchate, have presented the LGBTQ community and pride parades as a part of a larger threat by the West to the church’s traditional values.

But others see a question of how the Orthodox Church lives out the Christian faith in the modern world. A growing number of clergy, laypeople, and academics—including Purpura—are offering a pastorally and theologically grounded response to ministering to LGBTQ Orthodox faithful.

Purpura studies how Orthodox Christian thought and practice in the Byzantine tradition haves shaped power structures, identities, and conceptions of gender. She was co-editor of Orthodox Tradition and Human Sexuality (Fordham University Press, 2022), which has a companion study guide.

Acceptance of the LGBTQ Faithful

During the talk, she touched on a number of ways that the Orthodox tradition can be a resource for acceptance of the LGBTQ faithful. For instance, gender binaries have been transgressed in the Orthodox tradition, she said, mentioning the case of Matrona of Perge, an Orthodox Christian female saint who lived for a time as a male monk.

Purpura also invoked the Orthodox tradition and, more broadly, Greek philosophy’s conceptions of love—including eros, or passionate love and desire, and agape, or selfless love for God and others.

In relationships filled with both, she said, “If we really see love—no matter what form it is taking—bearing fruit and already transfiguring that couple or those individuals, then I don’t understand how we can say that … this is not theotic,” transforming and advancing one’s relationship with God, or that “the presence of God [is not]in this union.”

She expanded this picture to include the entire church and all humanity, saying that divine-human communion “happens as a community” and in relationships. “It is not just an individual enterprise.”

‘Love Christ in Your Neighbor’

Thus, Purpura insisted that the Orthodox Church can no longer say the LGBTQ community does not intersect with the church’s past and present. Instead, all Christian communities are called to embrace all people through their capacity “to see Christ and love Christ in your neighbor.”

While maintaining the tradition as necessary and vital for the life of the Orthodox Church, Purpura emphasized that “what is most central, is our relationship with God, our experience of God’s love and communicating that love to others.”

“We cannot say we are loving God and then be cruel to the people who we encounter in our lives,” she said. “If you are not letting that love transform you and your relationships, then I do not know what Orthodoxy is.”

Orthodox Tradition and Human Sexuality resulted from a trailblazing project sponsored by the Oslo Coalition on Freedom of Religion or Belief that brought Orthodox clergy, academics, and laity together to engage in collective study and discussion.

— Harry Parks, Fordham College at Rose Hill, Class of 2024

]]>In the Ignatian Public Speaking workshop led by Robert Parmach, Ph.D., director of Ignatian mission and ministry, students learned about the finer points of “SPATE”—stance, projection, articulation, tone, and eye contact.

“We want to help graduate students develop skill sets that link to their Jesuit education,” said Parmach. In his introductory remarks, he invoked a lesson from St. Ignatius, founder of the Society of Jesus, reminding students that “developing the interior life … animates our spirit and connects us deeper to God and others.”

“Think about it,” he said. “The way you hold yourself in front of an audience demonstrates the kind of person you are and your character … The techniques we teach you provide ways to use your body and voice to motivate, lead, and transform others. It joins the mind, body, and soul to empower others and yourself along the way.”

In the workshop, the students practiced speaking in front of each other. Each was handed a written prompt, then given three minutes to digest it and a minute to summarize it for the group.

Lisa Cummings, a student at the Graduate School of Education currently teaching at the Orchard Collegiate Academy, said she felt “uplifted” by the workshop.

“I’ve been able to gather some useful tips, and it’s motivated me to try to create a workshop for my own students,” she said.

Asked to identify the one area of SPATE she felt she needed the most improvement, Cummings picked articulation. She recalled a mistake she made as an undergraduate at SUNY Morrisville.

“I had the opportunity to speak at my graduation, and I turned that opportunity down because of my fear of not being able to articulate myself well enough,” she said.

“That was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for me, and having passed up that opportunity, I really have made it a point to push myself to overcome that fear.”

Jay Vaghani, a Gabelli School of Business graduate student pursuing a master’s degree in quantitative finance, likewise found the workshop pushed him beyond his comfort zone. For his speech, he was given a prompt describing how the artist Sting reacted to a negative review of his music.

Vaghani, a native of Surat, Gujarat, India, who moved to the United States with the goal of transitioning from engineering to finance, has been hesitant to speak in public since he was a child.

He found it useful to focus on his tone and articulation. Although he was unfamiliar with Sting before reading the prompt, he said the short time he was given to prepare was paradoxically helpful because it forced him to focus on the content he’d be delivering and not the anxiety he felt.

“It was a great experience,” he said. “I look forward to doing another one.”

Fordham will receive the funds over three years, working with partner organizations to help uplift disadvantaged and hard-to-reach communities as well as those disproportionately affected by climate change, pollution, and other environmental stressors. Fordham is one of just 11 institutions nationwide selected to manage $550 million in federal funds earmarked for the program.

“Fordham University stands for impact on the world and finding solutions to the most urgent problems,” said President Tania Tetlow. “Fordham combines cutting-edge research with a deep connection to community, building on 182 years of engagement with the Bronx and expanding outward across the globe. This project embodies Fordham’s mission. We believe in the power of community-driven solutions to climate change to capture the insights and ingenuity of the people on the front lines of global warming.”

Approximately $10 million of the award will be designated for the grantmaking operation and related programming, as well as for Fordham’s own research. Serving as the EPA Region 2 grantmaker for the project, called the 2023 Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Grantmaking Program, Fordham will allocate the remaining $40 million in subgrants ranging from $75,000 to $350,000 to foster various environmental justice initiatives. Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning is leading the initiative, which will be directed by Julie Gafney, Ph.D., assistant vice president for strategic mission initiatives, and Surey Miranda, director of campus and community engagement.

Community and Academic Partners

The University is collaborating with key community and academic partners, including the New York Immigration Coalition, New Jersey Alliance for Immigrant Justice, ConPRmetidos in Puerto Rico, Community Foundation of the Virgin Islands, Business Initiative Corporation of New York, and several universities across the target regions. This collaborative approach will ensure a broader impact and integrate the University’s research and teaching with real-world environmental justice efforts.

Communities will be able to apply to Fordham for a subgrant to fund a range of different environmental project activities, including small local clean-ups, local emergency preparedness and disaster resiliency programs, environmental workforce development programs, air quality and asthma-related projects, healthy homes programs, and projects addressing illegal dumping.

The Fordham grantmaking initiative—called Flourishing in Community—will support each subgrant with a Community of Practice group that includes faculty, community leaders, and graduate assistants, ensuring comprehensive support and maximizing effectiveness.

“This grant is the direct product of Fordham’s commitment to center environmental justice and sustainability in our public impact teaching, learning, and research. In Fordham’s Flourishing in Community Grantmaker Initiative, we created a transformative approach that offers a new vision of higher education: one that values community impact alongside cutting-edge research,” said Gafney. “Our initiative not only provides grants to disadvantaged and disproportionately impacted communities but also extends to comprehensive wraparound support, ensuring the sustainability and impact of these crucial community-led projects.”

The grant also underlines Fordham’s commitment to STEM curricular development, as well as the University’s engagement with communities as they respond to the most pressing issues facing our city and our nation.

“We are grateful to have worked alongside our partners across EPA Region 2 to ensure accessibility to this much-needed funding for all,” said Miranda. “We aim to ensure that the most impacted communities can leverage the funding and technical assistance available through the program. This will help build their capacity and strengthen the work already taking place in New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.”

Lisa F. Garcia, EPA Region 2 administrator, said Fordham’s work with the agency “will be the start of a fruitful relationship that will build upon both EPA’s commitment to addressing climate injustice and Fordham’s promise of environmental stewardship.”

“As a grantmaker, Fordham University will help the EPA advance environmental justice in a direct way that will help to undo the past harms of environmental injustice,” Garcia said.

A ‘Transformative Opportunity’

Rafael Roger, president of Business Initiative Corporation of New York, one of Fordham’s partners, said the Flourishing in Community initiative is a chance to “begin addressing environmental issues that will improve the lives of millions of people.”

“This opportunity is transformative for our region and will bring justice to communities that have been marginalized,” he said. “While creating jobs and improving buildings is part of our mission, being able to add ‘improving the environment’ is a new benchmark.”

Amy Torres, executive director with the New Jersey Alliance for Immigrant Justice (NJAIJ), said that “too often, New Jersey is the punchline in jokes about pollution, contamination, or hazardous waste. But for New Jerseyans who bear the brunt of environmental racism or who have been displaced by climate crisis, it’s no laughing matter.”

“As the state’s largest immigration coalition, NJAIJ is proud to be a part of the collaborative effort under Flourishing in Community,” she said. “Together, we will uplift the voices of those most impacted in EPA Region 2—in particular climate refugees, agricultural workers, and people displaced or harmed by environmental racism.”

Dee Baecher-Brown, president of the Community Foundation of the Virgin Islands, said her organization is “honored” to be Fordham’s partner in this work.

“CFVI recognizes the significance and potential impact of this grant in advancing environmental justice and addressing the needs of overburdened communities, and is poised to employ our extensive experience and infrastructure to maximize the value of Flourishing in Community in the U.S. Virgin Islands,” Baecher-Brown said.

Also in the Caribbean, Isabel Rullán, co-founder and executive director of ConPRmetidos in Puerto Rico, said that she and her colleagues would bring their own grantmaking experience to bear and “prioritize supporting underrepresented groups focusing on eliminating barriers that limit organizational development.”

Murad Awawdeh, PCS ’19, executive director of the New York Immigration Coalition, said the organization is proud to partner with Fordham on its environmental justice efforts.

“This new funding from the EPA is an important first step in ensuring more community-based groups have the support they need to bring attention to and continue to alleviate the impacts of climate change, pollution, and other environmental stressors on immigrants, low-income communities, and people of color,” he said.

Those interested in learning more about the program—including how to apply for grants—can fill out this form.

For media inquiries, contact Jane Kidwell Martinez, Fordham’s director of media relations, at [email protected] or 347-992-1815.

]]>The document set forth an ambitious seven-year plan for the University that touches on everything from facilities and curriculum to student involvement, all with the ultimate goal of combating climate change.

Just this month, Fordham received a $50 million grant from the Environmental Protection Agency that the University will use to team up with community partners to address the issue.

Below are a few of the sustainability-related efforts, developments, and accomplishments that took place in the final quarter of 2023. Look for more updates in 2024!

Facilities

Going Hybrid

On Oct. 23, three hybrid minivans, including a wheelchair-accessible minivan, joined the fleet of Fordham’s Ram Vans. They replace gas-powered minivans previously used for wheelchair-accessible requests, trips to the Calder Center, and charter trip services. The vans use less gas, produce less CO₂, and can run up to 560 miles on one tank of gas.

Dining

Micro Farms

This fall, Aramark installed vertical hydroponic units called Babylon Micro Farms at dining halls on the Lincoln Center and Rose Hill campuses. They grow fresh greens and herbs in a water-based solution (instead of soil, which requires frequent watering.) The greens are harvested for use in dining hall dishes and special student events.

Compared to traditional methods, each micro farm uses 96% less water, zero pesticides, 65% less fertilizer, and zero miles to transport. As a result, between January and June 2023, using them allowed Fordham to save 19,247 gallons of water, prevent 2.5 pounds of nitrogen from entering waterways, and reduce 32 pounds of food waste.

Academics

In the Classroom

Six undergraduate community-engaged learning classes offered in the Fall 2023 semester featured elements promoting sustainability: Anthropology of Food (Anthropology), Economics and Ecology of Food Systems (Economics), Thinking Visually (Visual Arts), Human Physiology (Biology), Consumer Behavior (Gabelli School of Business), and Leadership Integrated Project (Gabelli School of Business). At Fordham Law School, environmental law courses offered this semester included Environmental Law and Energy Law.

Fordham Law students wrote blog posts for the school’s Environmental Law Review on the Flint and Jackson water crises, NYC Local Law 97, the environmental damage caused by the fashion industry, and cell-cultivated meats.

Reading Laudato Si’

The Curran Center for American Catholic Studies held three seminars on Zoom this semester dedicated to reading Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato Si’ and the 2023 follow-up, Laudate Deum. Visit the center’s website for more information on future seminars.

A Systems Approach

This semester, the Social Innovation Collaboratory and Career Center hosted a collaborative workshop on systems thinking, focused mainly on sustainability. The workshops, which were open to all undergraduate students, allowed them to explore the practice and application of systems thinking, which is rooted in a holistic approach to society’s more complex issues. The process is attractive to companies since it’s rooted in the idea of looking at complex problems with a new perspective. Contact Sadibou Sylla at the Collaborary for information on future workshops.

Students Take the Lead

Green Week: United Student Government sponsored Fordham College at Rose Hill’s Sustainability Week in November. It featured the Fordham Flea Pop-Up as well as a seminar on composting basics.

The Lincoln Center Environmental Club held a clean makeup tabling event on Nov. 30 to showcase the benefits of cruelty-free and clean makeup.

Community Engagement

As part of the Reimagine the Cross Bronx campaign, Fordham staff conducted weekend “walkshops” in the neighborhoods surrounding the highway. Funding came from a $25,000 grant from the New York City Department (DOT) that the Center for Community Engaged Learning received in October.

Fordham staff and students also held special Halloween and Thanksgiving-themed events at the Highbridge Farmers Market and community space, which was recently expanded thanks to an AARP grant.

Faculty News

Marc Conte, Ph.D., professor of economics, published “Unequal Climate Impacts on Global Values of Natural Capital” in the journal Nature.

Stephen Holler, Ph.D., associate professor of physics, published “Education for Environmental Justice: The Fordham Regional Environmental Sensor for Healthy Air,” in the journal Social Sciences.

David Gibson, director of the Center for Religion and Culture (CRC), received $84,840 from the Porticus Foundation for the annual conference The Way Forward: Laudato Si’, Protecting Our Common Home, Building Our Common Church. The conference will take place in February at the University of San Diego.

Isaie Dougnon, Ph.D., associate professor of French and Francophone Studies and International Humanitarian Affairs, received $24,790 from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for research based on a local perspective on water and migration in West Africa.

Alumni

Giselle Schmitz, GSAS ’22, spent this fall working with the Coral Triangle Center in Bali, Indonesia—a nonprofit that connects governments, corporations, and local groups to help strengthen marine resources in the region.

In Case You Missed It

It was a busy fall in terms of sustainability efforts! Here are some stories Fordham News covered that you may have missed: In October, the annual Fordham Women’s Summit focused on sustainability. In our theology department, a lecture for first-year students featuring Union Theological Seminary professor John J. Thatamanil connected religious supremacy to the destruction of the natural world. Four students have joined the Office of Facilities Management’s newly created internship program, while alumni are helping protect New York City’s birds and helping farmers adapt to climate change. The Gabelli School of Business hosted two Nobel Laureates at a conference on ESG. At the Law School, more than 20 students gathered in Central Park for a clean-up event for the annual Public Service Day, while alumna Melinda Baglio was honored for being a changemaker in the clean energy field.

Upcoming Events

Faculty Happy Hour: Sustainability and Environmental Justice

Open to all faculty interested in sharing ideas about sustainability.

Thursday, Jan. 18, 2024. RSVP: Julie Gafney, [email protected]

STEM Career Fair, Thursday, Feb. 15, Great Hall, Rose Hill Campus. Visit the Fordham Career Center next month for details.

Women of Color in STEM Career Panel, Wednesday, Feb. 28, Virtual. Visit the Fordham Career Center next month for details.

Social Impact and Non-Profit Micro-Fair, Thursday, March 14, 12th Floor Lounge, Lowenstein Center, Lincoln Center campus. Visit the Fordham Career Center next month for details.

Save the Date:

Climate Action Summit with President Tetlow: April 8, Rose Hill Campus

We’d Love to Hear From You!

Do you have a sustainability-related event, development, or news item you’d like to share? Contact Patrick Verel at [email protected].

]]>