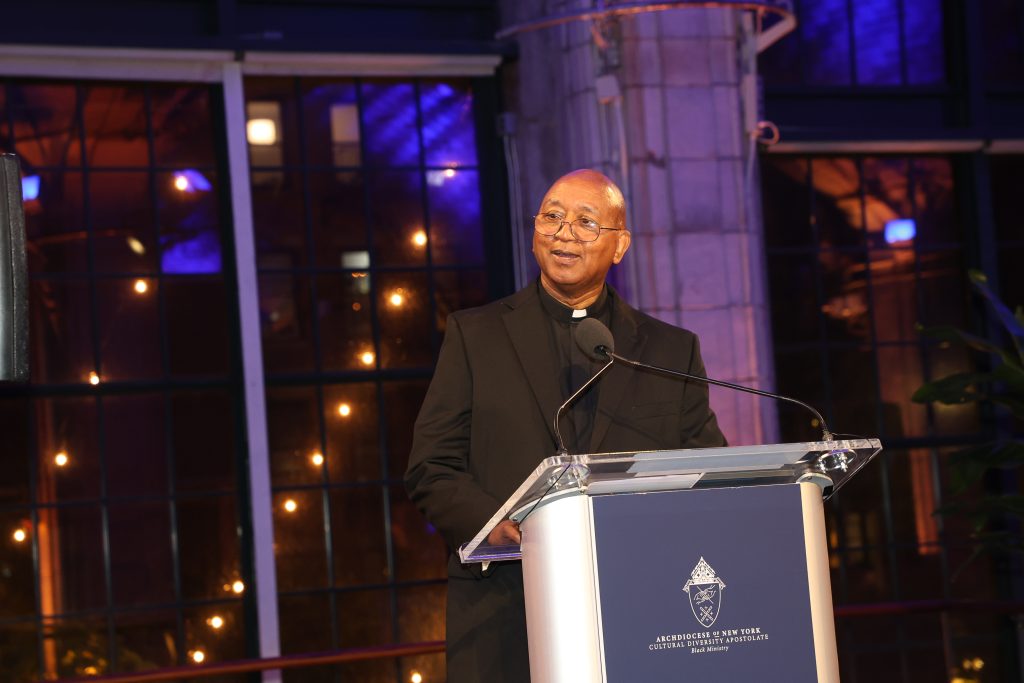

Hosted by the Archdiocese of New York’s Office of Black Ministry, led by Br. Tyrone A. Davis, C.F.C., the awards dinner recognized President Tania Tetlow and two Fordham scholars for their leadership and commitment to their communities.

The annual event supports the Pierre Toussaint Scholarship Fund, named for the once-enslaved Haitian-American entrepreneur who devoted his life to charitable work. Hundreds of attendees gathered in the landmarked Manhattan restaurant Guastavino’s to honor the scholarship recipients and this year’s Pierre Toussaint Medallion awardees, Grammy-winning saxophonist Kirk Whalum and President Tetlow.

Tetlow spoke about the inspirational life of Toussaint, who was emancipated in 1800s New York.

“As we think about leadership and how to lead with love, we remember the example of a man who escaped such profound pain and injustice and oppression. It would’ve been very human of him to lean into hatred and resentment,” she said. “And instead … he came to this city and was so incredibly generous … if we can, any of us, have a fraction of what he achieved every day, the world will be a better place.”

‘Service Is Love’

Two of the three Pierre Toussaint Scholars featured at the event were Fordham students: Angel Madera Santana, a Fordham junior studying English and pre-law (and the executive vice president of communications and marketing for Rose Hill’s United Student Government), and Fordham senior Joseph Giraldi, who plans to apply his engineering physics degree toward designing medical devices for patients in need.

Emcee Rev. Kareem R. Smith, a pastor of St. Michael the Archangel Parish in the Bronx and the senior chaplain for the scholars program, asked the students about its impact on their education.

For Giraldi, it “helped us become leaders in the sense that we view everyone with worth and we understand that we have a duty to serve,” he said.

Madera Santana said the program inspired him to serve others: “Service is love, and if we all share just a little bit of what we have, of our gifts and our talents, we would see the greater impact that love has on our community.”

Established in 1983, the Pierre Toussaint fund provides mentorship as well as spiritual and financial support to students of diverse backgrounds from public, private, and parochial schools throughout the Archdiocese of New York. Of the 88 current Pierre Toussaint Scholars across 45 universities, five of them attend Fordham, including sophomores Erika Grullon and Carol Riaz, first-year student Sofia Morales, and Madera Santana and Giraldi.

Pierre Toussaint is considered by many to be the father of Catholic Charities in New York. A hairdresser to well-heeled clients like Eliza Hamilton, he donated and raised money to open the first Catholic orphanage in New York and the original St. Patrick’s Cathedral, began the city’s first school for Black children, and cared for the sick. Pope John Paul II proclaimed him “venerable” in 1997, moving him further along the path to sainthood.

Before welcoming Cardinal Dolan and the Medallion awardees to the stage, the Executive Director of the Archdiocese of New York’s Office of Black Ministry, Br. Tyrone A. Davis, C.F.C., recognized the Black Catholic church leaders in the room.

A University Worthy of Toussaint Scholars

Archbishop of New York Timothy Michael Cardinal Dolan awarded Tetlow the Pierre Toussaint Medallion, recognizing her commitment to academic excellence, social justice, and service to young leaders.

“I am honored to accept this award on behalf of Fordham University,” she said, “which has for 183 years brought together brilliant faculty, like Bryan Massingale, and an incredible staff and administration, to create a university worthy of the student scholars that you got to hear speak tonight.”

In her remarks, Tetlow celebrated Fordham’s strides in increasing diversity against steep odds. “In this year when the Supreme Court banned us from considering race in admissions, our students of color went up to 50%,” she said to applause.

Cardinal Dolan then awarded the second Medallion to Kirk Whalum, who punctuated his thanks with a performance of the Whitney Houston song he famously soloed on, “I Will Always Love You.”

As the evening came to an end, Cardinal Dolan told attendees that more and more students come up to him now and say they are former Toussaint scholars. “And that brings such satisfaction and joy and gratitude to my heart … We couldn’t do it without folks like you.”

]]>Read the first page of Nancy McCann Vericker’s story and it becomes clear why it was difficult for her to write.

It begins in February 2008 with her then-19-year-old son, J.P. Vericker, being handcuffed by police outside their suburban New York home, high on drugs and ensnared in an addiction that made him desperate and sometimes violent. His hand was broken from punching a wall in a rage the day before.

It was not the first time the police had responded to the Verickers’ home because of trouble with their son. As officers restrained J.P. by holding him against the side of the house, an officer gently posed a question. The police department would keep responding as needed, of course, but “at some point, you have got to do something.”

“We have enough on him to arrest him,” the officer said. “What do you want to do?”

And, just like that, the Verickers were face-to-face with a decision they had seen coming but deeply hoped to avoid.

Nancy recounts this story in Unchained: Our Family’s Addiction Mess is Our Message (Clear Faith Publishing, 2018), which she co-authored with J.P., now eight years sober. It relates not only the course of J.P.’s addiction but also its impact on his family, and the spirituality that was a lifeline for both Nancy and her son. “I really did, honestly, feel this sense of calling” in co-authoring the book, says Nancy, a spiritual director and youth minister and a 2009 alumna of Fordham’s Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education.

In it, she charts her journey to accepting a seeming paradox, one that ran against her every instinct as a parent. To help J.P., she had to stop trying to rescue him. As she puts it in the book, “You must surrender to win. You must let go to get your loved one back.”

“My Manzo”

The second-oldest of the Verickers’ four children, J.P. wanted for nothing when he was growing up in their tight-knit family. He was a charming, kind, energetic child known to his mother as her little man, “my Manzo.” When the Verickers brought their adopted daughter, 2-year-old Grace, from China to their Westchester County home, J.P. was the first to quell her tears and make her laugh.

Things changed in eighth grade. He struggled in school and felt listless and depressed, and fell in with a partying crowd during his first year of high school. By sophomore year, he was drinking and smoking pot daily. He grew belligerent, cutting class and staying out past his curfew and getting into trouble with the police.

His parents saw a series of counselors and psychiatrists, looking for answers. They unsuccessfully tried to help J.P. by sending him to a wilderness program and a boarding school. Then, in senior year, he dropped out of their local public high school and started using cocaine and Xanax, sometimes together, a toxic combination that put him in a “manic state,” as he puts it. Mixing a stimulant and sedative, he writes, “can easily kill you.”

His parents saw a series of counselors and psychiatrists, looking for answers. They unsuccessfully tried to help J.P. by sending him to a wilderness program and a boarding school. Then, in senior year, he dropped out of their local public high school and started using cocaine and Xanax, sometimes together, a toxic combination that put him in a “manic state,” as he puts it. Mixing a stimulant and sedative, he writes, “can easily kill you.”

Family life moved forward in other ways—the Verickers’ eldest daughter, Annie, was in college and enjoying it; their next-youngest daughter, Molly, was a high-school freshman, making friends and playing field hockey; and Grace was doing well in her new elementary school.

But Nancy’s life was mostly consumed with J.P.’s addiction. Grappling with insomnia and worry, she realized he was stealing from her to pay for drugs. Bitter confrontations ensued, and in February 2008, in a rage, J.P. accosted his parents at home because of money he thought he was owed.

At the end of their rope, Nancy and Joe Vericker moved forward with the option they had been dreading, the one they had warned their son about: They decided to press charges of harassment. As Nancy stood by, distraught, Joe quietly gave permission to one of the officers who had responded to their home: “You can arrest our son.”

Tough Love

In order for J.P. to overcome his addiction, he had to suffer its consequences, she and her husband were told by the treatment professionals they consulted. He had to hit bottom, and they had to let him, counter to their every parental instinct. In addition to letting him be arrested, they had to refrain from rescue efforts like providing shelter and meeting his expenses as he continued to use.

After J.P. was arrested, his parents got a court order of protection and told him to stay away from the family’s home unless he agreed to seek treatment. Viewing it as a vacation, J.P. agreed to go to a treatment center in south Florida, chosen by his parents because of the wealth of post-treatment options in that area.

His story entered a new phase: detoxifications, relapses, halfway houses, flophouses, and homelessness. He struggled toward the realization that he needed help. Today, he has a clear view of his warped thinking from that time.

“Being addicted is like having rabies,” he writes in Unchained, which includes first-person accounts by both him and his mother. “To me, in my addicted mind, my life was normal,” and others were to blame for the strife and altercations in his life.

In lucid moments, he felt a deep yearning to stop using. During a brief trip home from Florida, he broke down in tears for two hours, “flooded with both anger and sadness,” he writes. “I was starting to realize I could not stop on my own.”

Nancy, meanwhile, alternated between hope when he seemed to be recovering and anguish, tears, and sleepless nights when he relapsed. She often didn’t know where he was or what he was doing.

And yet, life went on. Family responsibilities beckoned. She gained solace and strength from family, friends, and community, but also from her degree program at Fordham.

Ignatian Lessons

A former journalist, Nancy Vericker first enrolled at Fordham at the suggestion of her spiritual director during a time when she was tending to the children at home, doing occasional volunteer work, and spiritually searching. She spent more than a decade earning a master’s degree, and the studies would help pull her through difficult times—in part, because of the Ignatian teachings in the curriculum.

“There was this thing that was oppressively suffocating the life out of me and my family, and Ignatian spirituality helped me push back,” she says.

In keeping with the Ignatian view of the soul as a battleground, she fought against feelings of desolation—depression, fear, anxiety—by finding consolation in the joys of family life and moments of grace, holding on to those as a way of building generosity of heart and fueling hope.

“Ignatian spirituality saved me in many ways,” she says.

What also helped her were the relationships built up during the program. When J.P. was homeless, she considered quitting, but she persisted with encouragement from a classmate, Mark Mossa, S.J., who went on to become campus ministry director at Spring Hill College in Alabama.

And she became close to Janet Ruffing, R.S.M., then head of the spiritual direction program. When graduation day came for Nancy, she decided to instead go to her daughter Grace’s First Communion, which fell on the same day.

“I knew how torn she was, having made that choice,” says Sister Ruffing, now a professor at Yale Divinity School. “She was consistently making those kinds of choices for her family.”

So Sister Ruffing drove to the Verickers’ home and brought her the degree, entering the house in the midst of a post-Communion party. “They all screamed,” she says with a laugh. “I just felt she deserved to get her degree on graduation day.”

It was a powerful gesture, Nancy says, because she was in despair at the time. She had her doubts that J.P. would survive.

Refusing him help was painful. During one Christmas season, J.P. was calling home over and over from Florida, saying he was homeless and hungry, asking for money. “You cannot under any circumstances send him money,” J.P.’s treatment program director said. He told the story of a woman who, faced with a similar plea, wired money to her addict son, who then spent it on drugs and died of an overdose.

The Verickers kept saying “no,” even on Christmas Day, a few days after J.P.’s 21st birthday. “We will help you when you are ready to get help for your addiction,” Joe Vericker told J.P. on the phone. “We love you, remember that.”

Recovery

J.P.’s recovery began in a low moment, just after he had been jailed in Florida. “I was fearful for my life if I went on using,” he writes. He surrendered his false pride, his sense that “I knew all the answers,” and reentered treatment and joined a 12-step program.

For many addicts, he says, recovery is like dragging rocks in the beginning because they’re physically wrecked, their lives are in ruins, and drugs offer instant relief from the physical agonies of withdrawal. “Their mind is under the impression that they need [drugs]to survive,” he says.

He overcame these obstacles through meditation, help from a support network, and prayer—a crucial defense in the moments when his addiction was banging at the door.

“It was like alarms were going off,” he says. “I was scared that I was going to be, like, possessed and just pick up drugs and use them, because it felt like what had happened sometimes.” He would instantly stop and pray, over and over, “God, please remove the obsession.”

The stark choice he faced in those days has stayed with him. Any passing temptations to accept a drink are quickly quashed by one simple thought: “I don’t want to die.”

The spirituality of his Catholic upbringing helped him stay centered and clean as he earned a GED diploma and a bachelor’s degree in addiction studies, and enrolled in an M.B.A. program. In his mother, he had someone who could relate to his struggle; nearly three decades ago, she had to overcome her own addiction to alcohol.

“The twelve steps are a bond I love having with my son,” she writes. She and J.P. don’t act as each other’s sponsor, the person who “takes you through the steps and offers guidance based on their own experience, strength, and hope in the program.” But they do “share a love of the fellowship,” she says, “and we can give each other advice—as a mother and son would to each other.”

Today, as a board-certified substance abuse counselor and co-founder of the outpatient Northeast Addictions Treatment Center in Quincy, Massachusetts, J.P. spends his days overseeing the center’s operation and counseling people addicted to opioids that are far more deadly than the drugs he was using. And, since the publication of Unchained, he has joined his mother in spreading the book’s message of hope and recovery and trying to reduce the stigma addicts face.

They shared that message on NBC’s Today show and on the SiriuxXM radio/television show Conversation with Cardinal Dolan, among other programs. Their story has spread through word-of-mouth, and some mothers have contacted her to say “I felt like I was reading my own story,” Nancy says.

“I get up every morning and try to think of ways to get this story out there. It’s just to let people know that help is available. I will answer every email, we’ll talk on the phone, I’ll call people back,” she says, “because I feel like this is part of what I’m supposed to be doing with my life right now.”

First stop: The Medieval and Byzantine Art Galleries, where modern couture mingled with the Met’s permanent collection.

So, what do you think?

Wow. I’m really stunned and I didn’t expect to be. Frankly, they’ve just exploded it, and looked at Catholicism with new eyes. It makes you look at the Catholic liturgy and vestments in a new way. I didn’t realize until we got here how much this is really an outreach to Catholics, at whatever level of their participation in the Church, as much as it is to the rest of the world. It’s this great osmosis between the secular and the sacred where it’s taking something sacred, advancing it creatively and artistically, and maybe the sacred could take that and again let it re-inform our own liturgical practices.

Most of these designers grew up in European countries where the church is part of the culture. Would you say it’s just a matter of course that the church is part of their visual language?

Yes, they’re always informed by it. I don’t want to be too tough on Americans, but we tend to reject our traditions and disassemble them. I think Europeans, even Catholics who have a certain distance from the church, are still able to use Catholic culture, which is so dense and pervasive there, and reappropriate it in their art. From Fellini and his film Roma, which they site here in the exhibit, to Paolo Sorrentino, the creator of The Young Pope on HBO, they all draw on Catholicism for inspiration. Some, however, would say it’s not done properly, that it’s not reverent enough.

Is the Vatican’s loan of objects from the sacristy of the Sistine Chapel a kind of proselytization?

I wouldn’t call it proselytizing. Pope Francis says you should be drawn to faith by attraction. We do not proselytize. We draw by attraction, so in that sense the exhibit, so far, it’s pretty successful—at least for me!

Downstairs, in the Anna Wintour Costume Center, papal vestments and jewel encrusted crowns, on loan from the Vatican, are reverentially separated from the couture pieces.

There will likely be a lot of commentary about the riches of the church on view here and whether the church should just sell it all off and give to the poor. Why does the church hold on to such valuable treasures?

I think that’s one of the weaker, even lazier arguments, that you often hear and this exhibit is a powerful refutation of that. The Catholic Church has these treasures which celebrate a broader tradition rather than just Catholic tradition. It’s also a Christian and Western tradition. By lending these items out and collaborating as the church does, and the Vatican museums do, it shows why it’s critical to keep this sort of thing together in a collection that’s accessible and open to people. But not just people who can afford to go to Rome, or afford to pay for the museum. It is our patrimony, and we’re sharing this with the wider world. I mean, do you want to go sell the Vatican’s great works of art and have them sit in private collections where nobody will ever see them again? No, you want to keep them and you want to lend them out.

Pope Francis has eschewed the grand style we see on display here, right down to the simple wooden cross that he wears. Is there a contradicting message with the Vatican’s loan?

It is odd to see this at a time when we’re celebrating this very dressed-down Pope Francis. This exhibit celebrates an old-fashioned high church style, and one that opens up a lot of other questions: Where does this exhibit connect? Is it terribly, wonderfully, European? I traveled with John Paul II and in Swaziland I saw him wearing a leopard skin pelt, literally a real fur, as a vestment over a chasuble as he came out to celebrate an outdoor Mass. You don’t see anything like that here.

They have a vestment by Matisse on loan from MoMA, which seems to be the one of the few modernist pieces of from the Church side of the show. Most look like they are from the 19th century.

There’s a timelessness to those. Those 19th-century mitres and tiaras could have been worn a thousand years earlier, and fit right in. But, if you were to wear them today, people would say, like they did with Benedict XVI, what the heck are you doing?

So, is it true that the clothes make the man, even for the pope?

I mean, that’s part of the genius of Catholicism – that you can elect an austere, simple-living cardinal from behind the Iron Curtain, who becomes the first Polish pope. He puts on the white soutane, and he becomes Christ’s vicar on Earth. He becomes the pope. Same with John XXIII. He described himself as an Italian peasant, and he loved to eat. He was so overweight they didn’t even have a white soutane big enough for him when he was elected. But again, he puts that cassock on, and all of a sudden, this heavyset old fellow from a small village in northern Italy, becomes the pope. That says a lot about the power of classic, timeless clothing and the power of Catholic traditions and the Catholic sensibility. Any man who becomes pope becomes a kind of a noblility, at least spiritually speaking, in part because of the uniform he wears.

A film star. A man whose life inspired a movie. A groundbreaking African-American dean. An Olympic champion. Recipients of the Medal of Honor and the Medal of Freedom.

“These are our heroes,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham.

Father McShane was reflecting on the latest Hall of Honor inductees, who were celebrated at reception following a Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Oct. 1.

It was a heady evening, which saw well over a dozen members of the Fordham family inducted into the Hall of Honor, the Magis Society—and one very singular Founder’s Award going to His Eminence Timothy Cardinal Dolan.

In addition, the Mass also represented the fall opening celebration of the University’s Dodransbicentennial year.

“We present these honorees to the world as examples of what a Fordham education produces: men and women of exceptional talent who have pursued excellence in all they did, and who have devoted their lives to the service of others,” said Father McShane.

At the cathedral Cardinal Dolan celebrated the “grand marriage” of faith and reason, represented by the education many have received at Fordham. He said that, back in 1841 Fordham founder Archbishop John Hughes fully understood that Catholic education would provide the “intellectual wattage” needed in the then-young city.

Cardinal Dolan also said that knowledge obtained at the University, whether in philosophy, theology, math, chemistry, business, art, literature, or science, “speaks in some way of Jesus the word made flesh.”

At the reception held at the University Club following Mass, Fordham launched the brand new Magis Society. The society recognizes individuals and groups whose support to the University exceeds $15 million. The inaugural class included: Stephen E. Bepler, FCRH ’64; Kim B. Bepler; Maurice J. Cunniffe, FCRH ’54; Caroline Dursi Cunniffe, Ph.D., GSAS ’71; Mario J. Gabelli, GABELLI ’65; Regina M. Pitaro, FCRH ’76; Thomas A. Moore, LAW ’72, PAR ’15; Judith Livingston Moore, PAR ’15; the Jesuits of Fordham; the McKeon Family; and the Walsh Family.

A few guests noted that having the reception at the club, once solely the province of Ivy League universities, is yet another reminder of how far Fordham has come. And when film actress and honoree Patricia Clarkson, FCLC ’82, entered in a blue gown it brought its own brand of sparkle to that august institution as well.

In accepting her Hall of Honor award, Clarkson said a Fordham education had carried her through her 31-year acting career. She grew emotional when recalling her acting professor, Joseph Jezewski, who she said was the first to tell her that her “talent was limitless” and taught her how to live a “true artistic life,” which had little to do with fame and all to do with “love, passion, compassion, and truth.” Clarkson is the winner of two Emmy Awards and has been nominated for an Academy Award.

“I don’t need an academy award; I’m in your Hall of Honor,” she said.

Clarkson set the emotional tone for other acceptance speeches, which were largely delivered by family members of Fordham alumni who had passed away, including the daughter of honoree James B. Donovan, FCRH ’37. Donovan, a lawyer and naval officer, was the protagonist of the recent Steven Spielberg film, Bridge of Spies.

Mary Ellen Donovan Fuller said her dad loved to hang out with the Jesuits at Rose Hill because “everybody knew the Jesuits were the intelligentsia, and dad loved that.”

J. Donald Dumpson, nephew of honoree James R. Dumpson, the former dean of the Graduate School of Social Service and first black commissioner of the New York City Department of Welfare, said that his uncle taught him how to “dream big” and how to “love those you don’t know.”

The extraordinary valor of two World War II heroes, honorees John Fidelis Hurley, S.J., FCRH 1914, and Thomas J. Kelly, UGE ’56, LAW ’62, brought gravitas to the room. Father Hurley received the Medal of Freedom from General Douglas MacArthur for his work in Philippine internment camps, where he more than once risked his life to ease the suffering of others. Kelly was awarded the Medal of Honor for rescuing 17 men on a battlefield in Germany.

John J. F. Mulcahy, Sr., of St. John’s Class of 1894, rounded out the list of honorees. He was the founder of Fordham’s rowing club, and winner of the gold and silver medals at the 1904 Olympics. Despite being active on campus well over a century ago, Mulcahy, like all the inductees, should serve as an inspiration to today’s students, said Father McShane.

“We hold these men and women up to our students to say: Here are your older sisters and brothers who have done great things. Extraordinary things. Emulate them.”

This weekend, Fordham will be the site of the inaugural New York Catholic Men’s Conference, a new initiative from the Archdiocese of New York.

This weekend, Fordham will be the site of the inaugural New York Catholic Men’s Conference, a new initiative from the Archdiocese of New York.

The daylong conference, which promises to draw more than 500 men from New York City, Staten Island, and upstate New York, is cosponsored by the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education.

New York Catholic Men’s Conference

Saturday, March 21

7 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Rose Hill Campus | Fordham University

Bronx, NY

Themed “Men, Be Who You Are!”, the conference will provide an opportunity for men throughout the Archdiocese to examine their spiritual lives. The goal is to help men cultivate a personal spirituality by encouraging participation in Church sacraments and promoting an active prayer life.

Speakers include:

- Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, Archbishop of New York

- Joe Kleck, former New York Jets defensive lineman

- Damon Owens, executive director and lecturer at the Theology of the Body Institute

Read more on the conference website.

For more information about attending, contact Kim Quatela at 646-794-3198, or by email.

]]>Sarah Weber, GSAS ’05, received the 2015 Swanstrom-Baerwald Award for Excellence during a special ceremony held at in Rose Hill’s Keating Hall. The biennial award—of which Weber is only the fourth recipient—recognizes members of the Fordham community who demonstrate stellar commitment to the service of faith and the promotion of international peace and justice.

Weber, a graduate of Fordham’s International Political Economy and Development (IPED) program, was honored for her work at Catholic Relief Services (CRS) in support of the Global Fund for AIDS, TB, and malaria. Her work to secure three grants totaling more than $65 million has helped to distribute 450 million insecticide-treated mosquito nets in Africa to protect families against malaria.

Her service with the Global Fund is just the most recent instance of her international development career, which spans close to 20 years. She received a Fulbright Fellowship to Botswana after graduating from Sarah Lawrence College in 1997; served with the Peace Corps in Côte d’Ivoire; conducted a microfinance internship in Mali while in the IPED program; and has worked with CRS in Ghana, in post-conflict Liberia, and in Benin.

“You have to be an optimist if you want to stay in the field of international development for the long haul,” Weber told an audience of dignitaries, students, peers, and her former teachers.

She said one of the challenges of humanitarian work is “investing everything you have” into a project with no way of knowing whether you’ll get the results you’d hoped for.

“You want to do the right thing, and the people you’re working with want to do the right thing,” she said. “But when it comes to actually making that thing happen, you don’t always know if it’s going to work.”

Photo by Dana Maxson

Weber works at CRS’ headquarters in Baltimore, providing technical support to CRS country teams around the world that are furthering public health.

Joining the ceremony were: Joseph M. McShane, SJ, president of Fordham; Archbishop Bernadito Auza, the Apostolic Nuncio and permanent observer of the Holy See to the United Nations; Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, the Archbishop of New York; and Michelle Broemmelsiek, executive vice president of CRS for overseas operations.

At a dinner following the award ceremony the Father John F. Hurley, SJ Commendation was presented to Irene Baldwin, FCRH ’83, for her work in support of CRS. Also recognized were two travel fellows—Elvin Rivera and James Sheridan, both of St. Joseph’s Seminary of the Archdiocese of New York.

The Swanstrom-Baerwald Award honors the memory of Friedrich Baerwald, PhD, former professor of economics, and Bishop Edward E. Swanstrom, FCRH ’24, GSAS ’38, a student of Baerwald’s and the founder of CRS.

]]> On Wednesday, Dec. 3, His Eminence Timothy Michael Cardinal Dolan congratulated and blessed two Fordham graduate students who have been assigned to work with Catholic Relief Services in Africa. From left to right are : Sean Kenney, Cardinal Dolan, and John Mulqueen. The students are students in Fordham’s International Political Economy and Development program.

— Janet Sassi

]]>

On Wednesday, Dec. 3, His Eminence Timothy Michael Cardinal Dolan congratulated and blessed two Fordham graduate students who have been assigned to work with Catholic Relief Services in Africa. From left to right are : Sean Kenney, Cardinal Dolan, and John Mulqueen. The students are students in Fordham’s International Political Economy and Development program.

— Janet Sassi

]]>It was equal parts pep rally, comedy show, and religious revival in the Rose Hill Gymnasium on Friday evening, Sept. 14, when Timothy Cardinal Dolan, archbishop of New York, joined Stephen Colbert, host of Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report, for “The Cardinal and Colbert: Humor, Joy, and the Spiritual Life.” The discussion—moderated by James Martin, S.J., author of the book Between Heaven and Mirth (HarperOne, 2011)—drew a rousing crowd of more than 3,000 spectators, mostly students, prompting The New York Times to call it perhaps “the most successful Roman Catholic youth evangelization event since Pope John Paul II last appeared at World Youth Day.”

The conversation had more than its fair share of zingers—Dolan: “Do you feel pressure to be funny all the time?” Colbert: “Do you feel pressure to be holy all the time?”—but the theme that emerged was quite serious.

“Lord knows there are plenty of Good Fridays in our lives,” Cardinal Dolan said, “but they will not prevail. Easter will. As we Irish claim, ‘Life is all about loving, living, and laughing, not about hating, dying, and moaning.’”

One of the highlights of the evening was an animated cartoon created by Fordham College at Rose Hill senior Tim Luecke, a visual arts major and an honors student. The video, screened at the start of the event, shows the participants on campus, where Cardinal Dolan and Colbert get chased by the Ram, and Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, has the last laugh.

]]>