Denzel Washington received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Joe Biden during a January 4 ceremony at the White House, where he was described as a generational talent and national role model.

“The admiration of audiences and peers is only exceeded by that of the countless young people he inspires,” the White House citation read. “With unmatched dignity, extraordinary talent, and unflinching faith in God and family, Denzel Washington is a defining character of the American story.”

Washington was one of 19 “truly extraordinary people” Biden recognized for “their sacred effort to shape the culture and the cause of America.” World Central Kitchen founder José Andrés, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and primatologist Jane Goodall were among the other honorees.

The award was a year and a half in the making for Washington, whose many honors include two Academy Awards, a Tony Award, two Golden Globes, and the Cecil B. DeMille Lifetime Achievement Award. He had been slated to receive the medal from Biden in July 2022, but a case of COVID-19 kept him from attending the ceremony that year.

This year’s honor comes on the heels of his starring role in the film Gladiator II, and as he prepares to return to Broadway to star alongside Jake Gyllenhaal in a revival of Shakespeare’s Othello. Performances are scheduled to begin on February 24 at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre.

Washington last played Shakespeare’s “noble Moor” five decades ago, as a Fordham senior. He starred in a March 1977 production of the play at the University’s Lincoln Center campus, about a dozen blocks north of where he’ll reprise the role next month.

Fordham Roots—and a Legacy of Giving Back

Washington grew up in Mount Vernon, New York, not far from Fordham’s Rose Hill campus. He has often said that he “kind of backed into” acting—and fell in love with it—during his time at the University.

One of the first people on campus to recognize Washington’s potential was English professor Robert Stone. Decades earlier, he had acted with the legendary Paul Robeson in a Broadway production of Othello.

“Denzel gave the best performance of Othello I’d ever seen,” Stone told Fordham Magazine in 1990, referring to the 1977 Fordham production. “He has something which even Robeson didn’t have … not only beauty but love, hatred, majesty, violence.”

Since his college days, Washington has become a Hollywood and Broadway legend, deeply respected not only as an actor but also as a producer and director.

No matter how many accolades he amasses, however, he makes time to give back: For more than 25 years, he’s served as national spokesman for the Boys & Girls Clubs of America. And he gives to the Fordham community. In 2011, he made a $2 million gift to endow the Denzel Washington Chair in Theatre and a $250,000 gift to establish the Denzel Washington Endowed Scholarship for an undergraduate student studying theatre at Fordham.

Through the chair, scholarship, and campus visits, Washington has been a mentor to young Fordham artists.

Eric Lawrence Taylor, FCLC ’18, a former recipient of the Denzel Washington Endowed Scholarship, described the actor’s subtle mentoring style best in a 2018 interview: “In a very cool, non-publicity-seeking way, Denzel Washington has been mentoring artists of color for a long time,” he said, “and really providing space for a lot of us to succeed.”

VIDEO: Watch Denzel Washington Receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom

Fordham’s 6 Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients

The Presidential Medal of Freedom—the nation’s highest civilian honor—is presented to individuals who have made exemplary contributions to the prosperity, values, or security of the United States, to world peace, or to other significant societal, public, or private endeavors.

Washington is now the sixth Fordham graduate to receive the medal since 1963, when it was established by President John F. Kennedy. Here are Fordham’s other honorees:

Cardinal Terence Cooke: A New York City native, Cooke was ordained a Catholic priest in 1945 by Fordham graduate Cardinal Francis Spellman, archbishop of New York. He taught at the University’s Graduate School of Social Service during the 1950s and earned a master’s degree from Fordham in 1957. After Cardinal Spellman’s death in 1968, Cooke was named archbishop of New York and, later, military vicar to the U.S. armed forces.

President Ronald Reagan honored him posthumously in April 1984, six months after Cardinal Cooke died of leukemia at age 62, calling him a “man of compassion, courage, and personal holiness.”

Sister M. Isolina Ferré: Born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in 1914, the youngest daughter of one of the island’s wealthiest families, Ferré entered the Missionary Servants of the Holy Trinity in 1935. In the 1950s, her work as a nun brought her to New York. She earned a master’s degree in sociology from Fordham in 1961 while gaining national recognition for her work with Puerto Rican youth gangs in Brooklyn. She later established community aid centers in Ponce, and in 1988 founded Trinity College of Puerto Rico, a school that provides leadership and vocational training.

President Bill Clinton honored her in August 1999, praising her ability to combine “her deep religious faith with her compassionate and creative advocacy for the disadvantaged.”

Irving R. Kaufman: A 1931 Fordham Law School graduate, Kaufman is perhaps best known as the federal judge who sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to death on April 5, 1951. But he also ruled in some landmark First Amendment, antitrust, and civil rights cases during four decades on the bench.

When he died in 1992 at age 81, The New York Times wrote, “It was Judge Kaufman’s hope that he would be remembered for his role not in the Rosenberg case, the espionage trial of the century, but as the judge whose order was the first to desegregate a public school in the North, who was instrumental in streamlining court procedures, who rendered innovative decisions in antitrust law and, most of all, whose rulings expanded the freedom of the press.”

President Ronald Reagan honored Kaufman in 1987 for his “exemplary service to our country” and “his multifaceted effort to promote an understanding of the law and our legal tradition.”

Jack Keane: A retired four-star U.S. Army general and widely respected national security and foreign policy expert, Keane grew up in a housing project on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He began his military career at Fordham as a cadet in the University’s Army ROTC program. After graduating in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in accounting, he served as a platoon leader and company commander during the Vietnam War, where he was decorated for valor. A career paratrooper, he rose to command the 101st Airborne Division and the 18th Airborne Corps before he was named vice chief of staff of the Army in 1999. Since retiring in 2003, he has often provided expert testimony to Congress. He received the Fordham Founder’s Award in 2004, and he is a Fordham trustee fellow.

President Donald Trump honored Keane in 2020, lauding him as “a visionary, a brilliant strategist, and an American hero.”

Vin Scully: A 1949 Fordham graduate, Scully is best known for his nearly seven-decade stint as voice of the Dodgers—first in Brooklyn, later in Los Angeles—and widely considered one of the best sports broadcasters of all time. He got his start at WFUV, Fordham’s public media station, announcing football, basketball, and baseball games before joining the Dodgers broadcast team in 1950. Scully was inducted into the broadcasters’ wing of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, and Fordham presented him with an honorary degree in 2000.

President Barack Obama honored Scully in 2016. “Vin taught us the game and introduced us to its players. He narrated the improbable years, the impossible heroics, [and] turned contests into conversations,” Obama said.

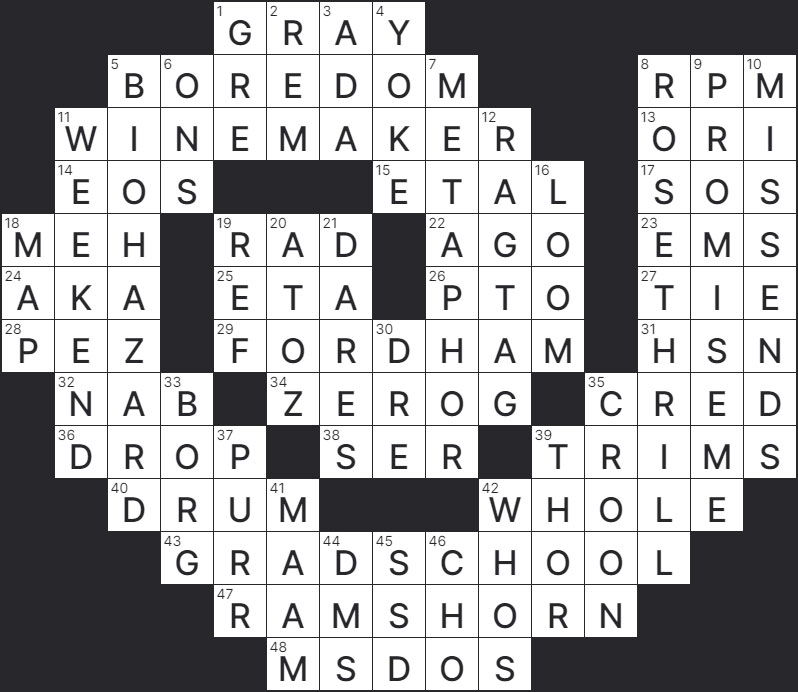

I sat beside my parents on the crowded gym floor, impressed by what the president, Joseph A. O’Hare, S.J., said about students who make the city their classroom. And I thought about basketball, too. As a Knicks fan, I knew that broadcaster John Andariese was a Fordham grad. I’d learn much later that his Fordham coach was Johnny Bach, the master of the “Doberman defense” who helped lead Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls to three straight NBA titles in the early 1990s.

As the Rose Hill Gym turns 100 this season, it’s hard to imagine a better exemplar of its spirit than Bach, a Fordham grad of grit and class.

Bach was a decorated World War II veteran who bookended his Navy service with studies at Fordham. He enrolled in 1942, returned in 1947, and graduated the following year with a degree in economics. That final year, he starred on the men’s basketball team, earning team MVP honors.

He also encountered a 34-year-old Vince Lombardi, FCRH ’37, in the gym. The Fordham grad and future NFL legend was coaching the freshman basketball team at the time. At the start of the season, he instructed his players to stand along the baseline, Bach recalled. “Fordham University and God have ordained me to coach you,” Lombardi told them, “and I want every one of you who is willing to be coached … to step across that line.” It was the kind of affirmation that Bach carried with him throughout his life, Bulls head coach Phil Jackson once said—an affirmation about being coached and being part of a team.

After graduating from Fordham in 1948, Bach played for the Boston Celtics before returning to Rose Hill in 1950 as head coach. It wasn’t a career change he took lightly.

“I think everyone who goes into coaching must have some apprehension,” he once told a reporter, “because it’s far more than basketball. It’s philosophy and discipline. It has so many demands.”

For 18 seasons, he coached the basketball Rams to more wins than anyone else in Fordham history. And he remained an enthusiastic coach and educator for 56 years, the final 25 in the NBA. He had a gift for making the game “come alive in terms that [everyone] fully understands,” to quote a 1993 Fordham Magazine profile of him.

A Proud Product of a Fordham Jesuit Education

After Bach died in 2016, Mary Sweeney Bach told a reporter that her late husband’s Fordham education was key to his success as a coach.

“He was very proud of being the product of a Jesuit education because he believed in the importance of … being spiritually honest, intellectually honest. He believed in the importance of education. That’s part of what made him the kind of coach he was,” she said. “It wasn’t just rah rah, go get ’em. He was so much into teaching the basics, the fundamentals, the values; it was the basics of life as well as the basics of basketball.”

She also said that her husband admired how Michael Jordan “elevated the people around him” on the court. Likewise, Bach left an indelible mark on countless athletes, including Jordan, who described him as a mentor, friend, and “truly one of the greatest basketball minds of all time.”

What connects Bach not only to our story about the gym but also to the profiles of alumni changemakers and to Fordham’s “Best for Vets” reputation is his passion for teamwork and for building up those around him.

“When you love what you do,” he once told this magazine, “it really isn’t a job.”

]]>B.A. Van Sise was driving his young nephew to the Cherokee Heritage Center in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, several years ago when he heard Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson on the radio. The Moana actor was reflecting on his Samoan heritage. For years he had a hole in his heart, he said, because he didn’t speak the language of his maternal ancestors.

“I suddenly had this moment of epiphany,” Van Sise recalled.

Since graduating from Fordham College at Lincoln Center in 2005, Van Sise has worked as a photojournalist, artist, and author, but he studied linguistics at the University, and his degree is in both visual arts and modern languages. He took courses in Italian and Russian, and he also speaks French, German, and Ladino, an endangered language he learned from his mother and maternal grandfather growing up in New York.

“I realized I wanted to explore language in America,” he said. “What does American language look like?”

It’s more diverse than you might think.

The Resilience of America’s Endangered Languages

English has been dominant on the North American continent for centuries, subsuming other languages, “turning them upside down and shaking their pockets for loose vocabulary,” Van Sise said. And yet, “against unspeakable odds”—despite colonial forces, disease, cultural displacement, migration, and remixing—hundreds of Indigenous and diasporic languages exist in America.

Much of these languages’ variety and complexity is on brilliant display in Van Sise’s latest book, On the National Language: The Poetry of America’s Endangered Tongues, and in a solo exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles through March 2.

The book features speakers, learners, and revitalizers of more than 70 languages in the United States. From Afro-Seminole Creole to Zuni, each language featured includes a brief cultural summary. And each portrait is paired with a single, often hard-to-translate word designed to inspire Van Sise’s visual approach and “show off the poetry inherent in each language,” he said. “Fundamentally, it is not an ethnicity project. It’s about the poetry of languages.”

In that sense, it’s a sequel of sorts to Van Sise’s first book, Children of Grass: A Portrait of American Poetry (2019), and it bears a kinship to his portraits and essays about Holocaust survivors in Invited to Life: Finding Hope After the Holocaust (2023). Like Holocaust survivors he met, endangered language speakers and revitalizers are “obsessed with the future,” Van Sise said, “the future of their stories, their legacies, their own families, and the people who come after them.”

Van Sise initially thought he might photograph “the last speakers” of various languages, “a really colonialist idea that I’m slightly embarrassed of,” he said. But he ultimately focused on the many people and groups working to revitalize—and in some cases resurrect—these languages. He traveled to 48 states with pivotal support from the Philip and Edith Leonian Trust, he said, and worked with dozens of Indigenous and diasporic cultural organizations, Native tribes and nations, and the Tribal Trust Foundation.

And while he photographed a Bukhari speaker and a Judeo-Spanish singer in his hometown of New York City, most locations weren’t so easy to reach. “Endangered languages really do best in places that are remote and where communities can still speak to each other,” he said.

Striving for Balance

Laura Tohe, former poet laureate of the Navajo Nation, met Van Sise near the Superstition Mountains, two hours east of Phoenix. She had a turquoise dress made specifically for the photo session, and “God gave me the sky” to match, Van Sise said. His playful sense of humor is on display in the way he and Tohe depicted hózhó, or striving for balance, “an extremely famous concept in Diné,” the Navajo language, he said.

Whimsy is also evident in Van Sise’s portrait of former Houma chief Kirby Verret in Gibson, Louisiana. Verret and an alligator teamed up to show off the Houma French word onirique, or something that comes from a dream.

Van Sise spent nearly a week with Amish community member Sylvan Esh before Esh agreed to work with Van Sise on the photograph. Part of getting to know Esh included waking up at 4 a.m. several days in a row to milk his cows, Van Sise said. The Pennsylvania Dutch concept he ultimately depicted with Esh, dæafe, or to have permission to do something, is “extremely, unbelievably important in the culture,” Van Sise said.

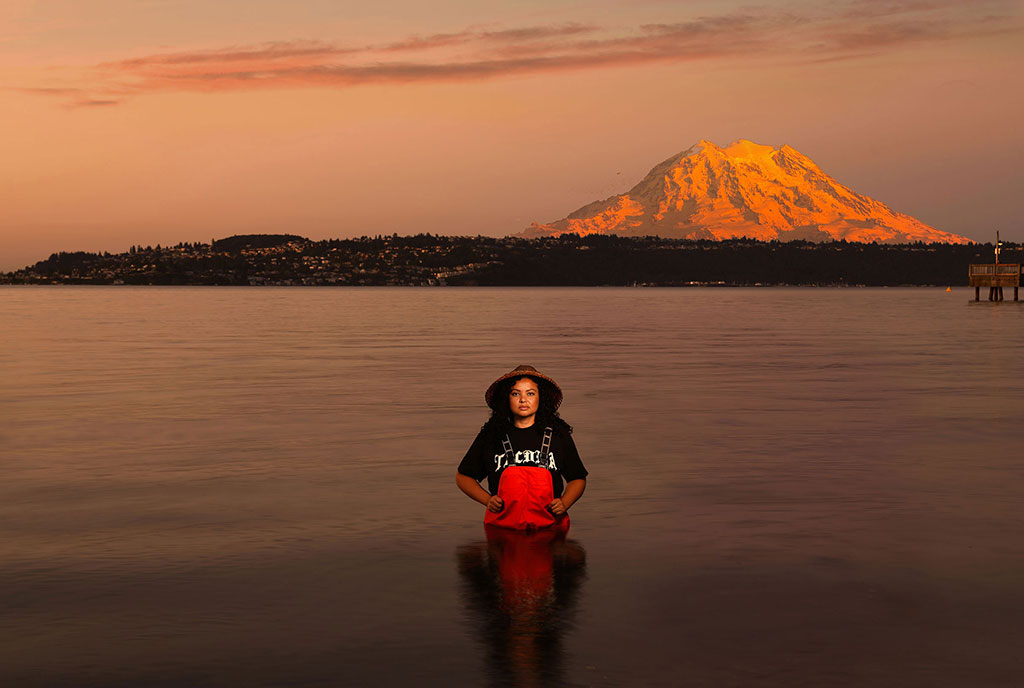

A Movement to Revive Lost Languages

Amber Hayward, a member of the Puyallup tribe in Tacoma, Washington, chose the Lushootseed word ʔux̌ʷəlč, or the sound of saltwater waves washing onto the beach. Lushootseed once numbered 12,000 speakers along the Puget Sound “before going extinct approximately twenty years ago,” Van Sise writes. As director of the Puyallup language program, Hayward has aided its rebirth. It’s just one of several languages featured in the book that boast healthy revitalization programs.

Another is the Kalispel language, represented by Jessie Isadore. She recommended the word cn̓paʔqcín, or the dawn comes toward me, said Van Sise, who explained that Kalispel is one of several languages historically spoken in what is now Montana and Washington state that make no distinction between nouns and verbs. “The whole thing just becomes one idea,” he said. “There’s something really lovely about that.”

Nahuatl is one of few languages highlighted in the book that is not spoken primarily in the U.S., but Van Sise could not resist the Aztec language’s centuries-old tradition of making as big a poem as possible with a single compound word. He and Los Angeles–based folkloric dancer Citlali Arvizu (pictured at the top of the story) chose tixochicitlalcuecuepocatimani, or, you are bursting into bloom all over with stars like flowers.

Working with people like Arvizu to create “visual poems” in these languages is more than an artful way to document linguistic diversity. For Van Sise, the goal is to raise awareness and inspire further education and preservation.

“I can’t do much to make the Haida language revitalization program more robust,” he said, picking just one example. “But I can provide the sizzle for the steak.”

8 Uncommon Words to Spark Your Interest in Endangered Languages

B.A. Van Sise’s book On the National Language features conceptual portraits of more than 70 speakers, learners, and revitalizers of endangered languages in the U.S. Each image is inspired by a single word in the speaker’s language, one that isn’t always so easy to translate into English. He hopes readers might “find one impossible word, and want to learn another and another.” Here are eight.

tekariho:ken

between two worlds

Mohawk

kapará

worse things have happened

Judeo-Spanish, or Ladino

puppyshow

showing off behavior

Afro-Seminole Creole

amonati

something you hold and keep safe for others

Bukhari

koyaanisqatsi

nature out of balance

Hopi

ma’goddai

feeling when the blood rises that makes you act both violently and lovingly

Chamorro

opyêninetêhi

my heart is taking its time

Sauk

uŋkupelo

we are coming home

Lakota

Why add another book to those bulging shelves?

Because the six-month lead-up to D-Day illuminates Eisenhower’s singular diplomatic skills, Paradis writes in The Light of Battle, and his “underappreciated role in America’s rise as a superpower.”

Paradis—a human rights lawyer, historian, and fellow at the Center on National Security at Fordham Law School—does this by focusing on the six months leading up to the invasion, starting with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s decision to select Eisenhower over General George C. Marshall as supreme allied commander.

Paradis draws on deep archival research and newly found letters to build a compelling portrait of Eisenhower’s character and capabilities. The future U.S. president’s “most fateful choices” were diplomatic, Paradis writes, as he tactfully navigated the political and logistical difficulties of planning such a high-risk, high-reward operation. He managed to double the size of the planned invasion and persuade Winston Churchill and the British, among other international leaders, to go along with the plan.

In vivid, humanizing detail, Paradis brings out the roiling drama centered around Eisenhower, who often had to project optimism even when he knew the venture was on the verge of collapse.

“By avoiding the grandiosity associated with great power,” Paradis writes, and beaming American openness and opportunity, “Eisenhower made it easy to believe that there was nothing to fear. He wore his ambition lightly … [in]service to a cause greater than himself.”

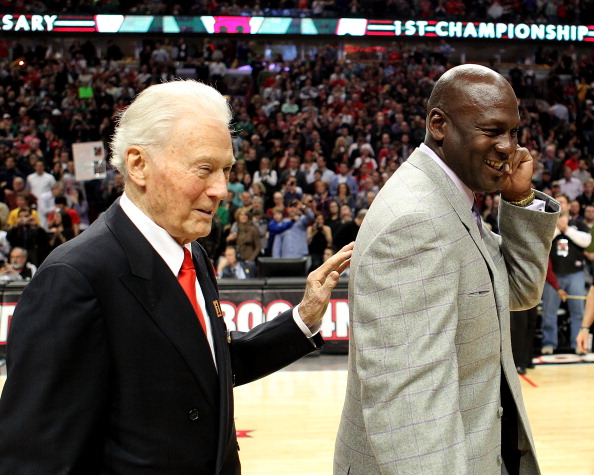

]]>Spoiler Alert: The solution to the fall/winter puzzle is posted below. If you’d like to receive a copy of the print edition, write to us at [email protected].

How did you get interested in creating crossword puzzles, and how long did it take before you published your first one?

Growing up, I solved Sunday New York Times puzzles with my dad. Soon after my studies at Fordham, I found myself wondering what it took to make crosswords and started looking into it. I officially started constructing crosswords in November 2016. I was unemployed at the time and in desperate need of a distraction from world events.

Incredibly, I went from purchasing crossword construction software to getting my first puzzle accepted—a Sunday New York Times puzzle, no less—in just six weeks. I was guided by an incredible mentor, Nancy Salomon, and spurred on by an insatiable hyperfixation with the task of creating a satisfying, interesting, unique crossword. Since then, I’ve immersed myself in the crossword community, learned from so many people, and in 2022 began editing puzzles for two publications—AVCX and Puzzmo. It’s incredibly enriching work.

What do you think makes a crossword puzzle satisfying for people to solve? And what do you hope solvers feel when they complete one of your puzzles?

As a solver, I enjoy accessible, whimsical puzzles that balance wordplay, trivia, and pop culture references, so those are the kinds of crosswords I like to make. Crosswords are an art form, a means of expressing oneself. Each puzzle I make has personal touches and feels special to me. I hope that solvers learn a little something from my puzzles, have some nice “ah ha” moments, and finish with a smile on their face.

Do you have a favorite puzzle you created or some favorite clues you came up with?

I have a few standout favorites among the hundreds of puzzles I’ve made. One that comes to mind is a Sunday New York Times crossword called “All Aflutter,” in which I used grid art and the placement of a single extra letter in the grid to demonstrate the philosophical concept of the butterfly effect for the solver. I remember that when this idea struck me, it consumed a whole day—I sat in bed, obsessively designing the grid for hours and hours as it came together. I knew I was onto something special.

What’s your favorite clue and answer in the puzzle you created for the fall/winter issue of the Fordham mag?

I love the wordplay clue for WINEMAKER: “One working with vintage materials?” It’s always fun to come up with a fresh new misdirect, and I thought that was a clever one. I also enjoyed being able to be self-referential with the FORDHAM clue, putting myself in the same category as some major celebs! How fun is that?

Do you ever receive feedback on your puzzles, and is there a reaction or anecdote that sticks with you?

In April 2024, I attended the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament in Stamford, Connecticut, for the first time. We all had lanyards with our names on them, and I was totally starstruck by some major figures in the crossword community that I got to meet. It was surreal, then, to have a few people come up to me and tell me that they love my puzzles. Certainly that’s the closest I’ll ever be to experiencing fame!

You earned a master’s degree in mental health counseling from Fordham’s Graduate School of Education in 2015. Why Fordham, and what was the grad-school experience like for you?

After graduating from Vassar in 2013, I decided I wanted to work in higher education, and that a counseling degree was the way to go. The Fordham program appealed to me because of its focus on multicultural approaches to counseling, and I loved the idea of going to school in the center of Manhattan. I greatly enjoyed my classes at Fordham; the teachers were extremely knowledgeable, and I found the curriculum to be well-designed.

Crosswords can be mentally stimulating, even a kind of meditative experience for people. How do you view them when it comes to education and mental health? Is there a connection to your graduate studies at Fordham?

One thing I love about solving crosswords is that there are countless ways to get to the right answer. People come to the table with different knowledge and lived experience, which means that the way I solve a crossword will differ from how you might solve it. The experience is really an exercise in exploration, of uncovering the grid, piece by piece, until it all comes together in the end.

I see a connection here with mental health. Therapy is a tool we use to explore our beliefs, relationships, and traumas, unknotting the messy knots that we get caught up in. After an especially effective therapy session, I feel a sense of satisfaction, relief, and gained knowledge about myself and the world. It is an exercise in exploration, in discovery. I have experienced similar feelings after solving a crossword.

Anything you’d like to add that I didn’t bring up?

If you’re interested in following more about me and my crossword work, or want to reach out with a question or comment, please feel free to find me on Bluesky, under the username Livienna. You can also find my daily categories game, Overlapt, over at the Puzzle Society!

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Ryan Stellabotte.

Solution to the Puzzle in the Fall/Winter 2024 Print Edition of Fordham Magazine

]]>Less than 24 hours after “a wildfire ripped through postcard-perfect Lahaina on the Hawaiian island of Maui,” Vigliotti and his Los Angeles-based national news team were on a deep-sea fishing boat “carving a coast-hugging path through the swelling Pacific.” It was the only way to bypass police roadblocks that residents told him were “less about protecting people from danger than preventing journalists from documenting a crippled emergency response and growing humanitarian crisis.”

Vigliotti got his start as an undergraduate at WFUV, Fordham’s public media station. Since graduating in 2005, he has reported on “historic hurricanes, thermometer-shattering heat waves, record-breaking droughts, megawildfires, back-to-back ‘hundred-year floods,’ unprecedented blizzards, and never-before-seen mudslides,” he writes.

In the book’s four sections—fire, water, air, and Earth—he examines the conditions of each of these catastrophic events and the consequences of government inaction. He blends the harrowing stories of “everyday Americans” struggling to survive in “a habitat threatening to erase their ways of life” with scientific context and glimmers of hope from conservationists.

The result is a persuasive call to make the changes needed to save our home before it’s too late.

]]>Take Frances Berko, for example. A pioneer in the disability rights movement, she earned a Fordham Law degree in 1944. By 1949, Berko, who had ataxic cerebral palsy, helped start United Cerebral Palsy. She later served as New York state’s advocate for the disabled.

“I’ve had much success,” she told a panel of legislators in 1981. “But the one achievement which I held most precious—for which I’ve most constantly striven—I’ve never been able to attain completely: that is, the full rights of a citizen of this country and this state.”

That achievement came in 1990 with the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act. In 1994, two years before Berko died, Fordham awarded her an honorary doctorate, and Janet Reno, then U.S. attorney general, called her “a symbol to me of what you can do and how you can do it magnificently.”

Today at Fordham, Berko’s spirit is evident in the work of senior Abigail Dziura, who has focused her research on improving the New York City subway system, where only 27% of all stations are considered fully accessible to people with disabilities.

In April, she earned a prestigious Harry S. Truman Scholarship, which recognizes college students dedicated to public service. “One of the hardest parts of advocacy work is knowing that you don’t always get to see the end result,” she told Fordham News. “Sometimes you’re setting things up for future generations because something can’t be completed for another 20 years. … But someday, I’d love to see a fully accessible New York subway system.”

The ever-striving, regenerative spirit that links Berko to Dziura and beyond is just one example of Fordham people working to build stronger communities. You’ll find more in our latest “20 in Their 20s” series.

]]>Disorderly Men: A Novel

In Disorderly Men, Fordham English professor Edward Cahill evokes New York City in the mid-20th century, several years before the 1969 Stonewall uprising catalyzed the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. The novel opens with a police raid on Caesar’s, a mob-owned gay bar in Greenwich Village, where Roger Moorehouse, a Wall Street banker and World War II veteran with a wife and children in Westchester, was about to leave with “the best-looking boy” in the place. “Fragments of his very good life—the fancy new office overlooking lower Broadway, the house in Beechmont Woods, Corrine and the children—all presented themselves to his imagination as fitting sacrifices to the selfish pursuit of pleasure,” Cahill writes.

In Disorderly Men, Fordham English professor Edward Cahill evokes New York City in the mid-20th century, several years before the 1969 Stonewall uprising catalyzed the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. The novel opens with a police raid on Caesar’s, a mob-owned gay bar in Greenwich Village, where Roger Moorehouse, a Wall Street banker and World War II veteran with a wife and children in Westchester, was about to leave with “the best-looking boy” in the place. “Fragments of his very good life—the fancy new office overlooking lower Broadway, the house in Beechmont Woods, Corrine and the children—all presented themselves to his imagination as fitting sacrifices to the selfish pursuit of pleasure,” Cahill writes.

Also caught up in the raid are Columbia University professor Julian Prince and his boyfriend, Gus, a “serious-minded painter” from Wisconsin who gets knocked unconscious by a police baton; and Danny Duffy, a Bronx kid who helps manage the produce department at Sloan’s Supermarket. They’re charged with “disorderly behavior,” and their lives are upended—Roger is threatened by a blackmailer, Danny loses his job and family and seeks revenge, and Julian searches for Gus, who goes missing.

Cahill depicts their crises with pathos, humor, and suspense. And like the best historical fiction, Disorderly Men not only evokes a bygone era but also feels especially vital today.

Midnight Rambles: H. P. Lovecraft in Gotham

The cult writer H. P. Lovecraft was not well known during his lifetime, most of which he spent in his native Providence, Rhode Island. But the so-called weird fiction he wrote in the 1920s and 1930s—a blend of horror, science fiction, and myth—has “entranced readers” and influenced artists in various media ever since, David J. Goodwin writes in Midnight Rambles.

The cult writer H. P. Lovecraft was not well known during his lifetime, most of which he spent in his native Providence, Rhode Island. But the so-called weird fiction he wrote in the 1920s and 1930s—a blend of horror, science fiction, and myth—has “entranced readers” and influenced artists in various media ever since, David J. Goodwin writes in Midnight Rambles.

From shows like Netflix’s Stranger Things to the films of Academy Award-winning director Guillermo del Toro to the novels of Stephen King and beyond, artists have been inspired by Lovecraft’s “vivid world-building and bleak cosmogony.” They’ve also been repulsed by his racist and xenophobic views.

Goodwin, the assistant director of Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture, deals with this head-on in Midnight Rambles, a chronicle of the writer’s love-hate relationship with New York and the city’s effect on him and his writing. He describes the brief period—from 1924 to 1926—when Lovecraft lived in Brooklyn, drawn there by Sonia Greene, a Ukrainian Jewish émigré he met at a literary convention in Boston. Their marriage soon fell apart, and he moved back to Providence, where he died in 1937 at age 46. “An extended encounter with a great city reveals and exaggerates the strengths, foibles, attributes, and flaws of a character in a film or a person in the flesh-and-blood world,” Goodwin writes. “This is certainly true of Lovecraft and his years in New York City.”

]]>“Carol Robles was a dynamo her entire life,” U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor said in a statement. “She devoted herself to public service and made a noteworthy difference both in the lives of Latinos and all New Yorkers. Her passing is a tragedy for her family and all of us.”

A 1983 graduate of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, Robles-Román served as deputy mayor for legal affairs during Michael R. Bloomberg’s three-term tenure as mayor, from 2002 through 2013. She was the highest-ranking Latina in city government at that time and the first woman ever to serve as counsel to a New York City mayor.

From City Hall, she oversaw more than a dozen agencies. Her accomplishments include launching the city’s Family Justice Centers to provide free, confidential, and comprehensive assistance to survivors of domestic violence. She also expanded the city’s language-translation services to better meet the needs of non-native English speakers. And she was instrumental in creating the Latin Media and Entertainment Commission to help “bring the best in Latin media and entertainment productions, businesses, and jobs” to the city.

After serving in the Bloomberg administration, she led two national civil rights organizations: Legal Momentum—the Women’s Legal Defense and Education Fund, and the Equal Rights Amendment Coalition/Fund for Women’s Equality. In recent years, she had been general counsel and dean of faculty at Hunter College. She also was a longtime member of the City University of New York Board of Trustees.

“Carol Robles-Román dedicated her life to public service and to making our city and country more equal and just,” Bloomberg wrote in a statement, citing her “groundbreaking work to make the city more accessible to our … immigrant and disabled communities, and to stop domestic violence and human trafficking.”

In a 2015 profile in Fordham Magazine, Robles-Román described her approach to identifying societal problems and mobilizing both the political will and the means to fix them.

“Part of my ethos is being a disruptor—in a nice, good way,” she said. “It’s about creating strategic partnerships to make change happen.”

‘Women Can Have a Powerful Voice’

Robles-Román was born in East New York, Brooklyn, on August 27, 1962. Her parents, Emilio and Inéz Robles, owned an insurance brokerage and travel agency, and they were engaged with multiple local civic groups focused on voter registration, housing, and health care, among other issues. They had migrated to New York City from their native Puerto Rico in the mid-1950s, and in the early 1970s, they moved the family to Howard Beach, Queens.

“My mother raised six children—five girls—so it was particularly important to her to teach us, as women of color, that women can have a voice and can have a powerful voice,” Robles-Román once said. “Many women never learn that. That’s the gift she gave me.”

A Puerto Rican Power Couple

After graduating from Stella Maris High School in 1979, Robles-Román enrolled at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where she majored in political science and media studies.

“I felt very, very comfortable speaking in my own voice and being assertive, and in pursuing my joint passions: civics issues and writing,” she told Fordham Magazine in 2002.

In an international law class, she introduced herself to Nelson Román, FCRH ’84, a fellow student of Puerto Rican descent who would become her husband in 1991. Román, who is now a federal judge in the Southern District of New York, worked as a police officer in the Bronx while he was enrolled at Fordham. He told her what he witnessed while responding to domestic violence calls, and the stories he shared left her bothered but determined to help. She researched best practices for handling such incidents and published her work in a Fordham pre-law journal.

“Ever since then, domestic violence and the treatment of women has been an issue that she’s held very close to her soul,” Román told Fordham Magazine in 2015.

A Champion of Sonia Sotomayor

After graduating from Fordham, Robles-Román worked as a paralegal and eventually earned a J.D. from New York University. In the mid-1990s, she met Sonia Sotomayor, then a federal district court judge, through the Puerto Rican Bar Association. Like many young lawyers in the bar association at the time, she came to regard Sotomayor as a mentor.

“She’s a very warm woman, she’s a very nurturing woman, and she also shared her substantive legal intellect with us very early on,” Robles-Román told CNN in 2013.

In the late 1990s, when Nelson Román was president of the Puerto Rican Bar Association, he and Robles-Román helped lead a grassroots campaign to get a Latino justice on the Supreme Court. Sotomayor was on their short list.

A decade later, in May 2009, when President Barack Obama nominated Sotomayor to serve on the nation’s highest court, Robles-Román helped prepare Bloomberg to speak at a congressional hearing in support of her nomination. Three months later, she became the first Latina Supreme Court justice in U.S. history.

“I felt like this is the message Judge Román and I had been sending our whole lives,” Robles-Román said in 2010. “We have excellent Hispanic judges and attorneys, and it feels like it’s been our job to shine a light on that.”

Prior to joining the Bloomberg administration, Robles-Román served as a senior attorney to a family court judge and as special counsel and eventually director of public affairs for the New York State Unified Court System, where she focused on bias matters, among other issues. She also served as a New York state assistant attorney general in the state’s civil rights bureau.

A Mentor to Young People

During her tenure as deputy mayor of New York City, Robles-Román created what she called her Girl Power School talk, which she presented primarily to middle and high schoolers. She encouraged them to focus on the steps—like writing a resume, finding mentors, and developing a network—that will lead them from the classroom to careers of influence.

“Many young women think that people walk around with tags on them that say, ‘I’ll be your mentor.’ I help them empower themselves to say, ‘Hey, I like that teacher. … I’m going to make an appointment and ask that teacher to mentor me … and to give me advice and to help me as my career proceeds,” she told CNN.

In the 2015 Fordham Magazine interview, she added another piece of advice she often shared with young people: “Don’t be shy,” she said. “Do. Not. Be. Shy.”

Robles-Román is survived by her husband, Nelson; their two children, Ariana and Andrés; four sisters; and four nieces and nephews.

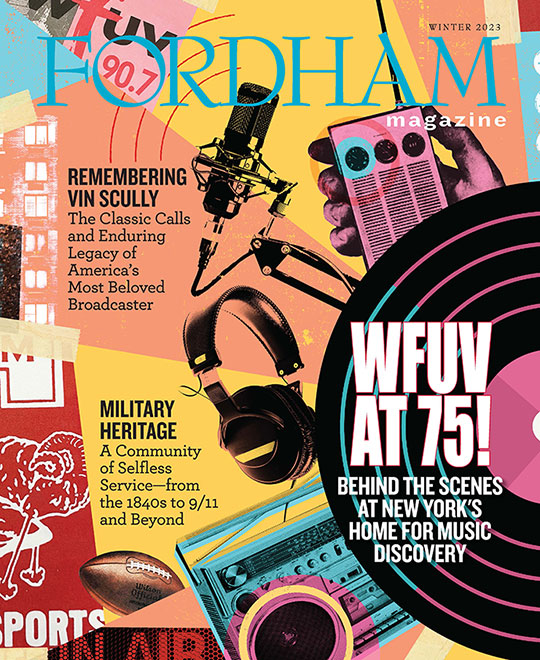

]]> The cover of the winter 2023 issue of Fordham Magazine has earned a UCDA Design Award of Excellence from the University & College Designers Association.

The cover of the winter 2023 issue of Fordham Magazine has earned a UCDA Design Award of Excellence from the University & College Designers Association.

To illustrate the cover story—“WFUV at 75: Behind the Scenes at New York’s Home for Music Discovery”—the magazine’s creative director, Ruth Feldman, turned to artist Tim Robinson, a fan of Fordham’s public media station whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications.

Like WFUV itself, Robinson’s illustration incorporates retro, classic elements in a vibrant collage. He created several other collages for the story, written by Kelly Prinz, FCRH ’15. Taken together, Prinz’s words and Robinson’s illustrations highlight how Fordham’s public media station connects an impressive legacy with an increasingly national reputation as a multimedia training ground and home for music discovery.

The UCDA Design Awards, established in 1971, recognize exceptional design and creative work done by communication professionals to promote educational institutions. Fordham Magazine will be featured among 145 other award winners at the 2023 UCDA Design Conference in Atlanta, Georgia, this fall.

]]>Enter the lowland rainforests of Malaysian Borneo, and you realize they are teeming with life, says Michael Patrick Davidson: orangutans, reptiles, amphibians, insects, brightly colored kingfishers and hornbills, tarsiers and long-tailed macaques.

“You can hear the symphony and cacophony of sound, as if you could and should be able to reach out and touch the creatures making those sounds. And yet it’s extremely difficult to see the creatures that are making those noises. You have to be patient, still, quiet, and keep looking,” he says. “Perhaps akin to God. You must have faith. You may witness the evidence of God in your life, yet you often must calm your mind, heart, and soul to feel and truly embrace that presence in your life.”

In the past 25 years, Davidson, a 1994 Fordham College at Rose Hill graduate and longtime member of the Fordham President’s Council, has traveled to 50 countries—in part through his work as a consultant, keynote speaker, and managing director at firms including Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and most recently JPMorgan Chase, where he was responsible for leading global corporate workplace operations, business transformation programs, and people strategies.

He’s also a wildlife photographer with a deep, abiding interest in conservation issues. Last summer, he traveled from New York to Southeast Asia to document the biodiversity of places—on Borneo, Komodo, and Sulawesi—that are increasingly threatened by habitat loss.

“Like so many people around the world, I was reading the headlines … about what was happening to the environment, to the rainforest, and to the orangutans,” he says in Through the Looking Glass, a documentary film he wrote and directed in September.

Borneo’s forests—home to more than 15,000 known species of flowering plants, 3,000 species of trees, 200 species of terrestrial mammals, and 400 species of birds—are thought to be 130 million years old. That’s twice the estimated age of the Amazon, Davidson notes, and yet “in the span of only 50 to 100 years,” those forests have been reduced by more than 50%, critically endangering orangutans, threatening Bornean elephants, and leaving other species vulnerable to extinction.

“One of the primary drivers for this deforestation is the palm oil industry,” he says. “Rainforests are clear-cut, all the layers of biodiversity are removed, and palm oil trees are planted. It provides a whole host of products that we like to use, we like to eat,” from shampoo and cosmetics to cookies and ice cream.

By making the documentary—which features photos, video vignettes, and forest sounds recorded on location—Davidson has added his voice to what he calls “a growing chorus” of people raising awareness of the effects of deforestation and human-caused climate change.

“We have a responsibility in how we consume, in how we live our lives,” he says, “that translates to what happens thousands of miles away.”

Honoring the Legacy of a Jesuit Brother

Growing up in New York during the 1970s and ’80s, Davidson says his earliest impressions of Southeast Asia as a boy were shaped by one-sided depictions in what was then mainstream entertainment. Reruns of films such as King Kong (1933), for example, with its fictional Skull Island, “didn’t do a great service to the image of Indigenous peoples,” he notes.

As a Fordham undergraduate, however, Davidson met a Jesuit who helped him develop a broader perspective on a distant corner of the world.

John J. Walter, S.J., had spent decades on Chuuk (formerly Truk), one of the Federated States of Micronesia. Beginning in the late 1940s, Brother Walter worked alongside the Indigenous islanders there to build Catholic churches and schools, including Xavier High School, which opened in 1952. A 1961 article in The Monitor, the official paper of the Archdiocese of San Francisco, described him as a “bearded Jesuit from upstate New York,” a skilled carpenter, handy with “hammer, saw, and T-square,” and a musician who played guitar and accordion.

“When I met him in 1992, I was a junior at Rose Hill,” Davidson says, “and it was by chance that I was assigned to him as the elder Jesuit to visit” as a volunteer at Murray-Weigel Hall, the Jesuits’ health care community in the Bronx.

“He had had at least one stroke that left him in a wheelchair, unable to speak words or sentences, but he had photo albums meticulously organized with typed captions for each photo through the years,” Davidson recalls. “This was how he introduced himself to me, and his inner personality and energy … shined through.”

Last summer, as Davidson planned to document his experiences in Southeast Asia, he recalled the work of his friend Brother Walter, who died in 1995, and he wanted to develop a project to honor the Jesuit’s legacy of service. “He was a pretty incredible person,” Davidson says.

‘The Greatest Gift’

Davidson arrived on the Indonesian island of Komodo on August 3 after a nearly 40-hour journey. For the next four weeks, every day was “filled with traveling, trekking, or exploring of some kind” from 5 a.m. to 8 p.m., he wrote in the preface to the collection of photos he published in September. He spent the majority of his waking and sleeping hours “deep in rainforests alone with a guide,” he wrote, “immersed in vines, branches, climbing up and down hills shrouded in dense foliage, over fallen trees and boulders, rushing streams, into mangroves, along remote beaches, amid extreme humidity, relentless heat and capricious rainstorms.”

In the book and documentary film that Davidson produced, he pays tribute to the people he met “who took care of me, who looked after me, who guided me, who were absolutely gracious hosts,” including a woman who let him and his guide take shelter under the roof of her house during a storm. “I think that’s probably the greatest takeaway, the greatest gift I have from this trip,” he says in the film.

‘Through the Looking Glass’

Davidson adopted the title of his film from the novel Lewis Carroll wrote as a follow-up to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, young Alice goes through a mirror to find a world where everything, including logic, is reversed. For Davidson, the title is a call to reverse the logic of unrestrained growth that fueled the past two centuries.

“Perhaps in the 19th and 20th centuries, progress was clearing land to build buildings, homes, to support a burgeoning population,” he says. “Maybe in the 21st century, progress is not that, but it’s about how we restore green spaces that were overdeveloped.” He adds that amid “a crescendo of climate change globally,” it’s time to “gaze through the looking glass at the world we will leave for future generations and bravely acknowledge the many aspects of our lives we need to reverse now to truly make the progress necessary to save that which will survive tomorrow.”

Watch the film:

]]>